The crew had been rewarded by getting permission from their captain to go ashore. They had landed on the island near which they were anchored. They had bathed from it, and made a fire on the shore, not for cooking, because they had brought no kettle, but because landing on an island without making a fire is waste of an island. They had drunk half their milk and eaten half their rations. Then while John stayed on the island he had sent the mate and the boy to sail in to Rio, to buy stores. They had bought a shilling’s worth of the sort of chocolate that has almonds and raisins in it as well as the chocolate, and so is three sorts of food at once. They had come back. They had visited several other islands, and had an unpleasant meeting with some natives on one of them, who pointed to a notice board and said that the island was private, and that no landing was allowed.

Only once Captain John had thought he had seen one of the Amazons moving in the heather on the promontory. But he could not be sure without the telescope. It might have been a sheep. The wait all through the afternoon and early evening had been long and tiring, and though there had been plenty to look at in the steamers and motor boats and rowing skiffs of the natives, they had seen no sails except those of large yachts far away up the lake. For the first time in their lives all three of them had wished to hurry the sinking sun upon its way.

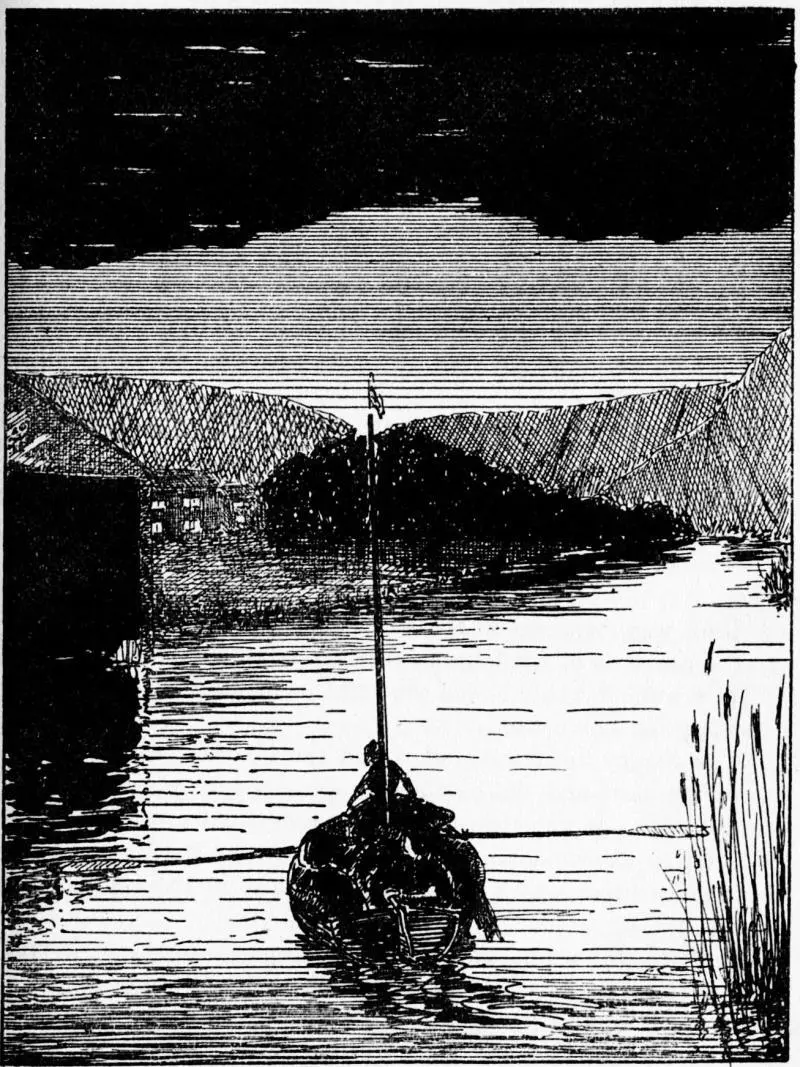

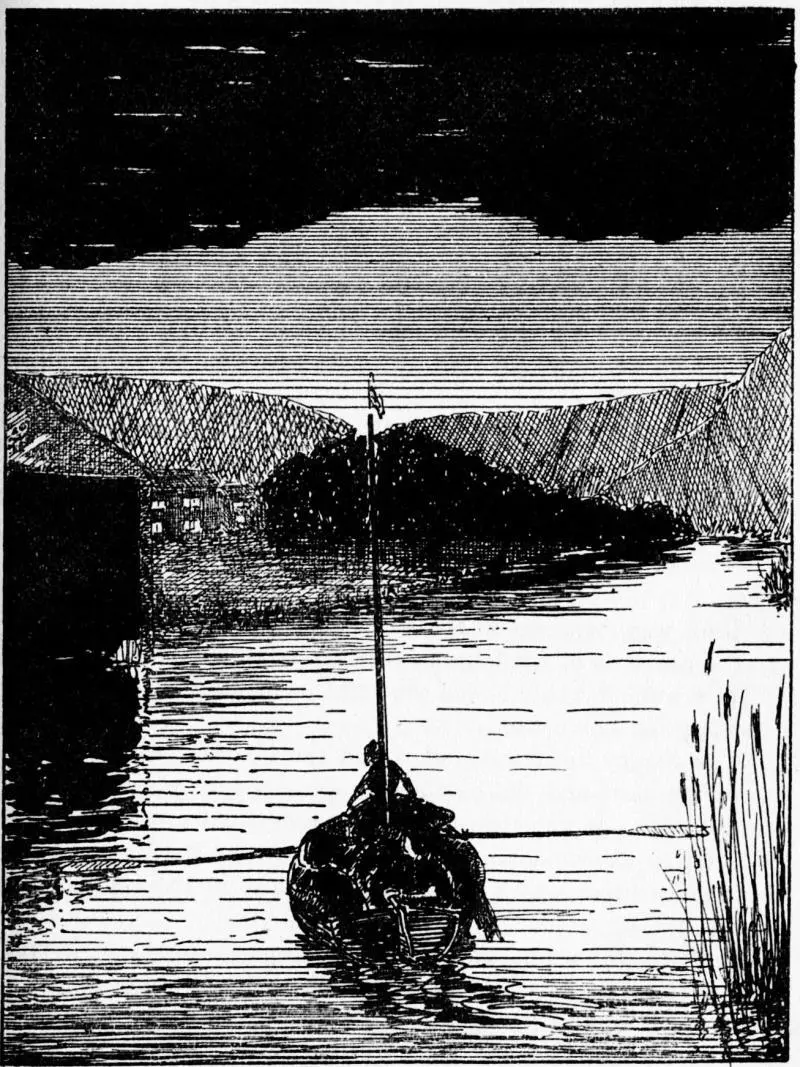

