“Did you really swim?” said the mate.

“Aye, aye, sir,” said the boy. “Three kicks, not touching anything. Come down, and I’ll show you.”

“Can’t now,” said the mate. “You dry yourself and help to get the breakfast. We’ll bathe again in the middle of the day, and you can show me then. Now, skip, and get the captain’s chronometer out of his tent.” He got it. “Hi!” she called, as he capered off again. “Take the milk-can down to the Swallow. It’s time someone went across to the farm.”

John and Titty went across to the mainland to fetch the milk from Mrs. Dixon’s. Roger and the mate between them had breakfast ready when they got back.

After breakfast John called a council for a second time.

“It’s about Captain Flint again,” he said.

“Do let’s go and sink him,” said Titty.

“Shut up, you fo’c’sle hands,” said the mate.

“It’s not altogether about his letter,” said Captain John, “it’s about what the charcoal-burners said. You see, there’s no wind. We shan’t see the Amazons to-day, so we can’t give them the message. That means that the houseboat man . . .”

“Captain Flint . . .” said Titty.

“Able-seaman Titty, will you shut up?” said the mate.

“It means that he won’t know what the charcoal-burners wanted him to know. Don’t you think we ought to tell him without waiting for the Amazons? You see,” he went on, “it’s all native business. It’s got nothing to do with us, even if he is a beast, and thinks we’ve been touching his houseboat. We haven’t and we’ve got an alliance against him with the Amazons, but all the same, about this native business, it wouldn’t do not to tell him. We were to have told the Amazons. They’re not here, so I think we’d better tell him ourselves.”

“Would the Amazons tell him?” asked Susan.

“I’m sure they would. They wouldn’t like anyone else to break into his houseboat, specially when they’re going to break into it themselves. They’ve broken into it before, when they took the green feathers. I’ve been thinking about it, and I’m sure they wouldn’t like natives breaking into it. I’m going to tell him.”

“You could declare war on him at the same time.”

Captain John cheered up. “Yes,” he said, “so I could. The Amazons couldn’t help being pleased with that. Yes. I’ll tell him what the charcoal-burners said. That’s got nothing to do with us. It’s native business. Then I’ll tell him we haven’t ever been near his boat. Then I’ll tell him that we declare war on him and are going to do everything we can against him.”

“Let him look to himself,” said Titty. “That’s the proper thing to say.”

“We ought to give the message, anyhow,” said Susan. “We promised we would, and I tied a knot in my handkerchief and showed it to the charcoal-burners. That’s a double promise. Shall we all go?”

“I’ll go by myself,” said Captain John, “then he can’t think it’s an attack. He’ll know it’s only a parley.”

