Not only is the high burden of private debt a deeply consequential problem in its own right, it has also been an underlying issue in several of our recent, and worst, social and economic problems. Runaway household mortgage debt growth brought the 2008 global crisis. The ensuing slow GDP growth largely resulted from the residual burden of this crisis debt, and some commentators believe it helped kindle the discontent that led to Donald Trump’s election in 2016. Since minority communities have disproportionately felt the private debt burden, it has also exacerbated the racial injustice that has only become more urgent and visible in the 2020s. High debt, along with unemployment and underemployment, has contributed to our opioid crisis. As we will see, it deepens inequality. And this debt will hobble our efforts to move the economy forward from the pandemic.

High Private Debt Is a Harmfully Consequential and Yet Largely Ignored Problem

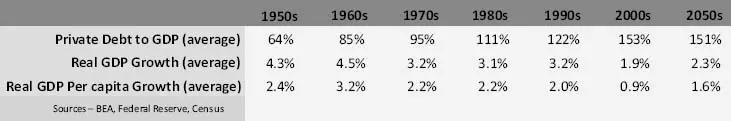

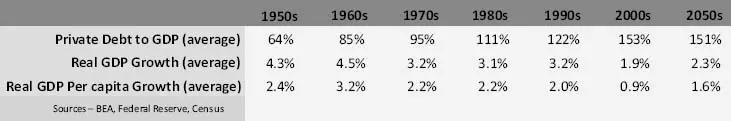

Private debt has enormous effects on American economic and societal trends – and yet it is not central to the most widely used economic forecasting models. Some economists have downplayed the adverse effect of this dramatic increase in household debt in part because they maintain that the decline in overall interest rates has offset it. To be sure, lower interest rates have helped many debtors immensely, especially mortgage holders, who have repeatedly refinanced to lower rates. But the debt service burden on households is still alarming, even accounting for lower rates. Though it has come down to some extent very recently, the “debt service ratio,” which estimates the payments consumers make on their debt in relation to their income, is still roughly 30 percent higher now than it was in the 1950s and 1960s, the two most vibrant growth decades in the post-World War II era (see Chart 6). It’s no coincidence that our highest-growth decades since World War II came when households had their lowest debt service burden. The debt payment ratio story is similar for business.

This is the vicious dynamic at the heart of working Americans’ financial distress. Higher debt curbs spending, which constrains growth. Constrained growth suppresses wages. Lower wages further constrain spending and growth. And lower wages contribute to one of the most problematic and most dire examples of private debt today as a symptom of economic dysfunction: the extent to which Americans who have seen their wages stagnate over recent decades rely on debt to meet their basic needs.

Chart 6

Some mainstream economists have also ignored or assigned little importance to private sector debt because they contend that for every borrower there is a lender, and if you add those two totals together, then debt nets to zero – and thus its aggregate effect is neutral. They maintain that high levels of debt are not a problem because it all balances out.

That logic helps explain why those economists missed the mountainous ascent of US mortgage debt that caused the 2008 crisis, a total that rose from $5 to $10 trillion in five years. The profession’s myopia relative to the 2008 crisis is now legendary, but, despite this, little has changed within orthodox economics, which continues to relegate private debt to a minor consideration.

These economists are correct on one point, however: when you consider borrowers and lenders, total debt does indeed net to zero. In fact, as we will revisit, financial assets equal financial liabilities, a well-established principle of economics, since the creation of an equal asset and liability results from the same transaction. In the case of a $1 million loan, a $1 million asset is created on the books of the bank, and a $1 million liability is simultaneously created on the books of the borrower. But although it nets to zero, private debt’s effect is anything but neutral, and would only be neutral if lenders and borrowers were the same. But lenders and borrowers are decidedly not the same, and the distribution of these debts among actual borrowers and lenders matters greatly. Private debt borrowers are a broad swath of millions of individuals and businesses, including millions of small businesses; in contrast, lenders are much more concentrated, with banks alone accounting for 33 percent of all private sector debt.

Rising debt, after the proceeds have been spent, brings the obligation to pay interest and principal that directly reduces the spending and investing of the typical borrower. However, since private sector lending is concentrated in large financial institutions and wealthy individuals, the receipt of interest payments from borrowers does not commensurately increase their spending and investing. A significant number of those lenders are already spending and investing everything they intend to, and will most likely save rather than spend much of their increased earnings from higher lending levels. To use an economist’s terminology, they have a lower marginal propensity to consume.

In other words, debt, once it reaches high levels, reduces the spending and investing of borrowers without commensurately increasing the spending and investing of lenders. This is a major reason why the effects and impact of rising debt are so uneven, and so important to study.

In fact, average-to-lower-income individuals have borne the disproportionate brunt of rapid debt growth, as is clearly shown in the proportionately greater rise of their debt in relation to their income and net worth. As such, rising debt has been a key element of rising inequality, which in the United States has increased markedly from a Gini coefficient of 0.40 in 1980 to 0.48 in 2019. The accumulation of debt is likely a consequence and a symptom of growing inequality, of course, because greater inequality means that more people have to borrow to make ends meet.

The data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances indicates the trends. From 1989 to 2019, the debt of US households with net worth in the 1 to 59.9 percentile increased by 92 percent in ratio to their incomes. In stark contrast, households in the top 10 percentile saw debt to income rise by only 18 percent .

For this bottom 59.9 percent, not only has their debt increased by 92 percent in relation to income, but their financial net worth (financial assets minus debt) has declined from 43 percent to 24 percent of their income. They have a diminished relative capacity to spend on education, investment, and other consumption. For the top 10 percent, it’s a completely different story – in fact, almost the same story told in reverse. While their debt-to-income ratio has increased by only 18 percent, their financial net worth has doubled from 158 percent to 335 percent of their income. The contrast could hardly be more stark.

As part of this, since financial assets equal financial liabilities, then more debt, whether private sector or government debt, also means more assets – or wealth. Twice the debt to GDP does generally mean twice the financial wealth (assets) to GDP – but again it is the distribution of that debt and wealth that creates issues. As these numbers illustrate, the great preponderance of that asset growth has gone to the already well-off.

These numbers show the growing divide between average and wealthy Americans. And they show just as plainly how the accumulation of private sector debt exacerbates and widens that divide.

* * *

I’ve described the context and the problem: we have soaring private sector debt that strangles growth and widens inequality, and yet is largely ignored by mainstream economics. This book makes the case for a workable and meaningful solution. It is not another broadside against government spending or a call for austerity – far from it. We need to reduce the ratio of private sector debt to GDP, which is another way of saying reduce the burden of debt on households and businesses in relation to their income. It makes the case to unburden American households mired in debt with ideas that will improve lives, reduce inequality, and bring new vigor to the economy.

Читать дальше