Chapter XIV. Settling In

Chapter XV. Life in Swallowdale

Chapter XVI. Surprise Attack

Chapter XVII. Later and Later and Later

Chapter XVIII. Candle-Grease

Chapter XIX. No News

Chapter XX. Welcome Arrow

Chapter XXI. Showing the Parrot His Feathers

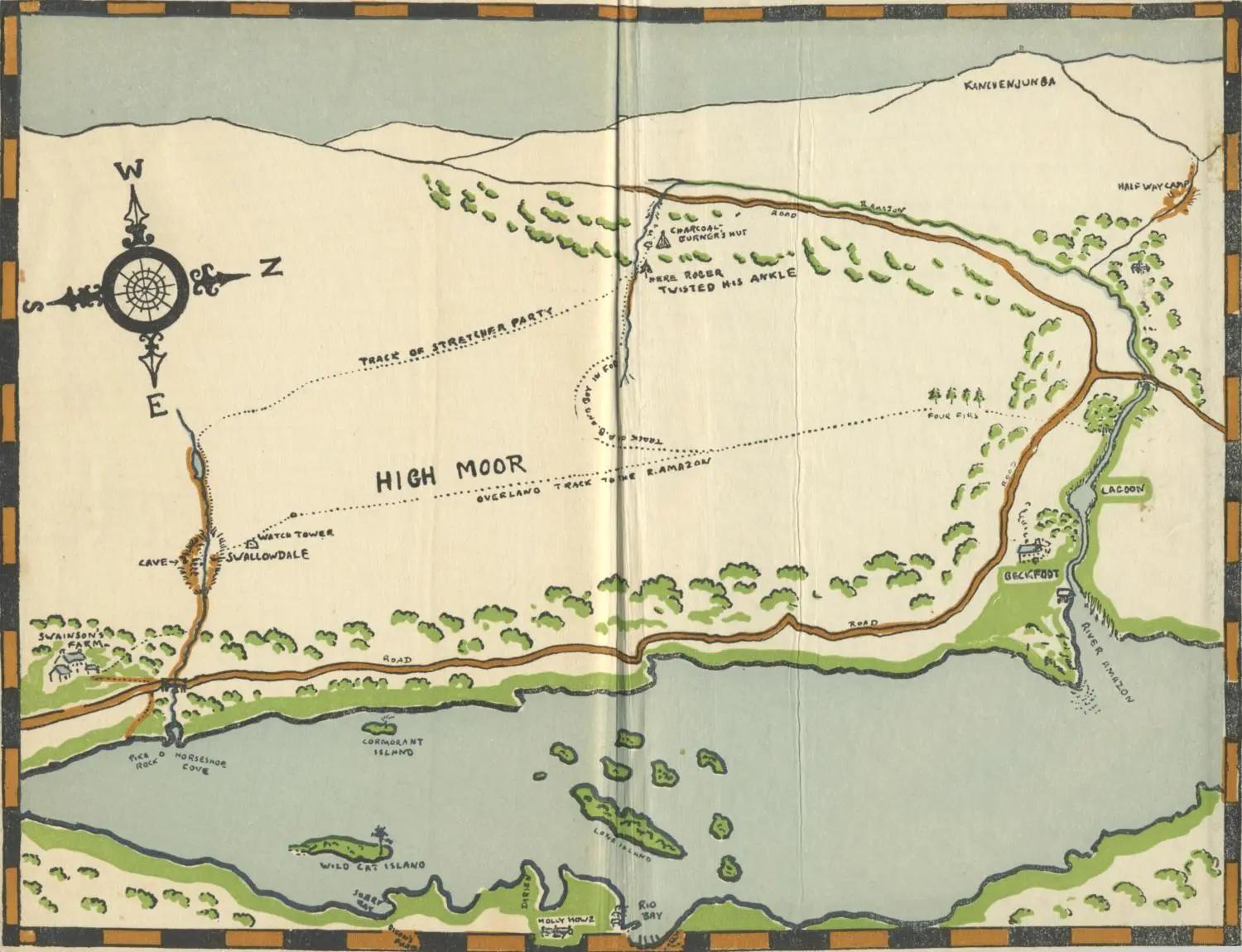

