Undernourishment and hardships would have resulted in the death of a far greater number of Jews even before Auschwitz, had it not been for the compassionate individuals among certain merchants. In their own ingenious ways, they sabotaged the policy of starvation and the practice of cold-blooded destruction of human life prescribed by the party and the government. Despite great dangers to themselves and extreme acts of reprisals, these helpers supplied those Jews with food who were disallowed from having any. The greatest danger derived from the following situation. Beginning in September of 1941, the wearing of the “Star of David” had become mandatory. Subsequently every policeman, as well as every civilian, could easily identify Jews on the streets. “Open your bags,” they would shout at us at every possible moment. It had become a strict policy by the Gestapo to request Jews to open their shopping bags and briefcases. Woe to those outcasts who were caught hiding something to which they were not entitled. Before being arrested, these Jews were forced to say precisely from where their groceries had come, whereas a compassionate merchant had to prepare for the worst. It was also disastrous if during one of the frequently conducted house searches something illegal items were found, such as food. If the Gestapo uncovered the sum of several hundred marks, a Jew was accused of being a racketeer and was lucky receiving only a light punishment.

The strangest aspect of this anti-Jewish policy was – with the exception of the Nuremberg Laws – that the so-called “Decrees against Jews” were published nowhere. Instead, new decrees were only announced at the central office of the former Jewish community, and from there they had to be publicized by word of mouth. Radios had been confiscated long before. We could neither subscribe to a newspaper nor could we buy one at the newsstand. Jews learned of a new decree only indirectly and in a round-about way, even though the decree could affect one’s very existence. Still, ignorance was an insufficient excuse for violating even the most ridiculous law. For example, violation of a traffic law would result in one’s immediate arrest by the Gestapo. This in turn meant one’s prompt deportation.

“Deportation!” This ominous word was like a nightmare that gradually affected both body and mind. For what lay concealed behind this vague and schematic word, were extermination, gas, and death. It would go too far if I enumerated all of these decrees issued against Jews. But none of this could compare to the events that began in autumn of 1940, when trucks roared down the streets at night and when the mass deportations of Jews to concentration camps and Polish ghettos commenced.

The first victims affected by this roundup were those judged unfit for forced labour: the elderly, the sick, and the children. Once they had been deported, all Jewish workers were next in line because the Nazis had developed a necessary back-up plan. The newly created vacuum in the labor force would be filled by “foreign workers,” a new category of slaves. For this reason, on January 29, l943, my wife and I had been marked for arrest and deportation. My wife’s sister and several other Jews living in our apartment – each Jew was granted a mere 120 sq.ft. of living space – did not escape their fate. They were dragged from their homes in our neighbourhood on the very same night, as were other relatives and acquaintances. We never heard from them again.

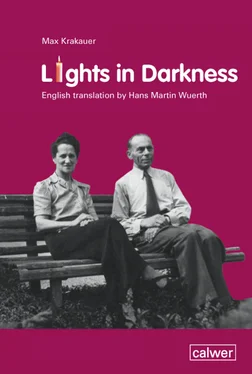

This brings me to the phase of our experience within the Nazi regime that became the real reason for writing my book. The book’s purpose is to show how during these years a number of individuals, families, and institutions, rescued the two of us who were persecuted and hunted by the Gestapo. And this happened in Germany, a country that presented itself to the outside world in the cloak of murderers. These rescuers risked their own lives as well as the existence of their families, often regardless of personal privation and hardships. How infinitely difficult this had been; it was much more dangerous than is generally known, for what spread more abundantly in Germany than weeds in open fields were acts of denunciation. Never will we, or anyone else who witnessed the deep convictions of our rescuers, be able to thank them fully for having saved us from the fangs of Hitler’s henchmen. I know they wanted no gratitude and did not desire earthly rewards and gratitude; but rather, they were motivated by human love and Christian compassion. They wished to do something before God for reasons of conscience, hoping that this would diminish or make up for the bitter injustices committed against human beings whose only violation was to be of Jewish descent. They risked their freedom and their lives. They were the good Samaritans of the Third Reich.

It was January 29, 1943. My wife was cold and miserable and barely made it home from work. As she reached for the door handle, a figure emerged from the darkness near a wall. A shaking hand reached for her arm and a voice whispered, “The Gestapo is inside your apartment. Get away from here fast! Go away! Quickly!” It was a woman, a Christian friend, who had been waiting to warn my wife. All of the Jews living with us were targeted for “evacuation,” including my wife’s only living sister, a widow. (Besides us, there were nine others, included two individuals who had not been marked at that time for deportation due to their mixed marriage.)

My wife, half conscious from shock and fear, escaped into the darkness of night. What would happen to me? she wondered. Early that day, we had decided that I should see a doctor after work. Suppose I hadn’t done that for some reason, she wondered, and instead, I would be on my way home? Suppose she wouldn’t meet me now and I would walk into the hands of the Gestapo who would arrest me? What if I were taken away, and she would have to stay here alone? But a bit of luck was on our side: she caught up with me in the doctor’s waiting room. Both of us had escaped our captors, but we couldn’t return home. We decided to spend at least this night at a friend’s place, with a woman whose husband had been in jail for some time following a minor offence. This woman lived with a couple of a mixed marriage. After a lengthy discussion, we received permission to sleep on our friend’s sofa. We knew quite well that what we asked for would subject the entire family to severe danger. Even the homes of Jews of a mixed marriage were checked by the Gestapo at any time, day and night. Although Jews could not be on public streets after 8:00 in the evening (or 9:00 in summertime), I dared to sneak over to the Kurfürstendamm to look at our home from a distance. Everything was brightly lit. So here they were, these persecutors, waiting for our return! As I found out later, they awaited our return well into the early hours of the next day.

Long before daybreak we left our shelter. We sensed our hosts’ fears that our presence would subject them to great danger, and that they no longer wanted us around. Once again we were out in the streets. Where would we go from here? My first thought was to stay away from our home for this night only, then to return to work on the next morning, pretending that nothing had happened, and with the vague hope that the Gestapo perhaps would not bother us again. But this option was quickly eliminated, because in the meantime the Gestapo had placed our home under lock and key. Did another effort on our part make any sense at all? Who would provide help to two Jews on the run, here in the heart of the Third Reich? Wasn’t it sheer nonsense to try to escape Himmler’s henchmen? Was it not better to simply report to the Gestapo?

Confused and indecisive, we consulted one of my former colleagues who had been hired by the Gestapo as an orderly for the deportation of Jews. He must have been well informed about our imminent fate if we decided to turn ourselves in. He pleaded with us, yes, he implored us, to cancel our plan and to stay in hiding for as long as possible. We left convinced that we would not be successful for very long although we were willing to try. In the afternoon we went to the Christian widow of a Jewish friend, who had perished in a notorious camp near the Pyrenees to which all Germans were taken, Jews and Christians alike, on the day of Germany’s invasion of Belgium on May 10, 1940. We were allowed to stay for one night, but only if we were extremely cautious. Two women were renting the rooms downstairs, both civil servants and National Socialists, who under no circumstances should became aware of our presence.

Читать дальше