Now, at last, the sun had set. Twilight was coming on. There was no wind, for the wind had gone with the sun as it so often does, and they were beginning to be afraid that the dark would come too soon for them. All was astir in the Swallow.

The mast was unstepped, and laid on the thwarts so that it stuck out over the bows. There was room for it in the ship, for it was a few inches shorter than Swallow was long. But to stow it all inside it had to lie straight down the middle, so that it was very uncomfortable for anybody who was rowing.

“Anyway, why shouldn’t she have a bowsprit?” said John. “Besides, it’s only for a short time.”

Roger rowed. John was looking at the chart in the guide book. Susan steered.

“Pull with your back,” she said, “don’t bend your arms till the end of the stroke.”

“I’m pulling with all of me,” said Roger, “but I’ve got too many clothes on.”

“He’s making a fair lot of noise and splash,” said the captain.

“He’ll be tired before we get near enough for it to matter,” said the mate.

“No I won’t,” said Roger.

Slowly they moved across to the western shore. No one could row Swallow fast. It was growing dusk. Already the hills were dark, and you could not see the woods on them. It began to seem that after waiting so long because it was too light, they were going to fail after all because it would not be light enough.

“Look here, Susan,” said John, “I think I’d better row.”

But just then a line of ripples crept over the green and silver surface of the smooth water.

“Thank goodness,” said Captain John. “Here’s the wind again, and it’s the same wind. Sometimes it changes after sunset, but this is still from the south.”