Chapter XXII. Before the March

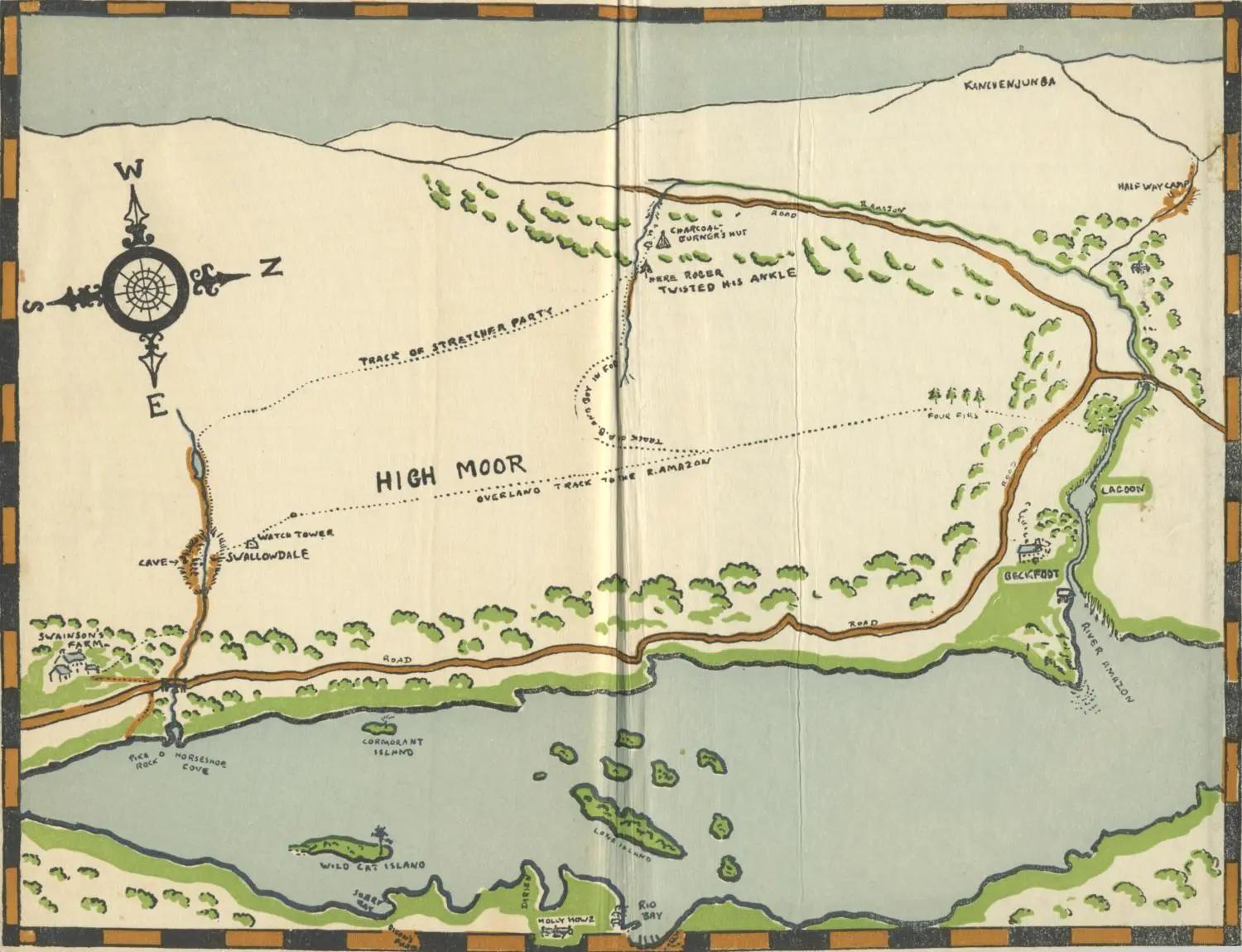

Chapter XXIII. Overland to the Amazon

Chapter XXIV. The Noon-Tide Owl

Chapter XXV. Up River

Chapter XXVI. The Half-Way Camp

Chapter XXVII. The Summit of Kanchenjunga

Chapter XXVIII. Fog on the Moor

Chapter XXIX. Wounded Man

Chapter XXX. Medicine Man

