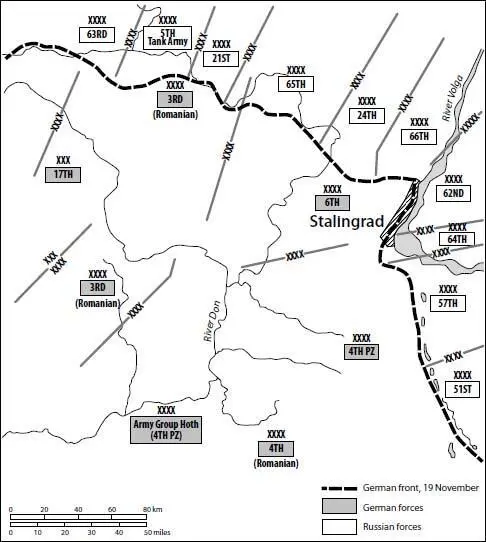

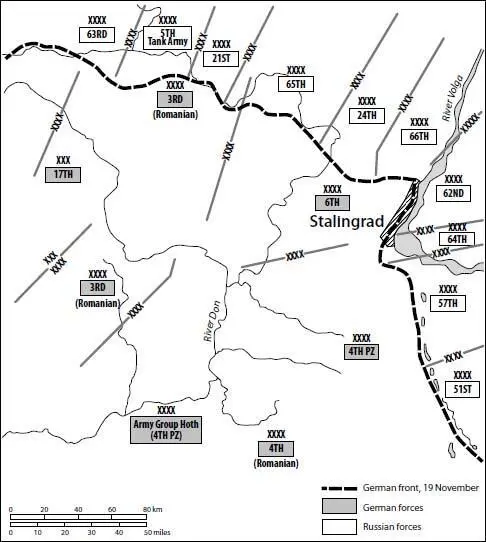

Map 2.1: The Stalingrad campaign, 1942

Source: Based on map from iMeowbot / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain.

The twentieth century seems to confirm Duffy’s thesis. From 1914 to 1991, a correlation between force numbers and urban warfare is observable. Urban warfare was the subordinate form of battle. The mass armies of this era were so large that they formed fronts that encompassed cities and urban areas. Sometimes, armies conducted urban battles, but, precisely because of their immense size, most major confrontations took place in the field where combatants could deploy their full combat power against each other.

Converging on Cities: Twenty-First-Century Warfare

The military situation is now quite different. Yet, the significance of reduced forces has barely been mentioned in the current literature on urban warfare. If Delbrück and Duffy are correct, though, then it is almost certain that the radical reduction in force sizes evident in the last few decades will have been significant. Clearly, in order to demonstrate the correlation between reduced combat densities and urban warfare, empirical exemplification is necessary. This is not easy. While civil wars have proliferated, there have been few interstate wars in this century, and even fewer between advanced powers. So, the evidence is sparser. Indeed, only two recent interstate wars have involved at least one global power whose forces have been equipped with advanced weaponry: the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and the ongoing war in the Donbas.

Neither example is perfect. The Americans fought a very weak Iraqi Army in 2003; it was a mismatch that lasted only three weeks. American forces enjoyed a freedom of manoeuvre that they would certainly not be accorded against a more equal rival. So great care needs to be taken in extrapolating from it. However, Operation Iraqi Freedom also has some methodological advantages. In particular, the invasion becomes particularly pertinent as a data point when it is compared to the 1991 Gulf War. The Donbas, of course, is not officially an interstate war at all; it is a civil war between the Ukrainian government and separatist militias. However, the involvement of Russia has been so pronounced that this conflict is better understood as a hybrid war between two states. So, while significant caution needs to be exercised when extrapolating from these wars, they offer at least some evidence for testing Duffy’s thesis.

Following Donald Rumsfeld’s imperatives about the ‘Afghan model’, the US-led coalition that invaded Iraq in 2003 was small. 42The total coalition force consisted of about 500,000 personnel, with 466,000 Americans, but the invasion force was much smaller – just 143,000 troops. 43The Land Component consisted of five divisions (four American and one British). The US forces advanced on Baghdad on two parallel axes: the 3rd Infantry Division in the west, the 1st Marine Division in the east. The other three divisions (101st Airborne, 82nd Airborne and 1 UK Divisions) played supporting roles, clearing and holding the lines of communication in the south.

