1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...36

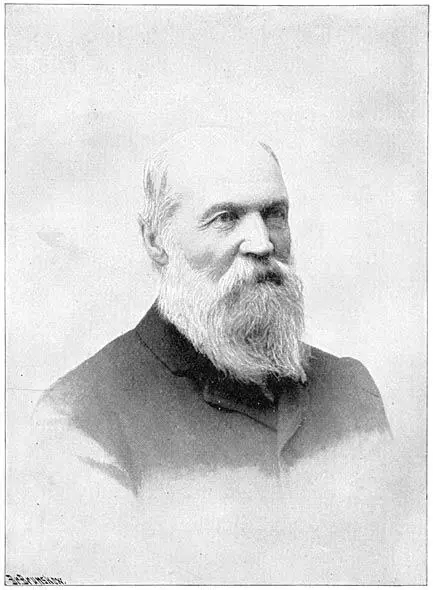

Colin Archer

If we turn our attention to the long list of former expeditions and to their equipments, it cannot but strike us that scarcely a single vessel had been built specially for the purpose—in fact, the majority of explorers have not even provided themselves with vessels which were originally intended for ice navigation. This is the more surprising when we remember the sums of money that have been lavished on the equipment of some of these expeditions. The fact is, they have generally been in such a hurry to set out that there has been no time to devote to a more careful equipment. In many cases, indeed, preparations were not begun until a few months before the expedition sailed. The present expedition, however, could not be equipped in so short a time, and if the voyage itself took three years, the preparations took no less time, while the scheme was conceived thrice three years earlier.

Plan after plan did Archer make of the projected ship; one model after another was prepared and abandoned.

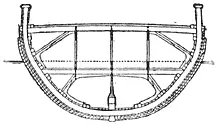

Fresh improvements were constantly being suggested. The form were finally adhered to may seem to many people by no means beautiful; but that it is well adapted to the ends in view I think our expedition has fully proved. What was especially aimed at was, as mentioned on page 29, to give the ship such sides that it could readily be hoisted up during ice-pressure without being crushed between the floes. Greely, Nares, etc., etc., are certainly right in saying that this is nothing new. I relied here simply on the sad experiences of earlier expeditions. What, however, may be said to be new is the fact that we not only realized that the ship ought to have such a form, but that we gave it that form, as well as the necessary strength for resisting great ice-pressure, and that this was the guiding idea in the whole work of construction. Colin Archer is quite right in what he says in an article in the Norsk Tidsskrift for Sövæsen , 1892: “When one bears in mind what is, so to speak, the fundamental idea of Dr. Nansen’s plan in his North Pole Expedition … it will readily be seen that a ship which is to be built with exclusive regard to its suitability for this object must differ essentially from any other previously known vessel. …

“In the construction of the ship two points must be especially studied: (1) that the shape of the hull be such as to offer as small a vulnerable target as possible to the attacks of the ice; and (2) that it be built so solidly as to be able to withstand the greatest possible pressure from without in any direction whatsoever.”

And thus she was built, more attention being paid to making her a safe and warm stronghold while drifting in the ice than to endowing her with speed or good sailing qualities.

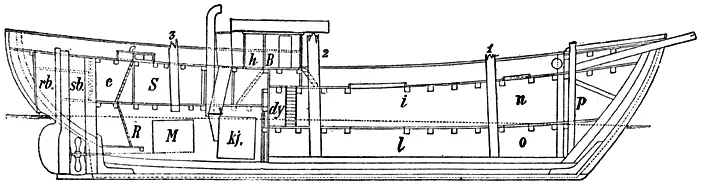

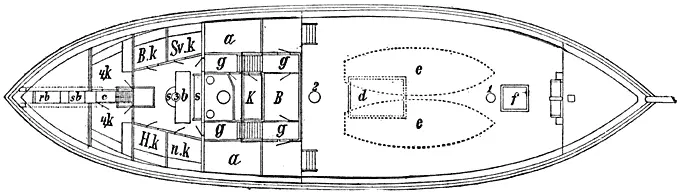

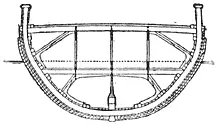

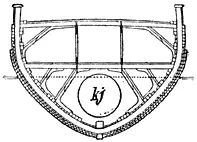

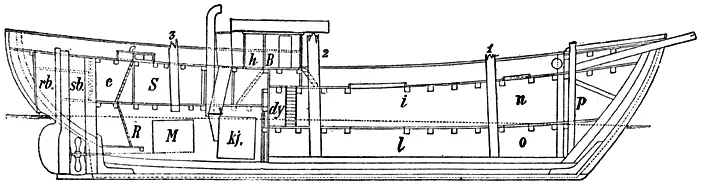

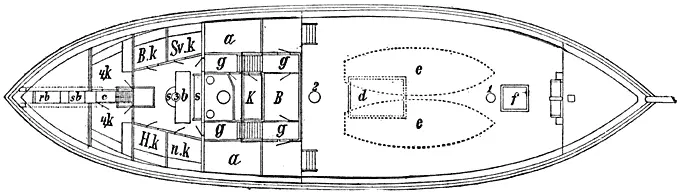

Designs for the “Fram”

Fig. 1. Longitudinal section.

