For Haitians themselves, the story of their ancestors’ struggle for freedom has great symbolic importance, and its heroes remain sources of inspiration to a population facing what often seem like insurmountable challenges. This account, constrained by the guidelines of modern historical research, may strike some readers as less vivid than the colorful scenes of revolutionary events painted by many of Haiti’s talented contemporary artists. Reconciling the living historical memory of the Haitian Revolution with the results of modern historical research is not a simple task. Nevertheless, historians’ attempts to understand the events of the revolutionary period as the outcome of the actions of the men and women who participated in them have their own value, even if the historical record is not complete enough to answer all our questions. The aim of this book is, then, to provide students and general readers with a concise overview of the generally accepted historical facts about the Haitian Revolution, drawing on the scholarship of historians from Haiti itself as well as the research of those in the United States, Europe, and other countries who have contributed to the subject.

For much of the period from the declaration of Haitian independence in 1804 until the last decades of the twentieth century, serious historical scholarship on this subject by scholars outside Haiti remained quite limited. Haitian historians have produced many important works on the subject, despite the fact that most of the surviving documents about the revolution are in archives in France and not in Haiti itself, but their books, usually published in French, are often hard to find except in major research libraries. Outside of Haiti, few historians were attracted to a subject that inevitably raised troubling questions about the policies of the French Revolution and the national hero Napoleon, and that reminded Americans that the United States had refused to recognize Haiti’s freedom for six decades. In recent decades, what the Haitian American scholar Michel-Rolph Trouillot eloquently denounced in a famous essay as the “silencing” of the Haitian Revolution for so long has begun to end. 3In writing this short history, I have been able to draw on a rapidly growing body of modern scholarship from both sides of the Atlantic; the recommendations for further reading at the end of this book will point readers to many of the sources I have used. If this book encourages readers to explore the subject further on their own, it will have achieved its purpose.

1 A Colonial Society in a Revolutionary Era

The beginning of the Haitian Revolution in August 1791 shocked the entire Atlantic world because it occurred, not in some remote backwater of the Americas, but in the fastest-growing and most prosperous of all the New World colonies. By 1791 Europeans had been staking out territory across the Atlantic and importing African captives to work for them for 300 years, but nowhere else had this colonial system been made to function as successfully as in Saint-Domingue. In the 28 years since the end of the eighteenth century’s largest conflict, the Seven Years War, in 1763, the population of the French colony had nearly doubled as plantation-owners ca2shed in on Europe’s seemingly unquenchable appetite for sugar and coffee. Imports of enslaved Africans to the island averaged over 15,000 a year in the late 1760s; after an interruption caused by the American War of Independence, they soared to nearly 30,000 in the late 1780s. No other slaveowners had learned to exploit their workforce with such harsh efficiency: by 1789, there were nearly 12 enslaved blacks for every white inhabitant, and the wealthiest Saint-Domingue plantation-owners were far richer than Virginians like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Cap Français, the colony’s largest city, was one of the New World’s busiest ports; on an average day, more than 100 merchant ships lay at anchor in its broad harbor. The city itself, with its geometrically laid-out streets and its modern public buildings, was a symbol of European civilization in the tropics.