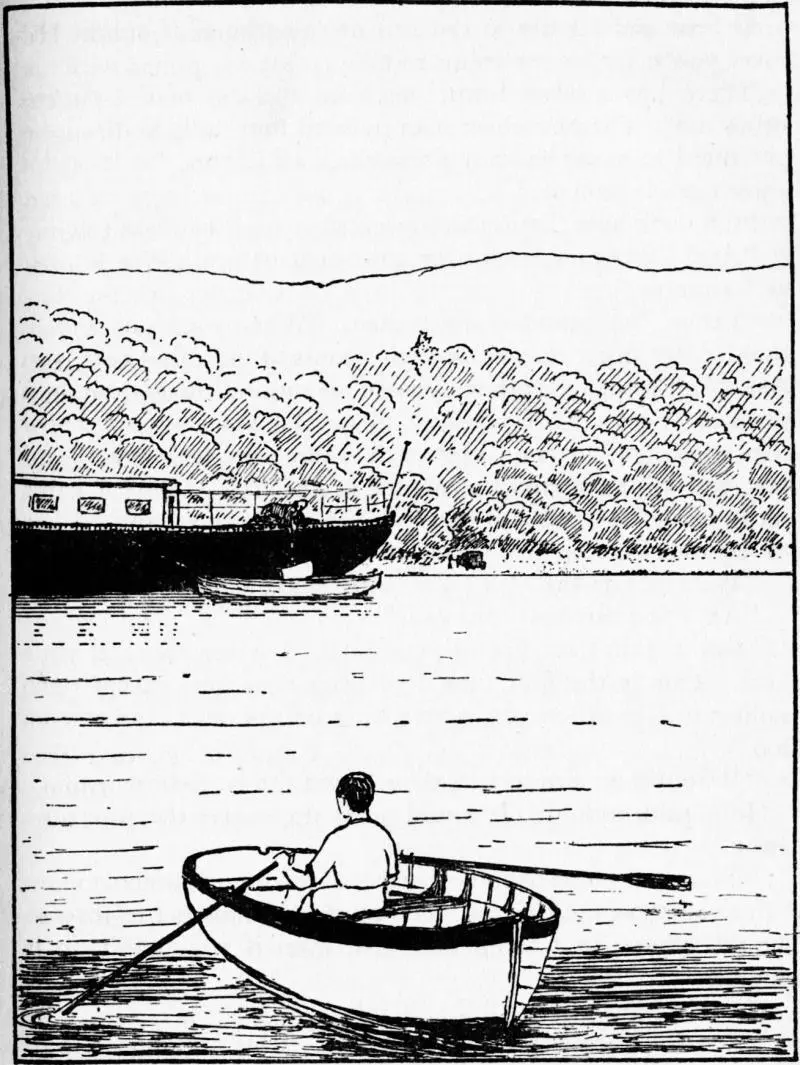

And so it happened that on the second day of the calm Captain John once more took the mast and the sail out of Swallow. Only this time he rowed north instead of south, and he rowed alone. He did not like going, because he was worried about what the Amazons would think, and after all it was their message. Also he did not like going to deliver a message to an enemy who had stirred up the natives against them so unjustly. He remembered what Mrs. Dixon had said. Further, he held the houseboat man for a bad kind of enemy because he had come to the camp while the Swallows were all away. Still, there was the message, a native message. It would be more uncomfortable not to deliver it than to deliver it. It would soon be done anyway. Captain John waved as he passed the camp, and then settled down to work, rowing steadily, navy stroke, with a smart jerk as he lifted his oars from the water.

It did not take him long to reach the southern point of Houseboat Bay. He rounded it, looked over his shoulder to see that he was heading straight for the houseboat, and then looked over the stern of Swallow to the opposite shore of the lake. Directly over the stern on the far side of the lake there was a white cottage. On the hillside above the cottage was a group of tall pines. He chose the one that seemed exactly over the chimney of the white cottage. The cottage and the tree would be like the marks leading into the harbour on Wild Cat Island. So long as the tree was directly over the cottage and over the stern of the Swallow, he knew he would be heading as he was, straight for the houseboat. He made it a point of honour not to have to look round to make sure of his direction.

He plugged away at the oars again, navy stroke, not hurrying but keeping his timing as regular as a clock. It was another point of honour that the oars should not splash when they went into the water. Yes, he was rowing quite well. But meanwhile he was thinking of what he should say to the houseboat man. The message was native business, not real, so that it would not do to call the houseboat man Captain Flint. That would come afterwards with the declaration of war. He would have to begin by calling him Mr. Turner. Then there was that beastly note. That would come in the Captain Flint part of the talk. Yes. The first thing to do would be to give the message from the charcoal-burners. Then, when the native business was done with, he could talk about the note, and declare war.

Suddenly he heard the squawk of a parrot and a shout, quite close to him.

“Look out! Where are you going to?”

