“As for where we’re bound for,” Captain Flint went on when the mug seemed to be empty. “We don’t yet know ourselves. Now then, my lad, you skip along, get into some dry clothes, and tell that skipper of yours that if there’s anything else he wants to know, he’d better come and ask. Got another slice of cake there, Susan? And give him his hooks and line, Titty.”

The red-haired boy grinned for the first time.

“Thank you, sir,” he said.

“Skip along,” said Captain Flint. “You know as much as we do now. And you could have learnt it all without going swimming.”

“And take a word from me, young Bill,” said Peter Duck. “You’ll come to no good shipping with Black Jake.”

The boy looked round the little group. “I must go to sea, somehow,” he said. “And if the others won’t take me . . .”

“Well, skip along,” said Captain Flint. “We’re busy. Sailing in the morning.”

And with that the boy, munching one hunk of black juicy cake and carrying another, given him by Peggy, for future use, climbed up the ladder to the quay and went slowly off towards the bridge, on his way round to the other side of the harbour and the black schooner that lay there without a sign of anybody being aboard her.

“As for where we’re bound, we don’t know ourselves,” and “Three captains aboard and two mates. . . .” If Captain Flint had been trying to find the very words that would make Black Jake more curious than ever, he could not have chosen better.

“I’d think twice about jumping in like that just for the sake of asking a question,” said Captain Flint when the red-haired boy had gone.

“But he was pushed in,” said Titty. “I’m sure he was.”

“Oh, rubbish,” said Captain Flint, but a minute or two later he spoke to Peter Duck. “Who does that boy belong to?” he asked.

“He don’t belong to anybody, properly speaking,” said Peter Duck. “He was born in a trawler. His mother died when he was a baby. His dad was lost in a gale a year or two back and young Bill looks after himself mostly. There’s hardly a vessel out of Lowestoft that hasn’t found him stowing away to get to sea.”

“H’m,” said Captain Flint, and glanced across the harbour. “I wonder if we ought to have let him go back.”

But there were many other things to think of in the Wild Cat that night. Swallow had to be brought inboard again and lashed down under a canvas cover. Many a long day was to pass before she would be afloat again. After all that day’s work on the rigging, there was a lot of rubbish, scraps of rope and wire, to be cleared off the decks. Then there were one or two more last-minute purchases to be made. John, Susan, Nancy, and Peggy went off into town to make them. Captain Flint took Titty and Roger with him to the harbourmaster’s office. He wanted to make sure that the Wild Cat should not lose her berth by going out for a trial trip. He wanted to be able to come back to the same place after the trial trip. Roger took his chance and told the harbourmaster the story of Bill’s tumbling overboard and the rescue. Titty once more said she thought Bill had been pushed in. The harbourmaster laughed. “Well,” he said, “I wouldn’t let a boy of mine ship with that fellow. He’s in with every bad lot about the place. Not that I think he’d push a boy into the harbour There’s no sense in that, no sense that I can see.”

By the time they got back, supper was ready, and soon after that, knowing that they were to start with the morning tide Captain Flint hurried his crew to bed.