Chapter XXXI. Wigwam Night

Chapter XXXII. Fog on the Lake

Chapter XXXIII. The Empty Camp

Chapter XXXIV. Stretcher-Party

Chapter XXXV. The Race

Chapter XXXVI. Wild Cat Island Once Again

Footnote

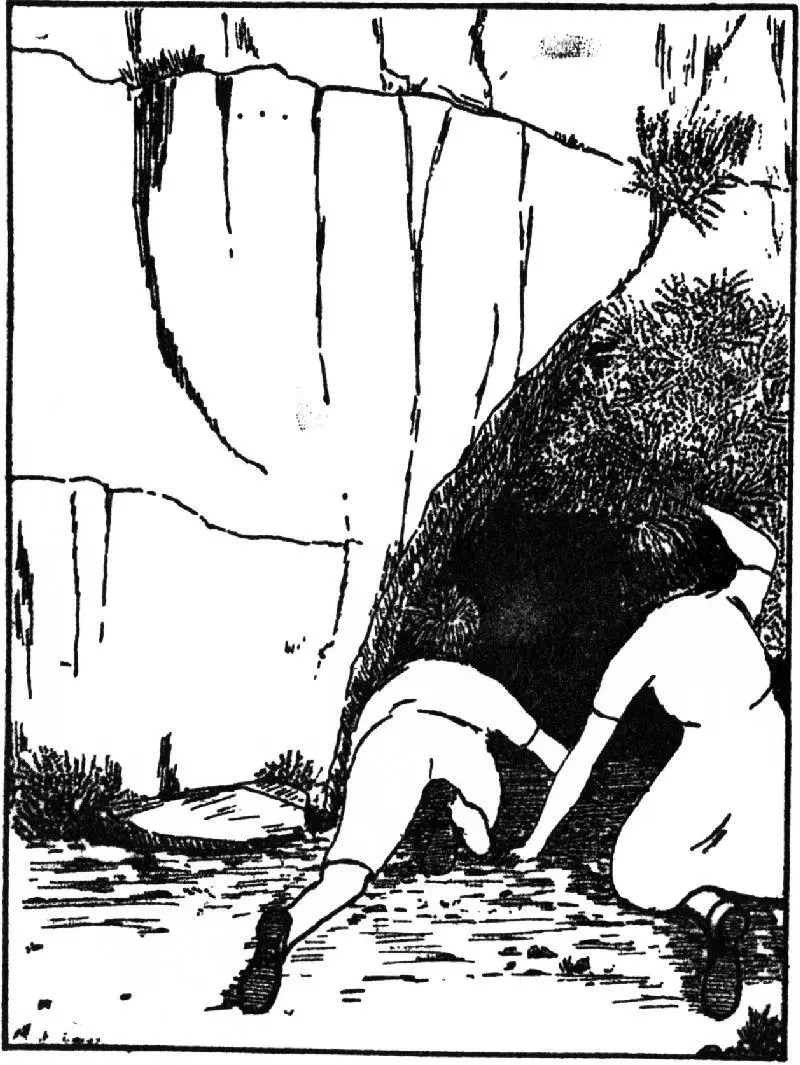

DISCOVERY

DISCOVERY

TO ELIZABETH ABERCROMBIE

Chapter I.