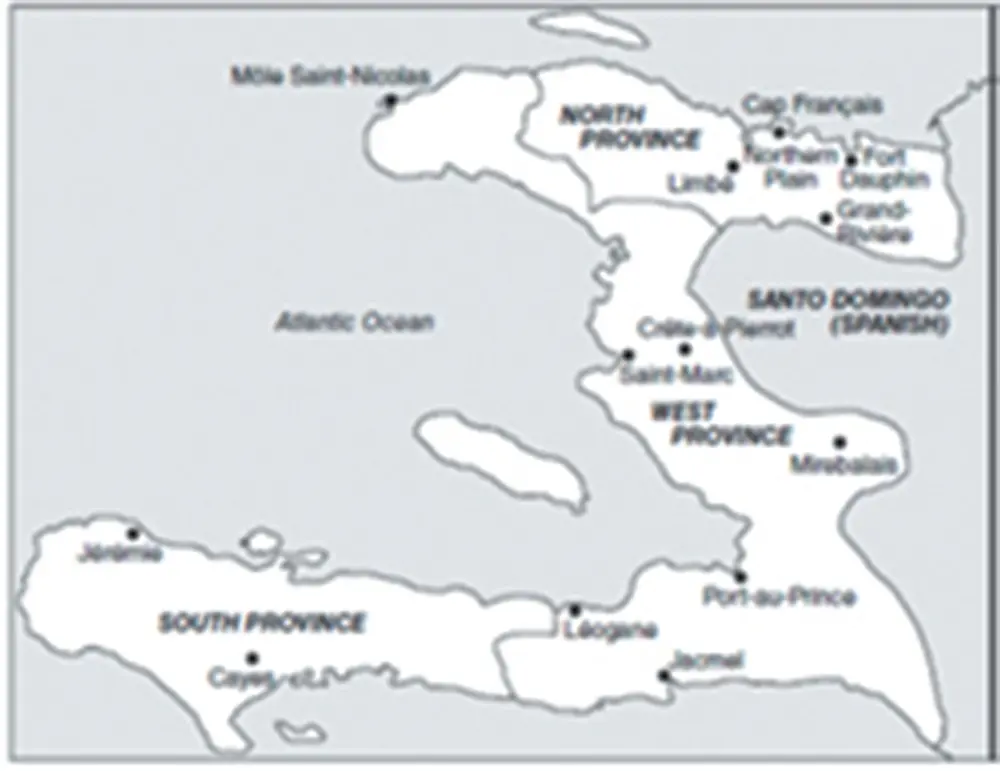

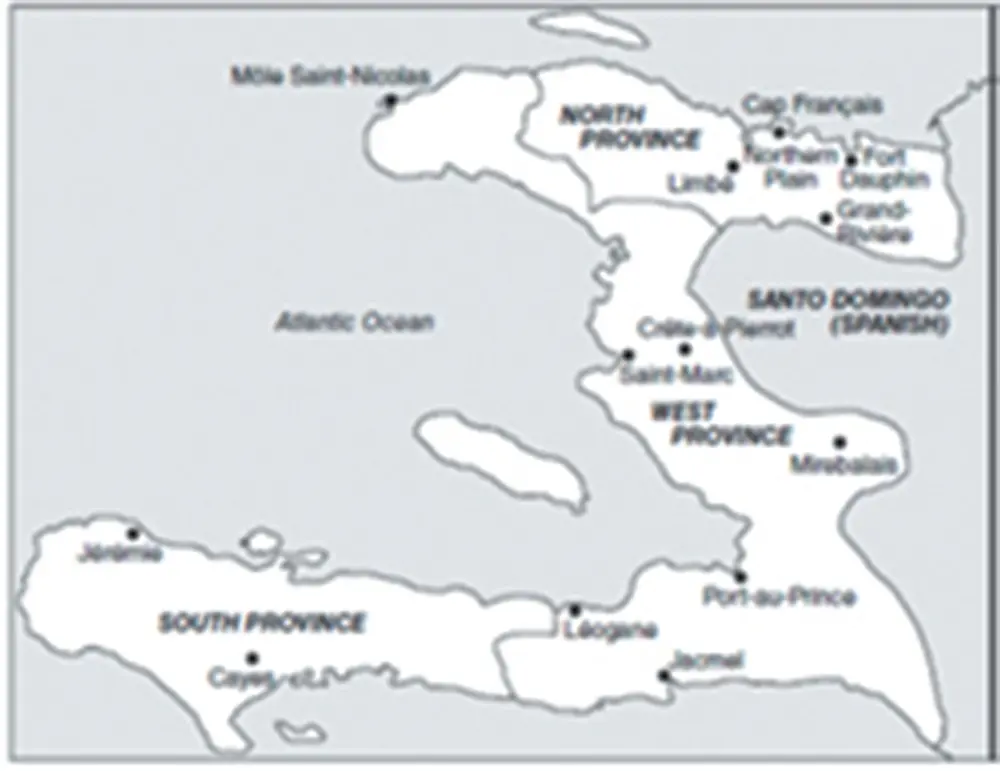

Map 2The French Colony of Saint-Domingue in 1789.

