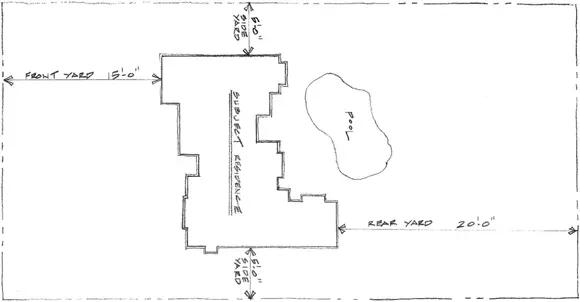

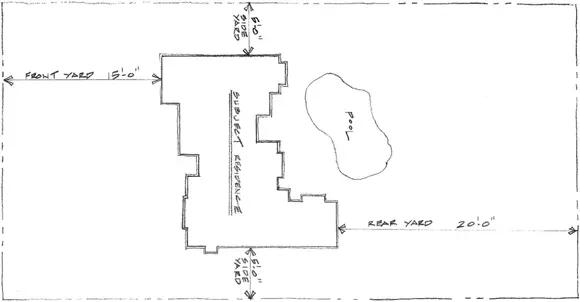

Understanding setbacks and footprints

Setbacks determine how far from the edges of your lot you must build. They’re generally determined by the property zoning restrictions and the CC&Rs. The side setbacks are generally closer to the property line than the front and rear setbacks, but not always. This information is crucial for figuring out where you can place the house on the lot. Many neighborhoods like to keep the houses uniform, so look to see how close neighbors’ houses are to the street and each other to get a feel for the setbacks. In urban areas, the side setbacks may be as small as only a few feet (Peter’s old house in San Diego had a side setback of only 3 feet — barely enough room to wheel his trashcan through to the street every Monday night). Rural areas can require larger setbacks from the street or other houses, impacting curb appeal.

Setbacks also apply to outbuildings, not just to the main house. On larger lots, you may be considering the possibility of a guesthouse, workshop, or pool house within the buildable area. These buildings all have to be within a certain area defined by the setbacks.

Setbacks also apply to outbuildings, not just to the main house. On larger lots, you may be considering the possibility of a guesthouse, workshop, or pool house within the buildable area. These buildings all have to be within a certain area defined by the setbacks.

The footprint of the home is the building’s outer perimeter and how it sits upon the lot, taking into account the setbacks (see Figure 3-1). When looking at a lot, try to imagine in rough design how positioning the footprint can take advantage of the following:

Drainage

Noise

Sunlight

Topography

Views

Wind

Courtesy of Tecta Associates Architects, San Francisco

FIGURE 3-1:Setbacks determine the placement of your footprint, ultimately restricting your home’s size.

The combination of footprint and setbacks may dictate whether your house is one story or more. Significant side setbacks can force you to design a smaller-footprint home, which can make a difference in estimating building costs. A smaller building area may mean that building a second floor is essential. Building a second floor can work to your advantage, however, because a two-story house can be less expensive to build than a one-story house. (For example, building a two-story house with 4,000 square feet is cheaper than building a one-story house with the same square feet. The two-story house requires less excavation, foundation, and roof work than the one-story house does.)

Height restrictions spelled out in the CC&Rs have an impact on your house’s size. If your setbacks force a smaller footprint, then your height restriction will limit the size of house you can build. Have your real-estate agent obtain this information for you before you purchase the lot to make sure it meets your needs. You can also contact the local planning department to access the information yourself.

Size matters: Assessing the land’s value with the house

Even though much of the planning for your new home is considered in the design phase that we discuss in Chapter 4, considering the planned size of your house when purchasing the lot is important. You can’t build any house you want on any lot. You’ll probably face restrictions set by the city, county, and sometimes the market. Doing your homework on the limitations of what can be built on a lot can keep you from making costly mistakes.

How do you know for sure that the land you want to buy is going to fit within your budget? You must consider it in the context of the budget for your entire custom-home-building project. (See Chapter 2for information on budgeting.) Start by researching the sale prices of houses in the area. If homes in the neighborhood are selling for $500,000, then buying a comparable lot for $375,000 isn’t likely to leave you with financial room to build.

Still not sure what to do? Here’s our quick-and-dirty four-step process for getting a rough idea whether a lot is too expensive:

Still not sure what to do? Here’s our quick-and-dirty four-step process for getting a rough idea whether a lot is too expensive:

1 Contact a real-estate agent and get a list of properties that have sold in the area during the last year.Make sure the list includes the square footage and room count of each home.

2 Pick the three sale prices that are most similar to the house in square footage and room count that you want to build, and average the sales prices.Most lenders use at least three comparable sales to establish an appraised value, so this number helps you evaluate the property from the lender’s perspective. If no home sales are similar to your desired home in square footage and room count, then you may need to reassess your design or your choice of neighborhood.

3 Subtract the land price from the average sales price and divide by the square footage you want to build.Doing so gives you a rough number for dollars per square foot. (We explain dollars per square foot in detail in Chapter 2.)

4 Call three contractors in the area and ask if they can build for the dollars per square foot number you established in Step 3.The contractors you call at this point can be referrals, names you find online, or business cards you find at The Home Depot. Where you locate them doesn’t really matter because you may not use them for your project anyway — you simply want a rough survey. (For more information on choosing a contractor, check out Chapter 2.)

Taking these steps can give you a rough idea whether you’re even close. This method, of course, does have many variables and unanswered questions, such as the selection of your fixtures and materials and foundational needs. However, if all three contractors you contact are rolling on the floor with laughter, you’re probably looking at an overpriced lot.

A tale of two lot buyers: How square footage impacts value

Kevin relates this experience from a custom-home project he financed in Northern California.

Ten newly divided lots were being sold for $200,000 in an established neighborhood. Frank Smith looked at one of the lots and was concerned because he thought the lot was too expensive. He was absolutely right. Maria Garcia came in the same day and looked at the same lot and quickly determined the lot was a great deal. She was also absolutely right.

How can they both be right if they’re talking about the same lot? The decision is all about the square footage. Frank wanted to build a 2,500-square-foot house, which was comparable to other houses in the neighborhood selling for $600,000. The total cost of the house including the land penciled out to $650,000, making the project too expensive to build on this lot. Frank wouldn’t be able to borrow enough money to build his house.

Maria’s house was going to be 4,500 square feet. Her cost per square foot was the same as Frank’s, so her total cost for the project including land would be $875,000. Houses of this size in the same neighborhood were selling for $950,000, allowing Maria a $75,000 profit on her house, which allowed Maria to borrow plenty of money to build it.

Your real-estate agent can show you the sales from the last year to evaluate the optimal house for your neighborhood, which can help you make sound choices for maximum value and the best financing.

Your real-estate agent can show you the sales from the last year to evaluate the optimal house for your neighborhood, which can help you make sound choices for maximum value and the best financing.

Dealing with a Teardown Property

Читать дальше

Setbacks also apply to outbuildings, not just to the main house. On larger lots, you may be considering the possibility of a guesthouse, workshop, or pool house within the buildable area. These buildings all have to be within a certain area defined by the setbacks.

Setbacks also apply to outbuildings, not just to the main house. On larger lots, you may be considering the possibility of a guesthouse, workshop, or pool house within the buildable area. These buildings all have to be within a certain area defined by the setbacks.

Still not sure what to do? Here’s our quick-and-dirty four-step process for getting a rough idea whether a lot is too expensive:

Still not sure what to do? Here’s our quick-and-dirty four-step process for getting a rough idea whether a lot is too expensive: