It is a moot question who first multiplied the figures from the trigrams universally ascribed to Fû-hsî to the 64 hexagrams of the Yî The more common view is that it was king Wăn; but K û Hsî, when he was questioned on the subject, rather inclined to hold that Fû-hsî had multiplied them himself, but declined to say whether he thought that their names were as old as the figures themselves, or only dated from the twelfth century B.C. 3I will not venture to controvert his opinion about the multiplication of the figures, but I must think that the names, as we have them now, were from king Wăn.

No Chinese writer has tried to explain why the framers stopped with the 64 hexagrams, instead of going on to 128 figures of 7 lines, 256 of 8, 512 of 9, and so on indefinitely. No reason can be given for it, but the cumbrousness of the result, and the impossibility of dealing, after the manner of king Wăn, with such a mass of figures.

(iii) The 73rd paragraph of Section i, with but one paragraph between it and the two others which we have been considering, gives what may be considered a third account of the origin of the lineal figures:--

'Heaven produced the spirit-like things (the tortoise and the divining plant), and the sages took advantage of them. (The operations of) heaven and earth are marked by so many changes and transformations, and the sages imitated them (by means of the Yî). Heaven hangs out its (brilliant) figures, from which are seen good fortune and bad, and the sages made their emblematic interpretations accordingly. The Ho gave forth the scheme or map, and the Lo gave forth the writing, of (both of) which the sages took advantage.'

The words with which we have at present to do are 'The Ho (that is, the Yellow River) gave forth the Map.' This map, according to tradition and popular belief, contained a scheme which served as a model to Fû-hsî in making his 8 trigrams. Apart from this passage in the Yî King, we know that Confucius believed in such a map, or spoke at least as if he did 4. In the 'Record of Rites' it is said that 'the map was borne by a horse 5;' and the thing, whatever it was, is mentioned in the Shû as still preserved at court, among other curiosities, in B.C. 1079 6. The story of it, as now current, is this, that 'a dragon-horse' issued from the Yellow River, bearing on its back an arrangement of marks, from which Fû-hsî got the idea of the trigrams.

All this is so evidently fabulous that it seems a waste of time to enter into any details about it. My reason for doing so is a wish to take advantage of the map in giving such a statement of the rules observed in interpreting the figures as is necessary in this Introduction.

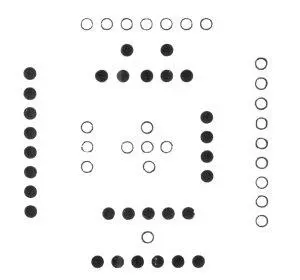

The map that was preserved, it has been seen, in the eleventh century B.C., afterwards perished, and though there was much speculation about its form from the time that the restoration of the ancient classics was undertaken in the Han dynasty, the first delineation of it given to the public was in the reign of Hui Ȝung of the Sung dynasty (A. D. 1101-1125) 7. The most approved scheme of it is the following:--

It will be observed that the markings in this scheme are small circles, pretty nearly equally divided into dark and light. All of them whose numbers are odd are light circles, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9; and all of them whose numbers are even are dark,--2, 4, 6, 8, 10. This is given as the origin of what is said in paragraphs 49 and 50 of Section i about the numbers of heaven and earth. The difference in the colour of the circles occasioned the distinction of them and of what they signify into Yin and Yang, the dark and the bright, the moon-like and the sun-like; for the sun is called the Great Brightness (Thâi Yang), and the moon the Great Obscurity (Thâi Yin). I shall have more to say in the next chapter on the application of these names. Fû-hsî in making the trigrams, and king Wăn, if it was he who first multiplied them to the 64 hexagrams, found it convenient to use lines instead of the circles:--the whole line (  ) for the bright circle (

) for the bright circle (  ), and the divided line (

), and the divided line (  ) for the dark (

) for the dark (  ). The first, the third, and the fifth lines in a hexagram, if they are 'correct' as it is called, should all be whole, and the second, fourth, and sixth lines should all be divided. Yang lines are strong (or hard), and Yin lines are weak (or soft). The former indicate vigour and authority; the latter, feebleness and submission. It is the part of the former to command; of the latter to obey.