Source : Adapted from Jeremy Popkin, Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Uprising (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

The Origins of Saint-Domingue

The island of Hispaniola, where Saint-Domingue was located, had been the site of one of the first contacts between Europeans and the peoples of the Americas: Columbus landed on its northern coast during his first voyage in 1492. The Spanish made it the first hub of their empire in the New World; the diseases they brought with them and their harsh exploitation of the population soon killed off the native Taino Indians. By the end of the 1500s, however, the Spanish had found richer opportunities for settlement in Mexico, Peru, and other parts of the Americas. Lacking gold and other easily exploitable resources, Hispaniola was virtually abandoned. During the early decades of the 1600s, the English, French, and Dutch, initially shut out of the scramble for territories on the American continents by the first arrivals, the Spanish and the Portuguese, began staking claims to some of the islands in the Caribbean. France established its first permanent colonial settlement on the small island of Saint-Christophe in 1626; in 1635, the French planted their flag on two larger islands in the eastern Caribbean, Martinique and Guadeloupe. Together with a small colony on the coast of South America – today’s French Guyana – and their outposts in Canada, these islands became the base of France’s overseas empire. In the same period, small groups of seagoing adventurers, acting on their own, landed on the northern coast of Hispaniola. These early settlers, not all of them French, were known as boucaniers or buccaneers because of the boucans or open fires on which they smoked meat from the wild cattle and hogs they found roaming the deserted island.

Eager to expand their colonial domains at the expense of their long-time enemies, the Spanish, the French made a move to claim territory in Hispaniola by appointing a governor for the boucaniers ’ settlements in 1665. In 1697, at the end of the European conflict known as the War of the League of Augsburg, Spain officially ceded the western third of the island to France; the remainder of the island became the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo. By this time, Europeans all across the Caribbean had realized the enormous profits to be made by establishing plantations to grow sugar. The sugar boom first took hold in some of the smaller islands of the eastern Caribbean, such as the British colony of Barbados and the French island of Martinique. By 1700, however, much of the suitable land on those islands had already been used up. Saint-Domingue, a larger colony, offered new horizons for sugar production, and an ever-increasing stream of immigrants, dreaming of wealth, arrived on its shores. In 1687, there were just 4,411 whites and 3,358 enslaved blacks in Saint-Domingue; by 1715, the figures were 6,668 whites and 35,451 blacks, and in 1730 the enslaved population had risen to 79,545. Forty years later, in 1779, there were 32,650 whites and 249,098 enslaved blacks, a figure that would nearly double by the end of the 1780s. 1

The geography of Saint-Domingue dictated its pattern of settlement. Sugar plantations needed flat, well-watered land; colonists rapidly staked out claims in the plain in the northern part of the island and later in the drier valleys between the steep mountain ranges in the west, where irrigation systems had to be built to make sugar-growing possible. The long southern peninsula of the island was the last part of the territory to be settled; harder to reach from France than the other parts of the colony, it was a center for contraband trade with the British, Dutch, and Spanish colonies to its south and west. The French administration divided Saint-Domingue into separate North, West and South provinces. Cap Français in the north and Port-au-Prince in the west were the main administrative centers; smaller cities such as Cayes, the capital of the South Province, were scattered along the coast, at points where ships could anchor and collect the products of the plantations for transport to Europe. By the mid-1700s, Saint-Domingue plantation-owners had discovered a new cash crop, almost as lucrative as sugar: coffee. Coffee trees could be grown on the slopes of the island’s steep mountains, land that was unsuitable for sugar cane. Whereas sugar plantations required large investments of money to pay for the machinery needed to crush the canes, boil their juice, and refine the raw sugar, coffee plantations were cheaper to set up and attracted many of the new colonists who arrived after 1763. Indigo, grown to make a blue dye widely used in European textile manufacturing, was another resource for small-scale plantations, and, by the end of the century, cotton-growing was also becoming an important part of the colony’s economy. In 1789 there were some 730 sugar plantations in the colony, along with over 3,000 plantations growing coffee and an equal number devoted to indigo.

Читать дальше