“What about Swallow?” Titty had asked, the moment she had had a chance of saying a quiet word to Captain John.

But Captain Flint heard her and answered, “It’ll be a week or ten days,” he said, “before she can be afloat again. One of her timbers will have to come out, and then there’ll be at least two new planks to go in. And then they can’t launch her till she’s painted, and they can’t put paint on planks wet from steaming. A week or ten days it’ll be, at least.”

“But she really is going to be all right?”

“She’ll be as good as new.”

“Then I don’t mind being shipwrecked a bit.”

“I thought you wouldn’t,” said Captain Flint. “Who would?”

John and Titty and Captain Flint looked at each other, and Titty knew that she had been right when she had guessed that they were to be allowed to stay on.

And indeed, the best of all natives, after one look round that neat camp, felt a good deal happier. She had counted the shipwrecked even before she had stepped ashore. She had felt their clothes. She had seen with her own eyes that none of the Swallows were missing. She had known already that John was all right, because there he had been, in the boat before her, helping Captain Flint to row her down the lake. But, as for the others, she had only been told that nothing was wrong with them. Telling was hardly enough to make her quite content. After all, she knew that their ship had sunk and that they had had to swim ashore, and in spite of being the best and most sensible native anyone ever knew, she was very pleased to be here and to make sure for herself (by kissing and rubbing noses, for example) that not a single one of the ship’s company had been quite enough of a duffer to be drowned.

“It’s a good thing you hadn’t got the ship’s baby aboard when you were wrecked,” she said at last.

Able-seaman Titty was playing with the ship’s baby. She looked up at once.

“I expect she was on board. It wouldn’t be fair if she wasn’t. You were, weren’t you, Bridgie? And when the ship went down she was put on a raft, and the raft floated away in a current like the Gulf Stream, and we should never have seen her again if you hadn’t happened to be coming along in your canoe and found the ship’s baby sailing away on a raft by herself.”

“That must have been it,” said the best of all natives. “She was sailing away on the raft and had nothing with her to eat but one doughnut, and even that she was sharing with a gull who had perched on her raft and looked hungry.”

“Well, I’m glad you found her,” said the able-seaman.

