“It ain’t as if Black Jake don’t know how to get there,” said Bill, talking it over with the others. “And if he gets there first we’d best go somewhere else.”

So, though the Wild Cat was no racing clipper like the Thermopylae, but only a little schooner with pole masts and rather small sails for her size, everybody agreed to waste no time that could be saved. Captain Flint took the topsails off her every night, because, he said, in these waters, and with uncertain winds, you never knew when you wouldn’t be jolly glad not to have to take them off in a hurry in the dark. But at earliest dawn he set topsails again. Everybody did the best they could for the little schooner, and the worst that ever John or Nancy or Bill said of each other was to point out that whoever of them was at the wheel had put a waggle in her wake.

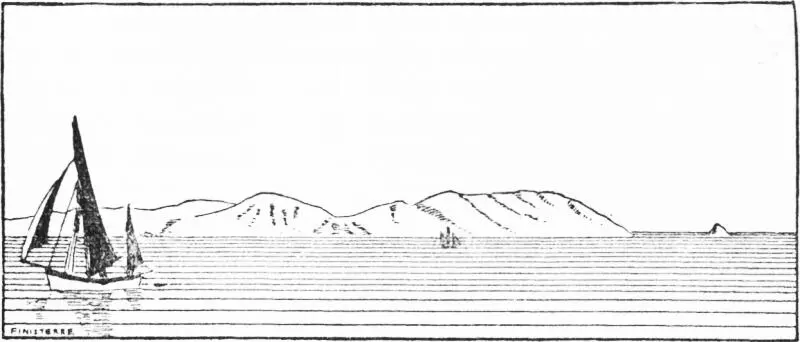

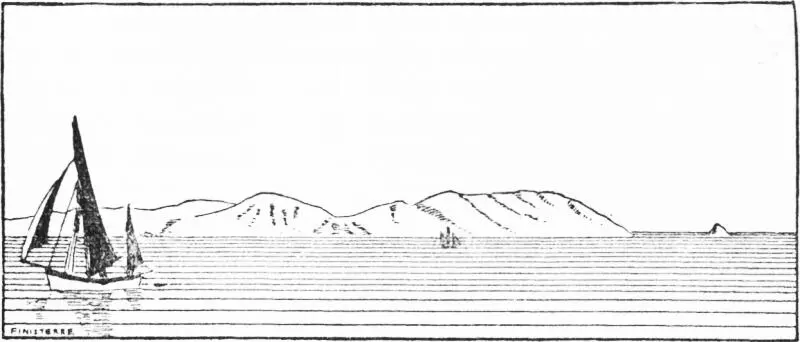

South of Finisterre they found the good weather again. They sailed right down the coast, outside the Burlings and the Farilhoes, those two groups of rocks on which so many vessels have been wrecked. They passed them at night, not seeing the wretched little green light of the Farilhoes until they had long been watching the brilliant gleam and flash of the Burlings, although the Burlings were much farther away. Then, the next morning, they took their departure from Cape Roca, outside Lisbon, and their coastwise sailing was over. Captain Flint set a course for Madeira, and, as Cape Roca dropped below the horizon, they knew they would see no other land until they sighted Porto Santo, nearly six hundred miles away.

Already those four days crossing the Bay of Biscay had accustomed them to being out of sight of land. Some people would have thought it dull, but there always seemed to be something to look at. It might be the gulls floating after the ship with hardly a flap of their broad wings, swooping down to pick up a scrap of biscuit that somebody had dropped overboard, or flashing close by the bulwarks and catching scraps flung to them in the air. It might be a steamship, a big liner from South America, or a long, low tanker, carrying oil, with its funnel right aft and no derricks, so that anybody could tell at once what it was. Or it might be a school of porpoises, plunging together through the crests of the waves, as if they were swimming a sort of water hurdle race. In and out, their backs gleaming in the sunshine as they turned over and down again, the porpoises raced together, and everybody used to rush to the side to watch them until their white splashes were too far away to be seen. Or it might be flying-fish, glittering silver things shooting out of the side of a wave, their long fins whirring, looking like little bright white flying pheasants, diving into the top of another wave, coming straight through it and out at the other side, and sometimes skimming the water for a long distance before they disappeared in it again.