Fig. 2. Plan.

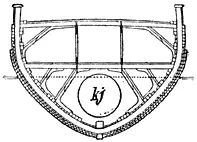

Fig. 3. Transverse section amidships.

Fig. 4. Transverse section at the engine-room.

rb Rudder-well. sb Propeller-well. S Saloon. s Sofas in saloon. b Table in saloon. Svk Sverdrup’s cabin. Bk Blessing’s cabin. 4k Four-berth cabins. Hk Scott-Hansen’s cabin. nk Nansen’s cabin. c Way down to engine-room. R Engine-room. M Engine. kj Boiler. g Companions leading from saloon. K Cook’s galley. B Chart-room. h Work-room. dy Place for the dynamo. d Main-hatch. e Long boats. i Main-hold. l Under-hold. f Fore-hatch. n Fore-hold. o Under fore-hold. p Pawl-bit. 1 Foremast. 2 Mainmast. 3 Mizzenmast.

As above stated, our aim was to make the ship as small as possible. The reason of this was that a small ship is, of course, lighter than a large one, and can be made stronger in proportion to her weight. A small ship, too, is better adapted for navigation among the ice; it is easier to handle her in critical moments, and to find a safe berth for her between the packing ice-floes. I was of opinion that a vessel of 170 tons register would suffice, but the Fram is considerably larger, 402 tons gross and 307 tons net. It was also our aim to build a short vessel, which could thread her way easily among the floes, especially as great length would have been a source of weakness when ice-pressure set in. But in order that such a ship, which has, moreover, very sloping sides, shall possess the necessary carrying capacity, she must be broad; and her breadth is, in fact, about a third of her length. Another point of importance was to make the sides as smooth as possible, without projecting edges, while plane surfaces were as much as possible avoided in the neighborhood of the most vulnerable points, and the hull assumed a plump and rounded form. Bow, stern, and keel—all were rounded off so that the ice should not be able to get a grip of her anywhere. For this reason, too, the keel was sunk in the planking, so that barely three inches protruded, and its edges were rounded. The object was that “the whole craft should be able to slip like an eel out of the embraces of the ice.”

The hull was made pointed fore and aft, and somewhat resembles a pilot-boat, minus the keel and the sharp garboard strakes. Both ends were made specially strong. The stem consists of three stout oak beams, one inside the other, forming an aggregate thickness of 4 feet (1.25 m.) of solid oak; inside the stem are fitted solid breasthooks of oak and iron to bind the ship’s sides together, and from these breasthooks stays are placed against the pawl-bit. The bow is protected by an iron stem, and across it are fitted transverse bars which run some small distance backwards on either side, as is usual in sealers.

The stern is of a special and somewhat particular construction. On either side of the rudder and propeller posts—which are sided 24 inches (65 cm.)—is fitted a stout oak counter-timber following the curvature of the stern right up to the upper deck, and forming, so to speak, a double stern-post. The planking is carried outside these timbers, and the stern protected by heavy iron plates wrought outside the planking.

Between these two counter-timbers there is a well for the screw, and also one for the rudder, through which they can both be hoisted up on deck. It is usual in sealers to have the screw arranged in this way, so that it can easily be replaced by a spare screw should it be broken by the ice. But such an arrangement is not usual in the case of the rudder, and, while with our small crew, and with the help of the capstan, we could hoist the rudder on deck in a few minutes in case of any sudden ice-pressure or the like, I have known it take sealers with a crew of over 60 men several hours, or even a whole day, to ship a fresh rudder.

The stern is, on the whole, the Achilles’ heel of ships in the Polar Seas; here the ice can easily inflict great damage, for instance, by breaking the rudder. To guard against this danger, our rudder was placed so low down as not to be visible above water, so that if a floe should strike the vessel aft, it would break its force against the strong stern-part, and could hardly touch the rudder itself. As a matter of fact, notwithstanding the violent pressures we met with, we never suffered any injury in this respect.

Читать дальше