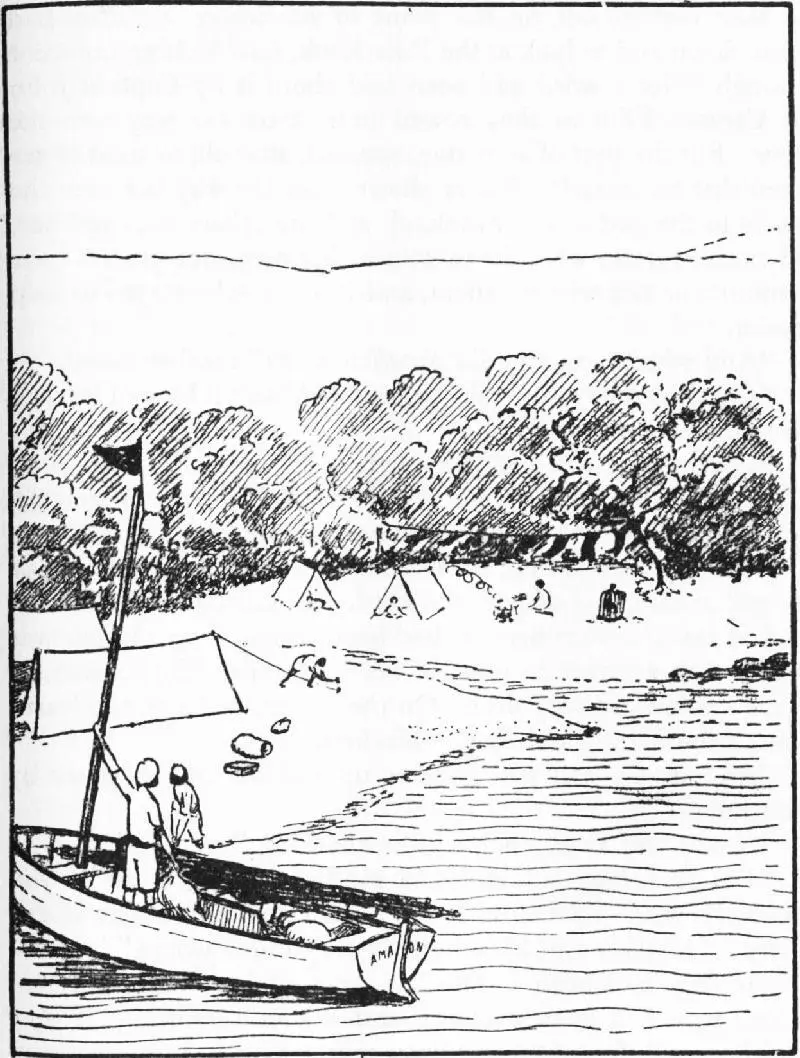

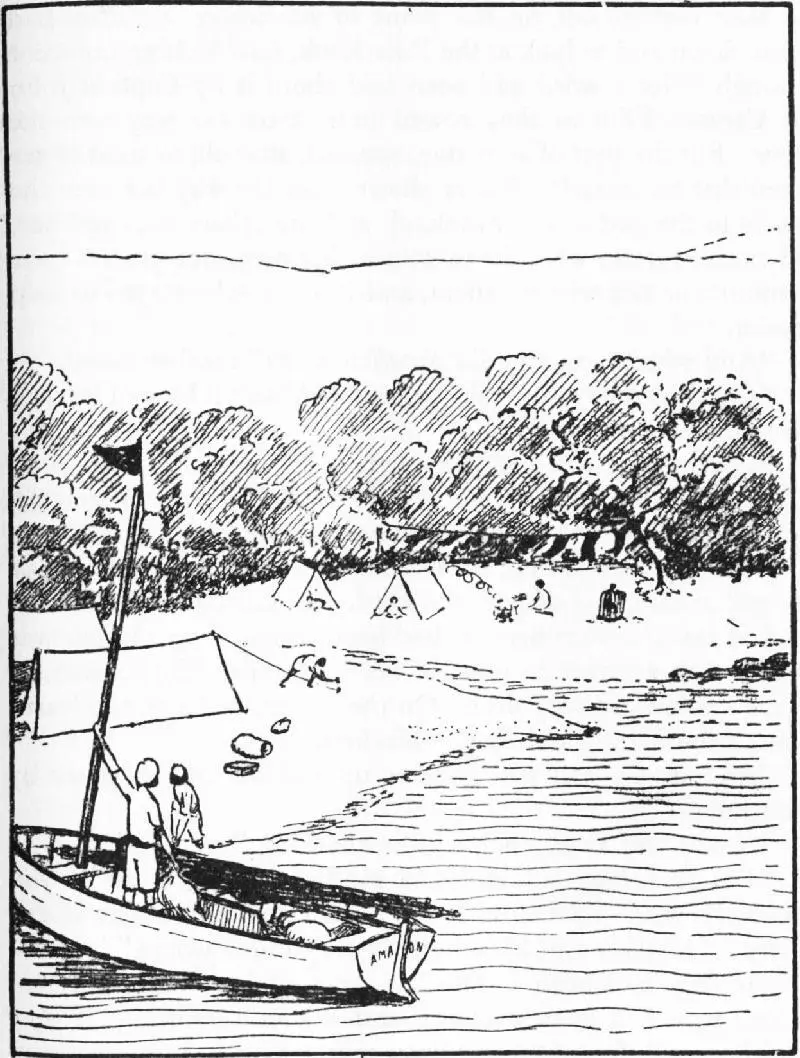

IN HORSESHOE COVE

IN HORSESHOE COVE

It was chiefly Roger, among the shipwrecked, who wanted to take mother out on the point to see where Swallow had gone down and to look at the Pike Rock, now looking innocent enough. Not a word had been said about it by Captain John or Captain Flint as they rowed past it on the way into the cove. But the best of all natives seemed, after all, to want to see even that for herself. Roger showed her the way out over the rocks to the end of the headland, and the others followed her, all except Susan, who, for reasons of her own, was glad to have a minute or two without them, and Bridget, who stayed to help Susan.