There was always something to see. And, besides, there was always something to do. Susan and Peggy were busy from morning to night with their cooking and housekeeping. “Shipkeeping, it ought to be called,” as Roger pointed out one day when Susan said she was too busy housekeeping to knit a stocking cap for Gibber. Gibber, by the way, got his stocking cap all right, but it was knitted by Peter Duck when he had finished darning his socks. He knitted it from blue wool, on the pattern of his own, and Susan, when she saw it, let shipkeeping go hang while she made a red woollen tassel to go on the top of it.

Every day the main water tank had to be filled up from the small screw-top tanks that were stored under the flooring down below. In this way Susan was able to keep count of exactly how much water they were using. She never had been very good at sums, and neither had Peggy, but long before the end of that voyage nobody could have found fault with their additions and subtractions and divisions. They were calculating all the time, and often Susan would wake up in the early morning thinking that one of the sums had gone wrong, and then she would sit up in her bunk and work it out again, and tell Titty about it, and Titty, in the bunk below, would also have a go with pencil and paper, trying to help. Inside the deckhouse door there was a card, and every time one of those tins from down below was emptied into the main tank, Susan used to tick it off on this card, so that Captain Flint, too, was able to keep an eye on the way the water was going. They were very careful about the water, doing most of their washing in salt water, using special salt-water soap. It did not make much of a lather, and it left them feeling rather sticky, but anything was better than running short of drinking water. And in the end, Captain Flint said that it was all due to Susan that things went off so well. If she had not been so careful with the water they could never have done what they did.

They kept watches, too. And in fine weather John, Nancy, and Bill, two at a time, or sometimes all three together, had charge of the ship for four hours in the afternoon. They had a compass course to steer. There was no land for them to run into. And anyhow, in case of meeting other ships, or in case the wind played any tricks, they could always bang on the deckhouse door and bring out Peter Duck or Captain Flint, who tried to get some rest during the day, because at night one or other of them was always on deck. Bill, of course, had been steering small sailing vessels ever since he could remember, and John and Nancy had learnt a lot about it by the time they had come so far. And, of course, all day, no matter what was going on in the way of shipkeeping, it was the duty of everybody who happened to be on deck to keep a good look out.

SUMS

SUMS

Peter Duck taught them how to make nets, and, taking turns at it themselves, and with a bit of help from him, they made a hammock and slung it between the foremast and the windward shrouds, and collected a good lot of bumps between them, what with trying to get into it or out of it while the Wild Cat went carelessly swinging along, up and down, over the ocean waves. The hammock was a great success, but nobody wanted to stay in it very long. Staying in it meant keeping still, more or less, if you did not want to roll out. They tried playing deck-quoits over the top of it, throwing rope rings (which Peter Duck showed them how to make) to and fro, catching them and throwing them back again. But so many of the rope rings went over the side that they grew tired of making new ones, and Peter Duck said there would be a shortage of spare rope if they went on with that game too long.

Then they took to skipping. Everybody thought this would be rather a childish game when Captain Flint first suggested it, but they very soon found they could collect bumps even better with the skipping-rope than with the hammock. It was no joke at all, skipping on the sloping deck of a little schooner, especially as the slope of the deck was never the same for more than a second or two at a time. Even Bill saw that there must be something in it when he had watched Captain Flint skipping most solemnly, a hundred skips with the right foot first, a hundred with the left, and then fifty with both together, when he sank exhausted on the skylight. Bill tried. He did not sink exhausted on the deck, because he had not time. The deck came up and met him very hard before he had got through his first three skips. In the end they all got pretty good at skipping, and it came a lot cheaper in rope than the deck-tennis over the top of the hammock.

Читать дальше

SUMS

SUMS