It must also be questioned whether the existence of two semantic spaces and the associated topographical boundary is in fact a fundamental condition for the subject of a narrative text. Even in the film, which is predestined for spatial depictions due to its visual level of reception, this is apparently not a compelling condition when one considers the genre of intimate theatre, e.g., Lumet’s 12 Angry Men , whose plot unfolds in a single jury room. This space is highly semanticized by the experiential knowledge of the recipient. The recipients know that justice is determined and administered in this space, that guilt and innocence and – in this concrete example – even life and death are decided here. But the border and the second semantic space are missing. Nevertheless, oppositional relationships can of course also be identified in this narrative, such as guilt vs. innocence, morality vs. law, racism vs. anti-racism, opportunism vs. loyalty to principles, but these are not bound to concrete spaces.

A similar problem arises when considering games, particularly the so-called “casual games” or games with less elaborate graphics and history. Especially in the early arcade games, there was often only a single game space or setting available, due to the lack of computer capacity at that time, e.g., in games like Pong , Space Invaders , or Asteroids . Since no second space can be constructed here with the corresponding oppositions, no border crossing can take place and semantization in the strict sense of Lotman is not possible. Nevertheless, these games contain narrative elements with the corresponding semantizations despite their simple graphics and limited representational potential.

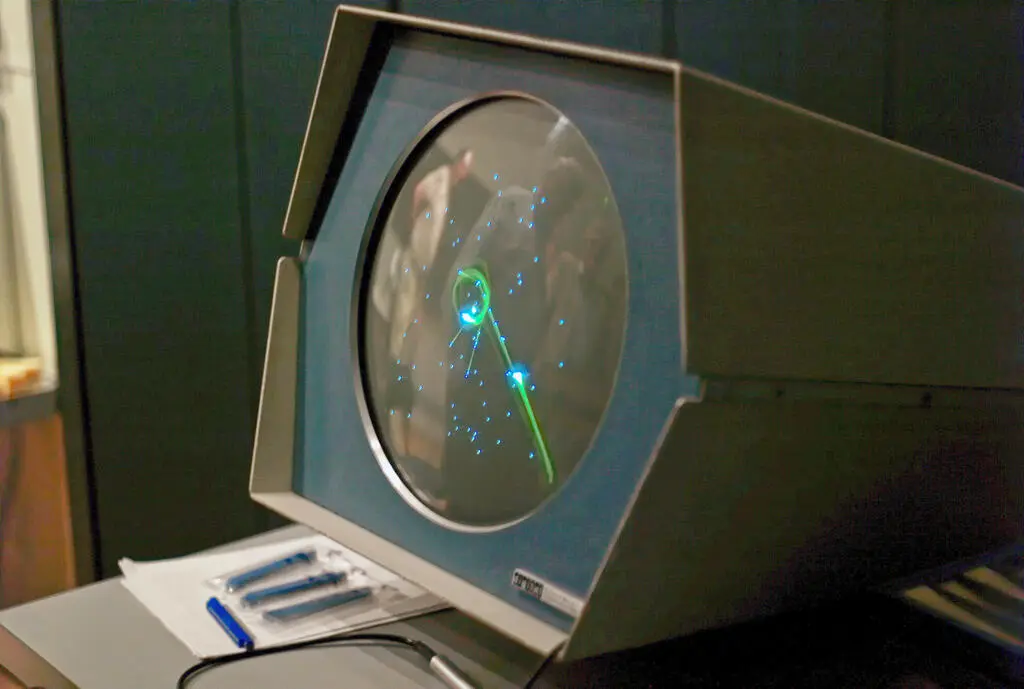

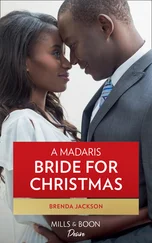

Spacewars! is considered by many to be the first computer game ever made. Here the game is shown with original source code running on a PDP-1. Image moral authors: Martin Graetz, Stephen Russell, Wayne Wiitanen, Peter Samson, Dan Edwards, Alan Kotok, Steve Piner, and Robert A. Saunders.