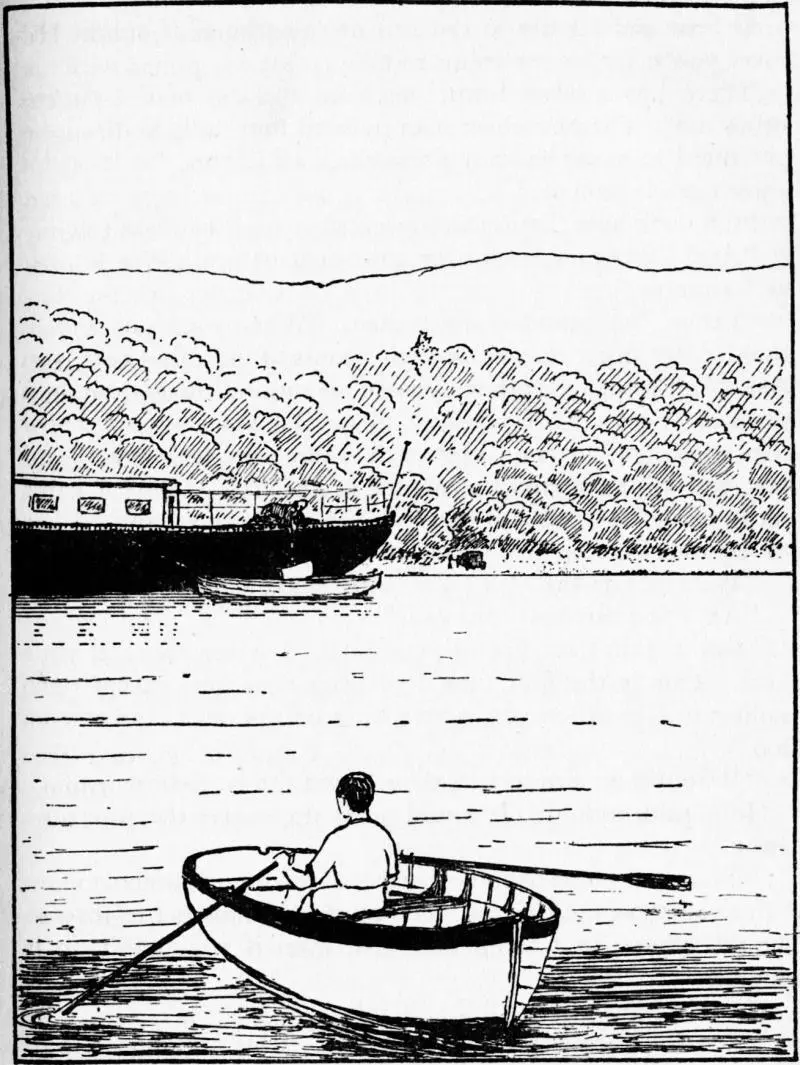

Captain John backwatered sharply, and looked round. He was a dozen yards or so from the houseboat. He pulled with his right, and backwatered with his left, so as to turn Swallow round. Then, backwatering gently with both oars he brought her, stern first, nearer to the houseboat.

CAPTAIN JOHN BACKWATERED

CAPTAIN JOHN BACKWATERED

The houseboat man was on deck, lowering a large suitcase into a rowing boat that lay alongside. In the bows of the rowing boat was a large cage with the green parrot in it. The houseboat man, in very towny clothes, was lowering his suitcase into the stern. A motor car was waiting on the road which ran close to the shore at the head of the little bay. It was clear that the parrot and the houseboat man were presently going away.

John was just going to say “Good morning,” or something like that, but the houseboat man spoke first.

“Look here,” he said, “did you find a note I left in your camp yesterday?”

“Yes,” said John.

“Can you read?”

“Yes.”

“Did you read it?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I meant what I said in it. I told you to leave the houseboat alone, and here you come the very next morning. Once is quite enough. Just you lay to your oars and clear out. Fast. And don’t come here again.”

“But . . .” said John.

“And if you’ve got any more of those fireworks, the best thing you can do with them is to drop them in the lake. If you must let them off, let them off in a field.”

“But I haven’t,” said John.

“That was the last one, was it? Well, it did enough damage. How would you like someone to come and let off a firework in your boat and set fire to the sail or something? Look at the mess you made of my cabin roof.”

There was a large burnt patch on the top of the curved cabin roof. The houseboat man pointed to it indignantly.

“But I’ve never had any fireworks,” said John, “at least not since last November.”

“Oh, look here,” said the houseboat man, “that won’t do.”

Читать дальше

CAPTAIN JOHN BACKWATERED

CAPTAIN JOHN BACKWATERED