). The first, the third, and the fifth lines in a hexagram, if they are 'correct' as it is called, should all be whole, and the second, fourth, and sixth lines should all be divided. Yang lines are strong (or hard), and Yin lines are weak (or soft). The former indicate vigour and authority; the latter, feebleness and submission. It is the part of the former to command; of the latter to obey.

The lines, moreover, in the two trigrams that make up the hexagrams, and characterise the subjects which they represent, are related to one another by their position, and have their significance modified accordingly. The first line and the fourth, the second and the fifth,. the third and the sixth are all correlates; and to make the correlation perfect the two members of it should be lines of different qualities, one whole and the other divided. And, finally, the middle lines of the trigrams, the second and fifth, that is, of the hexagrams, have a peculiar value and force. If we have a whole line (  ) in the fifth place, and a divided line (

) in the fifth place, and a divided line (  ) in the second, or vice versâ, the correlation is complete. Let the subject of the fifth be the sovereign or a commander-in-chief, according to the name and meaning of the hexagram, then the subject of the second will be an able minister or a skilful officer, and the result of their mutual action will be most beneficial and successful. It is specially important to have a clear idea of the name of the hexagram, and of the subject or state which it is intended to denote. The significance of all the lines comes thus to be of various application, and will differ in different hexagrams.

) in the second, or vice versâ, the correlation is complete. Let the subject of the fifth be the sovereign or a commander-in-chief, according to the name and meaning of the hexagram, then the subject of the second will be an able minister or a skilful officer, and the result of their mutual action will be most beneficial and successful. It is specially important to have a clear idea of the name of the hexagram, and of the subject or state which it is intended to denote. The significance of all the lines comes thus to be of various application, and will differ in different hexagrams.

I have thus endeavoured to indicate how the lineal figures were formed, and the principal rules laid down for the interpretation of them. The details are wearying, but my position is like that of one who is called on to explain an important monument of architecture, very bizarre in its conception and execution. A plainer, simpler structure might have answered the purpose better, but the architect had his reasons for the plan and style which he adopted. If the result of his labours be worth expounding, we must not grudge the study necessary to detect his processes of thought, nor the effort and time required to bring the minds of others into sympathy with his.

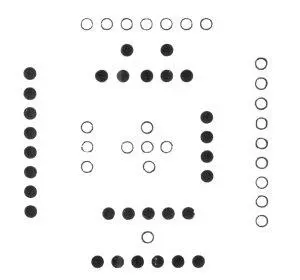

My own opinion, as I have intimated, is, that the second, account of the origin of the trigrams and hexagrams is the true one. However the idea of the whole and divided lines arose in the mind of the first framer, we must start from them; and then, manipulating them in the manner described, we arrive, very easily, at all the lineal figures, and might proceed to multiply them to billions. We cannot tell who devised the third account of their formation from the map or scheme on the dragon-horse of the, Yellow River 8. Its object, no doubt, was to impart a supernatural character to the trigrams and produce a religious veneration for them. It may be doubted whether the scheme as it is now fashioned be the correct one,--such as it was in the K âu dynasty. The paragraph where it is mentioned, goes on to say--'The Lo produced the writing.' This writing was a scheme of the same character as the Ho map, but on the back of a tortoise, which emerged from the river Lo, and showed it to the Great Yü, when he was engaged in his celebrated work of draining off the waters of the flood, as related in the Shû. To the hero sage it suggested 'the Great Plan,' an interesting but mystical document of the same classic, 'a Treatise,' according to Gaubil, 'of Physics, Astrology, Divination, Morals, Politics, and Religion,' the great model for the government of the kingdom. The accepted representation of this writing is the following:--

Читать дальше

) for the bright circle (

) for the bright circle (  ), and the divided line (

), and the divided line (  ) for the dark (

) for the dark (  ). The first, the third, and the fifth lines in a hexagram, if they are 'correct' as it is called, should all be whole, and the second, fourth, and sixth lines should all be divided. Yang lines are strong (or hard), and Yin lines are weak (or soft). The former indicate vigour and authority; the latter, feebleness and submission. It is the part of the former to command; of the latter to obey.

). The first, the third, and the fifth lines in a hexagram, if they are 'correct' as it is called, should all be whole, and the second, fourth, and sixth lines should all be divided. Yang lines are strong (or hard), and Yin lines are weak (or soft). The former indicate vigour and authority; the latter, feebleness and submission. It is the part of the former to command; of the latter to obey.