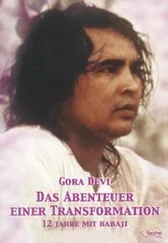

I am particularly moved by the music and the songs, by Babaji's splendour and the devotion of the Indian people. They stand in a long queue holding garlands of flowers in their hands as an offering, then place them around His neck before they pranam to Him and receive a gesture from Him, a smile, a word or some prasad, blessed food.

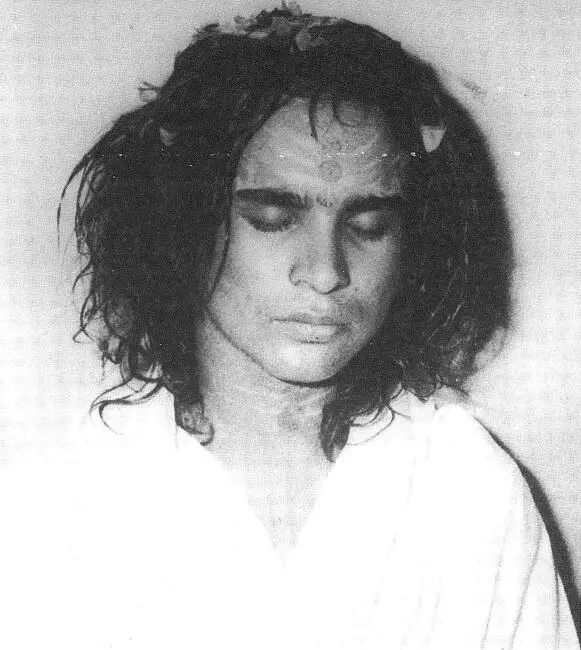

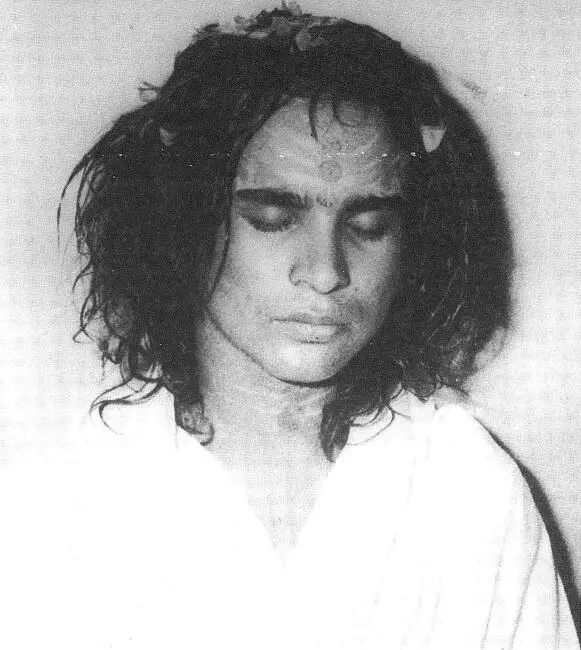

I also stand in line and I feel extremely emotional just by coming in close proximity to Him. An energy of great intensity emanates from Him and I experience an incredible sensation, sensing as well that He can read all my thoughts. His eyes are magnetic, shining, full of love, strength and knowledge. I never become tired of looking at Him and notice that everybody else does the same. For two or three hours Babaji continues to sit virtually motionless. He doesn't speak, doesn't do anything, He just makes Himself visible for us to contemplate and adore; He gives darshan, which Indian people explain to me as being a vision of the Divine in a human form.

The impact of this experience touches everybody in an intimate way; I can see it in people's eyes and from the energy in the temple. People sing continuously, sometimes Babaji's mantra, 'Om Namah Shivaya', sometimes other devotional songs, until late in the evening.

At night we sleep on the roof of a small building constructed next to the temple, lying on a straw mat, the place surrounded by monkeys. It is still dark when we are woken up at four o'clock in the morning as devotional chants begin resounding from all of the temples in the city, more than seven hundred of them. After a shower I meditate in a corner for a short while, then we go to the temple for the aarati, morning prayers. We wait with trepidation for Babaji's arrival, for Him to emerge from His room and be seated on the modest dais prepared for Him. The temple is extremely clean, full of flowers and smelling of sweet incense.

We don't have breakfast or dinner, only a large lunch, as well as pieces of halva and fruit that are distributed during the day. Some people continue singing until late in the morning, other people work, either cleaning, washing, cooking or carrying drinking water from the well that is situated in the square opposite the temple. Babaji often speaks with individual people, just a few words here and there, very quietly, softly. After lunch everybody has a short afternoon nap and at about five o'clock we bathe and meet again in the temple, in order to clean and prepare everything for the evening worship.