Table of Contents

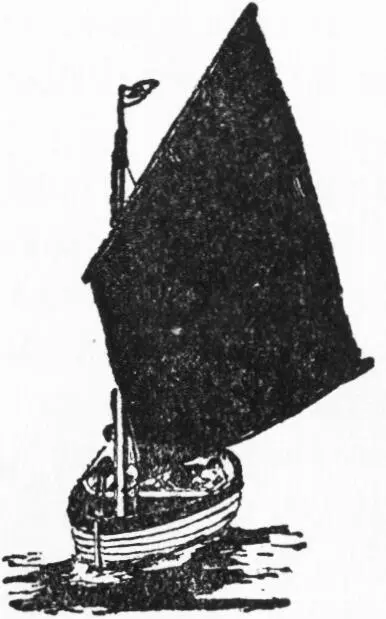

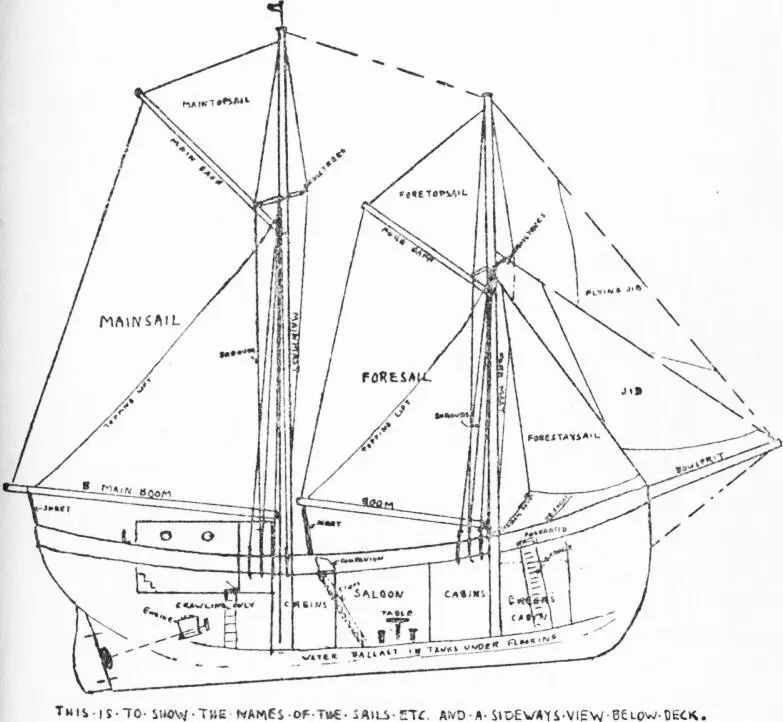

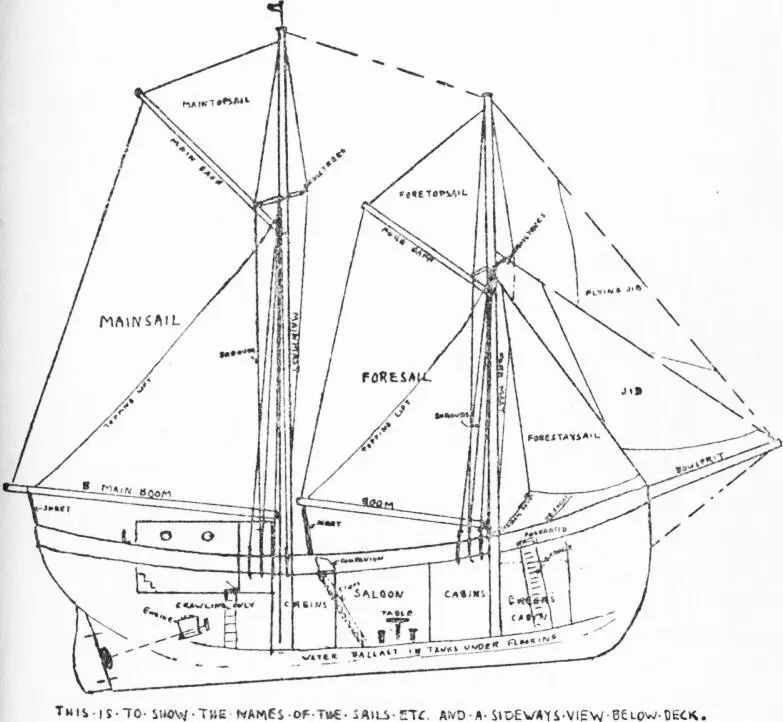

Not one of the crew had thought sleep at all possible that night and all of them were surprised when they heard a bumping on the deck above their cabins, and woke up to find that it was already daylight. They had forgotten to put out the hanging lantern in the saloon and it swung there looking like a ghost. There was very little washing done below decks before Susan hurried up the companion and found that someone had already been ashore and brought a milk-can full of fresh milk, and also that someone had lit the oil-stove for her in the galley. The kettle was close on boiling. The others, after a lick and a scrub, came hurrying on deck, some by the companion, some up the ladder through the forehatch. They found that it was not only in the housekeeping line that a good deal had been done that morning. The Wild Cat somehow looked altogether different. The topping lifts had been set up and the booms lifted. Mainsail and foresail, lovely new creamy canvas, were cast loose ready for hoisting. The staysail was at the foot of the forestay, held in a bunch with a bit of thin twine that would break at the first pull on the halyards. The jib had been hoisted already, but in stops, rolled up, that is, and tied, so that a pull on the jib sheets would be enough to break it out.

“This looks like business,” said Nancy.

“I should just think it does,” said John.

The other vessels in the harbour were all asleep. There was still dew on the rail and on the top of the deckhouse. But, early as it was, someone was already awake about the quays, for the pier head lights had vanished, and the thin morning sunlight was falling on a red flag hoisted on the flagstaff by the swing bridge to show anybody who might want to know that there was a depth of ten feet at least between the heads. Everybody looked across to the Viper, but the black schooner lay there beside the opposite quay without a sign that anybody was aboard her.

Breakfast was almost as much of a scramble as washing. They had it on deck—just thick bread and butter and steaming mugs of cocoa. As soon as that was done, indeed, while some people were still eating their bread and butter, they crowded into the deckhouse to look at the chart already spread out on the table. Everybody leant over it while Captain Flint pointed out the way they were going.

“The wind’s almost due east just now,” he said. “We’ll use that to throw her head off, but we won’t try going out under sail, not the first time with a new crew. We’d have to tack out against the wind and I’d like to be sure you all of you know your ropes before we start that sort of thing. No thanks, Susan. I’ve had enough, for now anyway. All hands on deck, and let’s see what sort of a job we make of getting up the mainsail. We’ll have it up now, though we’re going out with the engine. All right, Roger, we’ll be going down to look at it in a minute.” Roger was already lifting the trap-door in the floor of the deckhouse where there was a short ladder down to the stuffy little engine-room.

“Throw her head off?” said John.

“Hoist the staysail and hold him to wind’ard to force her head off the quay,” said Peter Duck.

THE WILD CAT

THE WILD CAT

Everybody hurried out on deck.

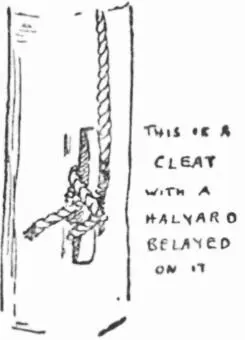

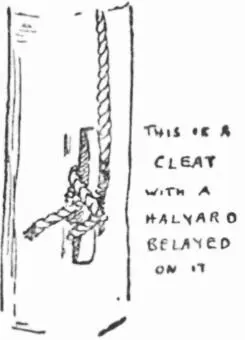

“Now,” said Captain Flint. “Mr. Duck and I can hoist that mainsail between us. But we have to take one halyard at a time, and belay the peak1 while we’re hauling on the throat. Let’s see what we can do with the lot of you tallying on. Come on, then. Nancy and Peggy haul away on the peak with me. John, Susan, and Titty haul away on the throat with Mr. Duck. All right, Roger. Room for you here. Titty’s chantyman. Pipe up, Able-seaman. Let’s have ‘A Long Time Ago.’ Mind everybody hauls together at the right words.”

Читать дальше

THE WILD CAT

THE WILD CAT