The Iraqi Army was similarly diminished. In 2003, it consisted of 350,000 troops: twenty to twenty-three Regular divisions, six Republican Guards divisions and one Special Republican Guard division. 44Yet, most of these formations played no part in the invasion. The coalition eventually engaged a force of only four divisions, consisting of 12,000 Special Iraqi Republican Guards, 70,000 Republican Guards, supported by 15–25,000 Fedayeen fighters and a Special Security Service: around 112,000 in total. 45The Iraqi Army deployed in a highly unusual if not idiosyncratic manner. 46Much of Saddam’s force was positioned in the north or east against the Kurds and Iran. Saddam deployed his best Republican Guard and Special Republican Guard divisions to the south of Baghdad, with a view to defending the city in a series of blocking positions outside it. In the end, these divisions fought very poorly. They suffered disastrous desertions before they were even engaged and were easily targeted by US air forces once the war started. 47They participated in only one noteworthy encounter: the fight at al-Kaed Bridge (Objective Peach) on 2–3 April 2003, the ‘single largest battle against regular Iraqi forces’. 48In this engagement, a single US battalion – the 3rd Battalion, 69th Armor Regiment – defeated elements of the 10th Armoured Brigade of the Medina Division, the 22nd Brigade of the Nebuchadnezzar Division as well as Iraqi special forces in just three hours – without suffering a single casualty. 49Meanwhile, Saddam deployed only the Ba’ath Party and Fedayeen into his cities, primarily to shore up his own regime, though, in the end, they did much of the fighting.

The Americans were worried that Saddam would turn his cities into fortresses. 50Certainly, the scale of urban fighting would – and perhaps should – have been much greater in 2003 had Saddam deployed his heavy forces into his cities. For Stephen Biddle, ‘perhaps the most serious Iraqi shortcoming was the systematic failure to exploit the military potential terrain’. 51Indeed, Iraq officers were bizarrely opposed to urban fighting: ‘Why would anyone fight in a city?’ 52Yet, combat was still concentrated in urban areas. The battle of Al-Kaed Bridge, notwithstanding, most of the major engagements occurred in An Nasiriyah, An Najaf, Samawah and Baghdad. For instance, An Nasiriyah was the site of a major battle because two crucial bridges over the Euphrates River and a canal on Highway 7 were located there. The bridges were strategic choke points on the US line of advance. The Iraqi Army’s 11th Infantry Division, supported by Fedayeen fighters, put up a formidable defence in the city on 23 March 2003 against the US Marine Corps’ Task Force Tarawa. 53The battle was the single most costly action in the whole campaign for the US: eighteen US marines were killed in the course of the fighting. 54

In addition, 101st Airborne Division mounted a major assault to clear An Najaf, while 82nd Airborne secured Samawah. The two battles were the largest ground combat operations in which either formation was involved. Finally, although it had been involved in a number of engagements during its advance, the 3rd Infantry Division experienced its most intense challenge when it eventually reached Baghdad during its famous ‘thunder runs’ into the city. The 2003 Iraq invasion was a relatively urbanized campaign, then (see Map 2.2).

How is the scale of urban fighting during the invasion to be explained? Demography was plainly not irrelevant. An Nasiriyah, An Najaf, Samawah and Baghdad each had large populations, of respectively 300,000, 400,000, 200,000 and 5.6 million. 55Because the objective was Baghdad, the US forces had to advance through these urban areas in order to defeat the Iraqi Army and bring down the regime. It was, therefore, highly likely that there would be extensive urban fighting, especially since American weaponry was so devastating in the field. However, while demographics played a part, force numbers were very significant too. Yet, they have been overlooked. It is possible to rectify this neglect by thinking comparatively. Here, the influence of numbers on the distinctive geometry of the Iraq War can be illustrated most graphically by comparing the invasion of 2003 with the Gulf War of 1991. During the 1991 conflict, a US-led coalition sought to eject Saddam Hussain’s forces from Kuwait, which he had invaded in August 1990. After a massive build-up, the Gulf War began in early January 1991 and involved six weeks of coalition air bombardment before a four-day ground battle. The Iraqi Army suffered a crushing defeat in the deserts of southern Iraq and Kuwait. There were evident parallels between the two campaigns.

Читать дальше