In the afternoon many people choose to go to the river to bathe, in the Jamuna, a river sacred to Lord Krishna. In the evening the aarati ceremony is performed again and afterwards people sing until late in the night, beautiful, sweet songs. I don't understand the meaning of the words, but I surrender to the melody, to the feeling of a divine dimension.

It's tremendously difficult for me to adjust to the daily routine and to the strict discipline, to the Indian capacity for hard work, particularly because the weather is extremely hot and it makes me feel tired. The month of May is torrid in India, an especially oppressive time of the year and I often escape to the bazaar to find something cool to drink, even if I know that Babaji doesn't approve of it.

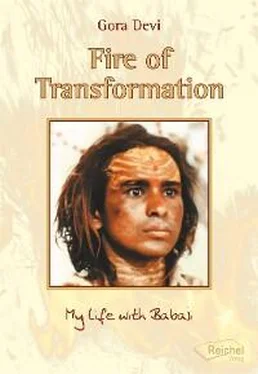

Babaji - '...dressed in white, always so beautiful, unreal, etheric, radiant.'

15 May 1972

I am beginning to find it difficult to withstand the way of life here. The daily routine is tiring, monotonous and some of the young Indian men are very brusque and treat me badly, they don't allow me to work with them and they treat me as if I am a stranger. Babaji always fascinates me, but even He keeps me at a distance, is unapproachable. It is almost impossible to communicate with anybody, since I don't know Hindi and can speak only a few words of English.

In this intense heat I always feel thirsty but the water from the well is tepid and a little salty; it does not quench my thirst. When I bathe in the river, which is cloudy and muddy, it leaves me with a strange sensation and I don't really feel clean after washing. In the morning I have to wait in a queue for an interminable length of time in order to be able to take a shower in the guesthouse. In the evening in the temple, everybody is sweating, the temperature rises to more than 40 degrees centigrade, it's sweltering but Babaji seems totally indifferent, not sweating Himself.

In Vrindavan there are hundreds of ageing widows all dressed in white saris, who live all together in various temples. They pray continuously, accompanied by the sound of small cymbals and other instruments. Some of the old women are extremely poor, their saris white-grey, and they ask for alms. It reminds me of a scene from Dante's Purgatory. People explain to me that in India a widow cannot marry a second time; she has to renounce the world, she loses her home, her possessions and spends the rest of her life in prayer. It seems extremely cruel to me and ironically I remember the women's liberation movement in the West. I start to feel restless and a strong sense of nostalgia arises in me to see my Western friends again in Delhi; I ask Babaji if I can go away for a while and He allows me to leave.

* * *

Delhi, 18 May 1972

I have started to travel around on my own without any fear or uneasiness. The other day, while waiting for a train in the railway station, I spread a piece of cotton on the platform like the Indians do and I sat down patiently to wait, using the time, as they do, to contemplate life and myself.

Railway stations are meeting places in India, joyful and familiar, and people talk to each other all the time. The Indian people regard me as a curiosity, they ask me where I come from, why I have come to India, what I am looking for. They are surprised that I have left the West, which in their minds is a paradise of material comforts, in order to come here and share their poverty. Some of them ask me if I am looking for mental peace, invite me into their homes, offer me food and shelter, all with a great sense of hospitality and humanity. In India to be hospitable is regarded as a sacred undertaking and people offer it with much warmth, their eyes gentle and full of love.

21 May 1972

I have been in Delhi for a few days and I feel comforted by the city. In old Delhi, in the Crown Hotel, I meet up with my friends again, Piero, Claudio, Shanti and some other people recently arrived from Italy. The hotel is on three floors, old and dirty, but rather grand in its way and from the terrace there's a commanding view of the railway terminus in the old part of the city. It's also the crossing place for numerous roads, the point of departure for numerous destinations, the location of many Hindu temples alongside Muslim mosques. It seems like the meeting place of different civilizations, India, Muslim countries, the West, China, and Tibet. Down on the streets there's a continual movement of people, rickshaws, horses, carriages, cows and cars, there seems no end to it all. Cows are regarded as holy and are shown great respect, so if they decide to cross the road the traffic comes to a standstill.

Many Westerners are camping out on the big terrace as well as occupying the small, hot, humid rooms where they keep the fans on all the time. As in Bombay, people smoke a lot and consume large quantities of fruit juices, tea and sweetmeats, taking numerous showers to fend off the heat. It's not a beautiful or a comfortable place, but it has a certain magical charm despite the dirt and chaos, not least because there are people here like me, searching for truth, ready to risk everything, to suffer, even to go so far as to lose themselves completely for the sake of this spiritual adventure.

Читать дальше