In the early days of colonization, the labor force in the French islands included both white indentured servants and enslaved blacks. As the sugar boom created a growing demand for workers, however, plantation-owners throughout the Caribbean became more and more dependent on Africans to work their fields. After the end of Louis XIV’s long series of wars in 1713, the French slave trade expanded rapidly. Throughout the eighteenth century, slave ships left the ports on France’s Atlantic coast, carrying trade goods to the coast of Africa. There, they exchanged textiles, muskets, and jewelry for black men and women, often captives taken in wars between rival African states. Packed into the holds of overcrowded vessels, the terrified blacks knew only that they would never see their families and homelands again. Close to a sixth of the captives on a typical voyage died from disease or mistreatment before reaching the Americas. Those who arrived in Saint-Domingue were promptly put up for sale and found themselves taken off to plantations where, if they were lucky, they might encounter a few fellow blacks who spoke their native language. In this strange new world, they had to struggle to make some kind of life for themselves, under the control of masters whose only interest was in extracting the maximum amount of useful labor from them.

Eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue was a classic example of what historians call a “slave society,” one in which the institution of slavery was central to every aspect of life, in contrast to “societies with slaves,” in which slaves were a relatively small part of the population and most economic activity was carried on by free people. Organized in work gangs or ateliers , enslaved blacks in Saint-Domingue performed almost all of the exhausting physical labor on which the growing and processing of sugar and coffee depended. Much of the field work – hoeing fields to clear away weeds, planting, and harvesting – was done by women; men were often trained to do more skilled jobs, such as sugar-processing, carpentry, or, like the future Toussaint Louverture, serving as coachmen. Children were assigned to a special petit atelier as early as possible, to accustom them to work, and those too old or sick to toil in the fields were used to guard the plantation’s animals or its storeroom. At the top of the hierarchy among the enslaved workers were the commandeurs or drivers, who directed the work in the fields. The smooth functioning of a plantation depended on the commandeurs : even though the commandeurs were enslaved themselves, plantation-owners and managers treated them with respect to maintain their authority over the rest of the workforce. While most enslaved workers on the plantations worked in the fields or processed sugar and coffee, some were used as domestic servants for the masters and their families. The one skilled job usually reserved for women was the direction of the infirmary; supervising the care of the sick and ferreting out malingerers who were trying to escape work was an important task in the overall management of a plantation.