“And where, exactly, did Swallow sink?” mother asked.

“Close by the rock,” said Roger. “Wasn’t it lucky I learned to swim last summer?”

“I suppose it was,” said mother.

“Well if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have been able to get far enough to catch hold of the rope and be hauled out,” said Roger.

Then, by questioning, she learned something of how they had all got ashore, and of how the kettle and saucepan and ballast, and at last Swallow herself, had been brought up. Roger was ready with answers to most of her questions. Titty answered some. John said very little. On the whole, perhaps, she learnt most from Nancy and Peggy Blackett.

“And in the end you got her up and out of the water by yourselves?”

“Nancy and Peggy helped like anything,” said John.

“I’m sure they would,” said mother. “I think all of you did very well. And now I don’t want to think about it any more. Things might have been so very much worse.”

“If they had been a different crew, ma’am,” said Captain Flint, who had been listening and saying nothing—“if they had been a different crew, things might have been a great deal worse. But I gather there was no sort of panic, except, perhaps, among the spectators on shore.”

“I only squeaked once,” said Peggy indignantly, “and anybody might have squeaked.”

“You see, ma’am,” said Captain Flint, “there was no panic, even on shore. Taking it all round it seems to have been a shipwreck to be proud of.”

“Well, I’d rather they didn’t do it again,” said the best of all natives.

“We aren’t going to,” said John.

Just then there was the cheerful note of the mate’s whistle, and they heard Bridget calling from the camp that tea was ready.

Susan had had everything nearly ready before ever Nancy had sighted the rowing boat in the distance. The kettle had been on the very edge of boiling, and everything else was being kept cool and out of the way until the last minute, in the store tent. Now the kettle had boiled, tea had been made, and while the others were talking shipwreck at the point, Susan had folded the old ground-sheet in two (the one from which they had cut a patch to put on Swallow’s wound) for a table-cloth, so that when they came back after hearing the whistle and Bridget’s calling, they found a tea worth looking at, with the lids of biscuit tins piled high with slices of fried seed-cake (it had been dried by Peggy and it really did seem to taste all right) and sandwiches of bunloaf, marmalade and butter. Usually on the island it had been found best to carve one very thick slice for each explorer and to put the butter on at the last minute to avoid the sort of accident that so easily happens to anything when one side of it is buttered, and it is not eaten at once. But to-day, thin, buttered slices, and small sandwiches neatly arranged in pyramids, suggested an orderly quiet world in which nothing could ever go wrong.

“I’ve said it before, and I say it again,” said Captain Flint, when he saw what Susan had done, “there never was an expedition that had a better mate.”

Everything was working out just as he had thought it might. Nobody could be much worried about shipwrecks that were already over when the shipwrecked mariners asked them to sit down to such a tea as that. Still, not even Roger thought it quite safe to ask if they were to be allowed to stay. But when tea was over, mother, after saying what a good tea Susan and Bridget had made, let them know what the answer was to the question that had been in everybody’s mind.

“And now,” she said, “if you really don’t want to come back to Holly Howe and get on with the holiday tasks, I suppose I must go and talk to this Mary Swainson.”

“We can do holiday tasks anywhere,” said John.

“If you do a holiday task indoors,” said Titty; “it isn’t really a holiday task. It might just as well be a school one.”

Captain Flint carried Bridget on his shoulder, and they showed the best of all natives the way up the stream and so to the cart-track, and out through the trees to the road, and there they saw Mary Swainson herself talking to a young man sitting on a big roan cart-horse.

“It’s the woodman,” said Titty, “the one we saw leading the three horses and the log when Roger and I were exploring.”

Читать дальше

IN HORSESHOE COVE

IN HORSESHOE COVE