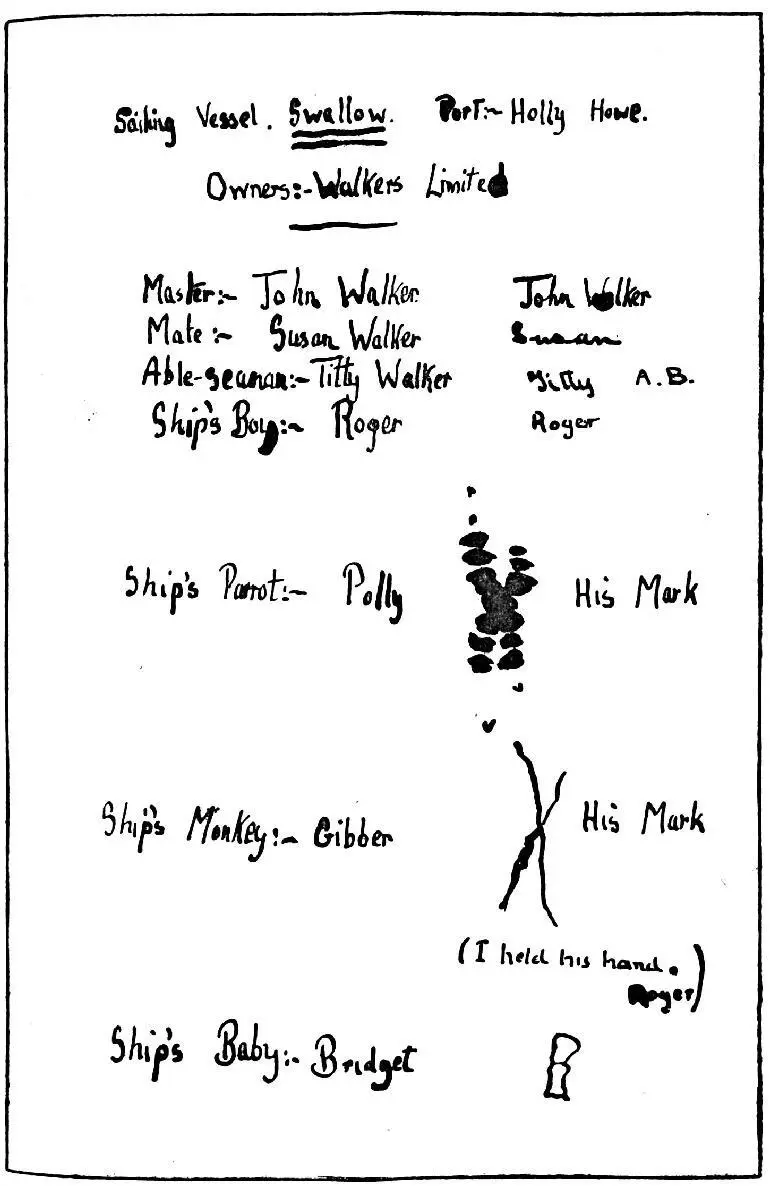

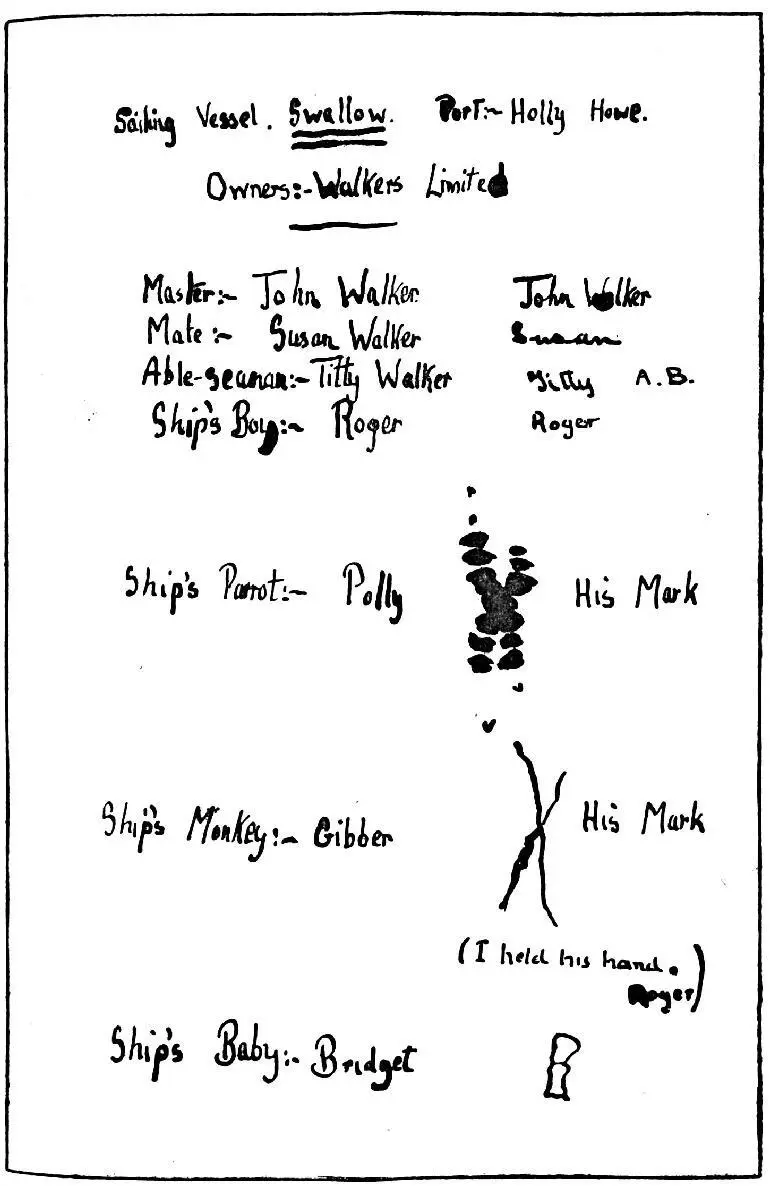

The Swallow and Her Crew

Table of Contents

“A handy ship, and a handy crew,

Handy, my boys, so handy:

A handy ship and a handy crew,

Handy, my boys, AWAY HO!”

Sea Chanty

“Wild Cat Island in sight!” cried Roger, the ship’s boy, who was keeping a look-out, wedged in before the mast, and finding that a year had made a lot of difference and that there was much less room for him in there with the anchor and ropes than there used to be the year before when he was only seven.

“You oughtn’t to say its name yet,” said Titty, the able-seaman, who was sitting on the baggage amidships, taking care of her parrot who, for the moment, was travelling in his cage. “You ought to say ‘Land, Land,’ and lick your parched lips, and then afterwards we’d find out what land it was when we got a bit nearer. We might have been sailing about looking for it for weeks.”

“But we know already,” said the look-out. “And anyway there’s land all round us. I’ll be able to see the houseboat in a minute. There it is, just where it used to be. But (his voice changed) Captain Flint’s forgotten to hoist a flag.”