The ripples grew as the south wind strengthened.

“It’ll be against us on the way home,” said the mate.

“There’ll be no hurry then,” said John.

“What about sailing?” said Roger. “But I’m not tired.”

“It isn’t as if Swallow had a white sail,” said Captain John. “They’ll never see the brown one in this light, especially if we hug the shore. And we can with this wind. Yes, Mister Mate. Tell the men to bring the sweeps aboard.”

“Easy,” said the mate. “Bring the sweeps in.”

Roger stopped rowing and lifted first one oar and then the other from the rowlocks and laid them quietly down.

“Keep her heading as she is,” said Captain John.

“As she is, sir,” said the mate. In a calm things go anyway in a sailing ship, but a little wind sharpens them up at once.

John stepped the mast as quietly as he could. He hooked the gaff to the traveller and set the sail. There was a little west in the wind and the boom swung out on the starboard side.

“She’s moving now like anything,” said the boy.

“I don’t want to get there too soon,” said John, “but I do want to get into the river while it’s still light enough to see but late enough for the pirates to be off their guard and feasting in their stronghold.”

“Peggy said they had supper at half-past seven,” said Susan.

“Well it’s ages after that now,” said John. “I should think we are all right.”

Here and there on the shores of the lake lights twinkled in the houses of the natives. Astern of them, over the tops of the islands, there was a huge cluster of lights in Rio Bay. But it was not quite dark yet, though the first stars were showing.

Swallow was sailing fast and in a very little time they were abreast of the promontory, and could see its great dark lump close to them.

“We must lower sail now,” said the captain.

He lowered the sail himself. He could not trust even Susan to lower it without making a noise. Then he wetted the rowlocks so that they would not squeak.

The Swallow drifted on past the point. Beyond the promontory was a wide bay with deep beds of rushes on either side of it. Somewhere at the head of the bay was a house with lights in its windows. The lights, reflected in the water, showed exactly where was the opening of the river mouth between the reeds. A moment later they lost sight of the reflections and knew that they had drifted too far.

“Now, Mister Mate,” whispered John. “Will you row, as quietly as ever you can? Roger goes forward to keep a look-out. Don’t shout if you see anything. Just tell the mate under your breath.”

“What about the mast?” asked the mate.

“If they’re watching, they’ll see the ship and know her, anyhow,” said Captain John. “If they’re not watching, the mast doesn’t matter. If they are in the house in those lighted rooms, they won’t be able to see anything at all out here. I’m sure we’ve done them, if we can find the boathouse. They’d have challenged us long before this if they’d seen us.”

The mate rowed with slow, steady strokes. Her oars made no noise at all. They slipped in and out of the water without a splash. Swallow was in smooth water now, sheltered by the high ground of the promontory. John steered till he could see the lights of the house reflected in the river. That was the opening in the reeds. He steered towards it. Presently there were tall reeds on either side of them. They were in the Amazon River.

“The boathouse is somewhere on the right bank,” whispered John. “That’s our left. Tell Roger to keep a look-out to port.”

Suddenly there was a splash in the reed beds, followed by a loud quack.

“What’s that?” said Susan, startled.

“Duck,” said the captain.

Susan rowed on.

There was a whisper from the look-out. “There it is. I see it.”

“Where?” whispered the mate, looking over her shoulder.

“There,” said the boy.

High above the reeds, not far ahead of them, on the right bank of the river rose the black square shape of a large building.

“That’s it,” whispered the captain.

“The boathouse,” said the mate.

“Quiet.”

“ ’Sh.”

The boathouse stood deep in an inlet among the reeds. Captain John steered towards it.

“Easy all!” he whispered. There was dead silence on the river as the Swallow drifted on. There was a noise of music in the house with the lights in it.

“Captain Nancy said the boathouse had a skull and cross-bones on it,” whispered Captain John.

THE ENEMY’S BOATHOUSE

THE ENEMY’S BOATHOUSE

Читать дальше

THE ENEMY’S BOATHOUSE

THE ENEMY’S BOATHOUSE