In one of the very first computer games, Spacewar!, programmed in 1961 by students of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the setting is the “final frontier” – the space beyond earth. This is fitting for the genre, because in all phases of the history of computer games the universe, foreign planets, space stations etc. are constantly recurring locations, be it in Galaga , Doom , or Halo . Space Invaders from 1978 is regarded as the first commercially successful space shooter and triggered the development of a whole series of games that also chose space as their setting. However, the design of the setting of these computer games is still rudimentary – in the case of Space Invaders there is nothing but four blocks behind which the player’s spaceship can seek protection. The setting is supported by other factors, such as the naming of the game and the design of the machine. Its surface is decorated with representations of aliens, rockets, planets, stars etc. to illustrate the science fiction setting of the game. With Phoenix and Galaga , the setting becomes more elaborate and already shows a star-studded galaxy in the background. It is not the richness of detail that is decisive here, but the semantization of the game space through the activation of a narrative script. Media scientist HENRY JENKINS calls this strategy of game design “evocative spaces.” He compares the game designer’s work here with the design of an amusement park, in which the attractions are often based on well-known narrative genres and settings such as the “wild west,” a fairytale environment, or a pirate ship. According to Jenkins, game designers use the same strategy. Because one falls back on the narrative competences of the recipients, the design of the world is often subcomplex and can be carried out in a suggestive or schematic way. In other words, games make targeted use of narrative archetypes or genres in order to semanticize space or integrate the game into a narrative context. The old arcade games, in particular, used this design strategy, since computer technology at that time did not allow sophisticated graphic representation. Thus, in Galaga or Space Invaders , not only does the game space contain rudimentary pixel aliens or spaceships, but also the arcade machine itself is decorated on its surface with aliens, comets, and ring planets to communicate to the recipient that this is a game in a science fiction setting, with the corresponding narrative tropessuch as alien invasion, space battles, etc. Similarly, Ghost’n Goblins features ghosts, mythical creatures, knights, and princesses, both on the machine itself and in the game space, to situate the game in the fantasy and fairytale genre and thus activate the corresponding narrative scripts, with oppositional pairs such as everyday world vs. magical world, life vs. death, noble knights vs. dangerous mythical creatures, and beautiful princess vs. ugly monster.

However, there are other possibilities of semantization in the sense of an evocative space that do not necessarily have to resort to existing narrative genres. The handheld game Candy Crush Saga is one of the most successful casual games in history. The idea of the game isn’t new in itself. It’s a so-called “match three game,” (Juul 92) which is all about combining three game pieces of the same colour or shape. Shariki is the first computer game to use this game mechanic. The game is about exchanging neighbouring orbs on the playing field in their places so that three balls of the same colour are combined horizontally or vertically, whereupon they explode and make room for new balls. The game mechanics of Shariki were often copied, e.g. in Tetris Attack , Bejeweled or Candy Crush Saga . Bejeweled was a great commercial success and is considered one of the most important pioneers for the casual games. What is the difference between Shariki and Bejeweled , which both follow the same game mechanics? Apart from minor innovations, Bejeweled stands out for its more complex and sophisticated graphics. The pieces now differ not only in color but also in shape. Furthermore, they are not only abstract shapes or orbs, but Bejeweled game pieces are shaped like jewels. Candy Crush Saga continues in the design of the game space and the game objects. The game pieces differ in colour and shape and are based on sweets. Childlike characters in cartoon style, designed like puppets, lead the player through the setting, where places like the “Pastilles Pyramid,” the “Gingerbread Glade” or the “Bubblegum Bridge” are located.

Tiffi and Mr. Toffee, two of the characters from Candy Crush Saga , with a pot full of jewels. All elements of the game conform to the childlike and colorful design. © Nguyen Hung Vu, 2013 on flickr under CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/vuhung/10405325514

In the course of the game, cut scenesintroduce the problems of the inhabitants of the country: a unicorn has lost its horn, Lemonade Lake has dried up, the Yeti has gotten caught in a sticky-sugar mass. In short: all elements of the game space and the associated world, which were not yet present in Shariki or Bejeweled , are consistently committed to a childlike, colourful, innocent design. Here, too, one can speak of a semantic space, even if at first glance no second, complementary semantic space is realized and no border crossing takes place. But in the form of obstacles, which restrict the recipient in the combination of the game pieces, an oppositional principle breaks into the world of the Candy Crush Saga : black liquorice blocks the movements of the players; colourless jelly surrounds the game pieces and makes them immobile; dark brown chocolate appears in the playing field and restricts freedom of movement. The oppositions colourful vs. colourless, mobile vs. static, light vs. dark are realized here. It should be emphasized that Candy Crush Saga does not tell a real story. Nevertheless, many narrative design elements are used, most consistently spatial semantics. It is not conclusive to determine to what extent spatial semantics are responsible for the success of the game. Nevertheless, it is striking that the same game mechanics become more and more popular with increasing semantization.

Читать дальше