The little brown-sailed Swallow with her crew of five, including the parrot, had left Holly Howe Bay, and was now beating across the open lake that stretched away to the south between wooded hills, with moorland showing above the trees and, in the distance, mountains showing above the moorland. A whole year had gone by. August had come again. The Walkers had come up from the south yesterday. John, Susan, Titty and Roger had been at the window with the parrot as the train came into the little station, thinking that their old allies, Nancy and Peggy Blackett, would be on the platform to meet them, perhaps with their mother, or with Captain Flint, that retired pirate, who lived in the houseboat in Houseboat Bay and was really Mr. Turner, Nancy’s and Peggy’s Uncle Jim. But no one had been there. All the morning, while mother, little Bridget and nurse had been unpacking boxes and settling into the old farmhouse at Holly Howe and they had been down at the boathouse loading Swallow for her voyage to Wild Cat Island, they had been sending scouts up to the high ground, to look up to the northern part of the lake to see if a little boat about the size of Swallow had come out of the Amazon River, where the Blacketts had a house, away up there towards the Arctic, under the great hills. Every other minute they had been looking for the little white sail of the Amazon at the mouth of the Holly Howe Bay, expecting to hear Captain Nancy’s jolly shout of “Swallows and Amazons for ever!” and to see Mate Peggy hoisting the Jolly Roger to the masthead. Then the Swallow and the Amazon would sail down to Wild Cat Island together, calling on their way on the houseboat to say, “How do you do” to Captain Flint. Everything would be just as it had been last year. But they had seen no sign at all of their allies and when afternoon came they could wait no longer. Mother and Bridget had gone off to the little town to buy stores for them and were going to bring the stores down to the island in the native rowing boat from Holly Howe. Whatever happened, they had to get the camp ready before mother arrived, so that she could see that all was well for the first night. It was no good waiting for those Amazons. Nancy and Peggy were probably in the houseboat with Captain Flint. Or, more likely still, they were already on Wild Cat Island, plotting either a welcome or an ambush. With Nancy you never really knew. So the four explorers had set sail. The thing they had been planning for a year was at last beginning. It had indeed begun, for once more they were afloat in Swallow, and sleeping at home in beds had already come to an end.

“I do think he ought to be flying his flag,” said Roger, the look-out.

“Perhaps he didn’t think we’d be sailing so soon,” said Titty, the able-seaman, who was resting a telescope on the cage of her parrot, and looking through it at the distant houseboat.

“He’ll hoist his flag all right when he sees us coming,” said Susan the mate.

John, the eldest of the four of them, said nothing. He was too busy with the sailing, now that Swallow had left the shelter of the bay and had begun to beat down the lake against the southerly wind. He was looking straight forward, feeling the wind on his cheek, enjoying the pull of sheet and tiller and the “lap, lap” of the water under Swallow’s forefoot. Sometimes he glanced up at the little pennant at the masthead, a blue swallow on a white ground (cut out and stitched by Able-seaman Titty), to be sure that he was making the most of the wind. It takes practice to know from the feel of the wind on your cheekbone exactly what your sail is doing, and this was the first sail of these holidays. Sometimes he glanced astern at the bubbling ribbon of Swallow’s wake. At the moment, it did not seem to matter whether Captain Flint was flying a flag from the masthead of his houseboat or not. To be on the lake again and sailing was enough for John.

Mate Susan, too, did not mind that there was no flag on the old houseboat. She had had a tiring time the day before, looking after her mother and Bridget and nurse and the others and all the small luggage during the long railway journey from the south. She always took charge on railway journeys and was always very tired next day. But nothing had been forgotten, and the number of things that would have been forgotten if Susan had not remembered them was very great. And then, this morning, there had been lists of stores to make out and check, besides the stowage of cargo in Swallow. So Susan was resting and happy, glad that for the moment everything was done that she could do, glad no longer to hear the din of railway stations, and glad, too, not to have to listen to strange voices in that din to make sure that they ought not to be changing trains.

Even Able-seaman Titty was less disturbed than Roger at seeing no flag on the houseboat’s stumpy little mast. She had so much else to think about. At one moment she felt that this was still last year and that they had never left the lake and gone away. All that long time of lessons and towns was as if it had never been. And then, the next moment, it was just that time that seemed real, and she could not believe that it was the same Titty who had had such awful troubles with her French verbs who was now once more the able-seaman, sitting in Swallow with the parrot cage and the knapsacks and the stores, looking back at the Peak of Darien from which she had first seen Wild Cat Island, and looking down the lake at the island itself, sketches of which with its tall lighthouse tree had filled, almost without her knowing how they came there, the two blank pages at the end of her French Grammar. This feeling of being two people at once in a jumble of two different times made her a little breathless.

Читать дальше

DISCOVERY

DISCOVERY