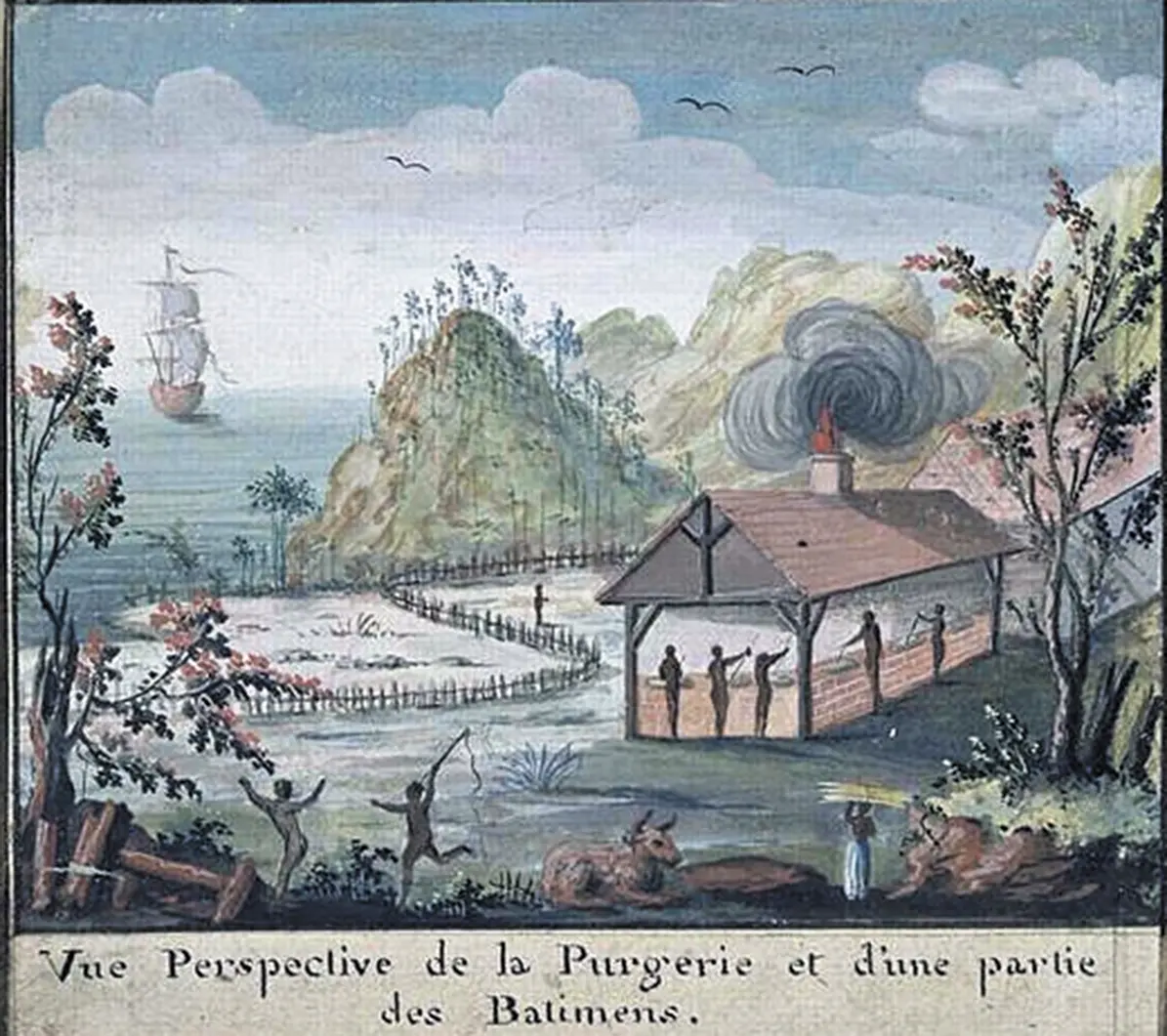

Caribbean sugar plantations were notorious for the demands they placed on their captive work force and the cruelty with which they were treated (see Figure 1.1). A French observer in the 1780s described the scene he witnessed in Saint-Domingue’s sugar fields: “The sun blazed down on [the enslaved blacks’] heads; sweat poured from all parts of their bodies. Their limbs, heavy from the heat, tired by the weight of their hoes and the resistance of heavy soil, which was hardened to the point where it broke the tools, nonetheless struggled to overcome all obstacles. They worked in glum silence; all their faces showed their misery.” 2Sugar cane had to be processed as soon as it was cut, before the precious juice began to turn to starch and lose its sweetness. During the long harvesting season, from January to July every year, cane was cut in the fields and immediately fed through the heavy rollers of the crushing machine. The extracted juice then had to be boiled for hours in large cauldrons, while enslaved laborers stirred the syrup in the sweltering heat; it was then poured into molds so that the sugar could crystallize. The same workers who had toiled in the fields during the day were forced to work making sugar long into the night, and accidents caused by exhaustion were frequent; women who had to feed the cane stalks into crushing machines often lost arms that got caught in the machinery. Work on coffee plantations was not driven by the same need for haste as that involved in sugar production, but the endless routine of planting and caring for the trees, harvesting the beans, spreading them out to dry in the sun, and processing them kept enslaved workers equally busy. In addition to working for their masters, black captives were responsible for producing most of their own food: masters usually gave them small private plots to raise yams, beans, and other vegetables for themselves. In theory, they were supposed to be guaranteed one day a week to cultivate these gardens, but masters never hesitated to commandeer them for other tasks; the enslaved blacks had to make do with whatever free time they could find to tend their crops.

Figure 1.1 Plantations and enslaved labor. An image commissioned by a French plantation-owner around 1780 shows the “purgerie,” where enslaved blacks worked to refine sugarcane juice into sugar for export. In the foreground, a black woman on the right carries cane stalks to be processed, while on the left, a man with a raised whip chases another woman. Even at the height of the Enlightenment period, European whites were not embarrassed by the cruelty and the exploitative nature of the slavery system.

Source : © RMN-Blérancourt, Musée franco-américain du château de Blérancourt.

Living conditions for enslaved blacks on the plantations were harsh. Although Europeans considered blacks uniquely suited to work in the hot Caribbean climate because it resembled the weather in Africa, newly arrived captives fell victim to unfamiliar diseases in their new environment or succumbed to depression resulting from the traumatic ordeal they had been through; as many as a third of them died in their first year in the colonies. The average life expectancy of a enslaved black after arriving in Saint-Domingue was no more than seven to ten years. Most of them suffered from chronic malnutrition: the system of private plots rarely sufficed to provide enough food, and above all they were deprived of meat, a basic element of their diet in Africa. Slaveowners were theoretically obliged to supply their captives with adequate clothing, but few of them paid attention to this rule, and blacks often had only rags to wear or were forced to go around half-naked. Left to themselves, they tried to build huts similar to those familiar to them from Africa, but masters often preferred to force them to live in larger buildings where they could be supervised more easily. Masters discouraged marriages among their captives, for fear that having their own families would give them a sense of independence. Newly arrived blacks, called bossales , were sometimes put under the supervision of veterans who spoke their native language, but they still had to learn Kreyol, a combination of elements of French and various African languages that served as the general medium of communication in the colony. At the time of the revolution, African-born bossales made up at least half of the Saint-Domingue population. Many of the newly arrived captives at the time of the revolution had military experience, having been taken prisoner in wars in the Congo region of Africa; they would make an important contribution to the uprising that began in 1791. 3Masters considered enslaved blacks born in the colony, known as creoles , easier to manage than the bossales ; the creoles s grew up speaking the local language and had never known any life outside of the slave system.

Читать дальше