– God makes a distinction within Israel—and presumably within the world of the nations as well—between the group of the wicked and that of the Yhwh-fearers. There can be no reconciliation between these two groups; the wicked will be utterly eliminated (Mal 3:13–21 [3:13–4:3 ET]).

– The Malachi document presupposes that blessing comes from an intact covenantal relationship. The covenant is established by Yhwh as a one-sided act of graciousness, but the human partner is also obligated to bring God gifts in response (מנחה, minḥāh in Mal 1:10, 11, 13; 2:12, 13; 3:3, 4). If these are neglected or treated carelessly, the blessing ebbs and is replaced by cursing. Nature, which seems to be included in the covenant, also then refuses to cooperate with humans and brings no further yield. Rather, it grows barren (Mal 3:10–12).

– The effects of blessing wrought by the covenant include harmony and solidarity within Israel. The idea is that God binds people together in fidelity. If that fidelity is ruptured, that touches God as well. The Malachi document mentions two groups to whom injustice is being done: the “wife of your youth” (Mal 2:14, 15), and the personae miserae (Mal 3:5).

– The Malachi document allows opponents to speak. These assert that people who have done their duty before God have received no corresponding recognition (Mal 3:14). Astonishingly, the prophet agrees with these opponents and even calls upon them to test whether they will receive a reward for their obedience (Mal 3:10).

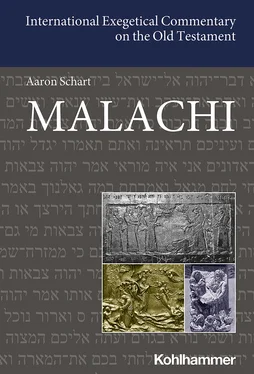

Malachi 1:1

Superscription

Translation

1 A weighty speech a. The word of Yhwh to Israel by Malachi.

Notes on Text and Translation

1a In the context of the superscription the word משׂא, maśśā’ , literally “heavy load,” must have a technical meaning and refer to a prophetic genre. The translation “weighty speech” seeks to combine the underlying meaning with its prophetic application. Syntactically it is most probable—contrary to the Masorete’s reading and that of the LXX—that we are dealing with two superscriptions set alongside one another. 1In terms of today’s publishing norms we may compare this to the combination of a title and a subtitle. The first superscription consists only of the term “weighty speech.” The second offers a prepositional addition in which the underlying expression “word of Yhwh” is clarified by the addition of two prepositional phrases.

The LXX did not understand the consonantal text מלאכי as a personal name; otherwise it would have transcribed the Hebrew word, as was usually the case with proper names. Instead it read the word as an honorary title: “my messenger.” It also changed the first-person suffix “my” to the third person “his” because the superscription is not spoken by God but comes from the editor of the document. The expression “Yhwh’s messenger” is also used as a title for Haggai (Hag 1:13), so it was natural for the translator of the Dodekapropheton to read it as a title in Mal 1:1 as well. The LXX adds a challenge to the superscription: “Therefore take (it) to heart!”, which is drawn word for word from the Greek text of LXX Hag 2:15, 18 (twice). It is also referred to in Mal 2:2. The Septuagint thus understands the Malachi document as a continuation of Haggai’s message.

The Malachi document, like most of the books in the Book of the Twelve, begins with a superscription. Malachi 1:1 is of the usual type, a simple sequence of nominal clauses.

On the one hand the superscription presents a clearly-marked new beginning while presupposing the text of the preceding documents. On the other hand, by using the same generic title, “weighty word,” found also in Zech 9:1 and 12:1, it also establishes continuity with the Deutero-Zechariah chapters Zechariah 9–14. Yet, since only Mal 1:1 contains a personal name, only the Malachi document is regarded as an independent prophetic writing, while in contrast the textual units Zechariah 9–11 and 12–14 are considered integral parts of the Zechariah document.

The superscription consists of two independent generic designations set alongside one another. The first is משׂא, “weighty word,” and the second is דבר־יהוה, “word of Yhwh.” This latter expression is expanded by the naming of the addressee (“to Israel”) and the mediator (“Malachi”). Each of these elements is in itself a generic concept within the framework of prophetic superscriptions. 2Their combination as a clustered superscription is unique, but it seems that the two are not intended to be mutually exclusive; rather, they augment one another. Still, the impression of some kind of tension remains.

“Weighty speech” The generic concept of משׂא signals a prophetic claim; in any case it is found only in prophetic books. The concept “word of Yhwh” is the more comprehensive, משׂא the narrower. The word משׂא is derived from the root נשׂא, “to bear,” and properly means “burden” (cf., e.g., Jer 17:12–11). As a rule the burdens are so heavy that they have to be borne by animals, and they can be too severe even for them (e.g., Exod 23:5). But in the superscriptions the word must have a special, technical meaning and represent a genre.

– Judging from the etymology, this technical meaning must reflect something that represents a severe “burden” for the addressees. 3We may well suppose that the prophet had in mind something weighty, pressing down on those he addressed, something under which they would suffer, and he sought to express it in a single word.

– A consideration of the rhetorical units under this heading reveals a striking number of sayings directed against foreign nations (e.g., Isa 13:1; 15:1; 17:1; 19:1; 21:1). The conspicuous resemblance to the usage of משׂא in Zech 9:1 and 12:1 supports the idea that Mal 1:1 should be directly linked to Zech 9:1 and 12:1. While the theme of foreign nations is prominent in Zechariah 9–14, that is only marginally the case in the Malachi document, as when in Mal 1:4–5 the downfall of the people of “Edom” is announced.

“Word of Yhwh” The generic term “Word of Yhwh” indicates a claim that in the writing to follow Yhwh is speaking. In Israelite understanding the word of Yhwh was conveyed through individuals who could “hear” the divine voice directly and intuitively. This idea likewise implied that these persons had access to Yhwh unavailable to others. Such a claim to exclusive access to the divine voice was notoriously difficult to prove to hearers, but when the corresponding speech was recorded in writing and given a prophetic title the act demonstrated at least that there was a community that acknowledged the claim of access to the divine voice and attested to that by its personal responsibility for passing on these words to later generations.

“Israel” Another element frequently encountered in prophetic superscriptions is the naming of the addressees, who are to be presumed everywhere in the body of the text where no others are explicitly named. “Israel” is, in principle, understood to be the people of God even though it is appropriate in different contexts to question exactly what the author understands the people of God to be. 4In the Malachi document the name “Israel” is only used in secondary additions (Mal 1:5; 2:11; 2:16). 5We may therefore suppose that the naming of Israel in the superscription either presupposes these additions that mention Israel or that those additions have a literary-historical connection to the superscription.

The name “Malachi” Authorial names are characteristic elements of the superscriptions of prophetic books, so in Mal 1:1 מלאכי must be a personal name, even though the LXX understands “ malaki ” as an office and the name lacks any further descriptive notes usually added to identify the person, e.g., a patronymic or place of origin (Hos 1:1; Joel 1:1; Amos 1:1; Mic 1:1; Zeph 1:1). 6

Читать дальше