Whilst I was writing this book I was working in the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera), teaching in the Faculty of Anthropology of the European University of St Petersburg and producing the Anthropological Forum journal. I am very grateful to my colleagues in the Kunstkamera, the Faculty and the journal’s editorial board for the unfailing support I experienced throughout the whole period.

Finally, the author and the translator would like to give special thanks to Professor Catriona Kelly for her invaluable assistance.

Albert Baiburin

November 2020

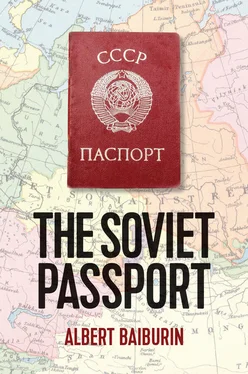

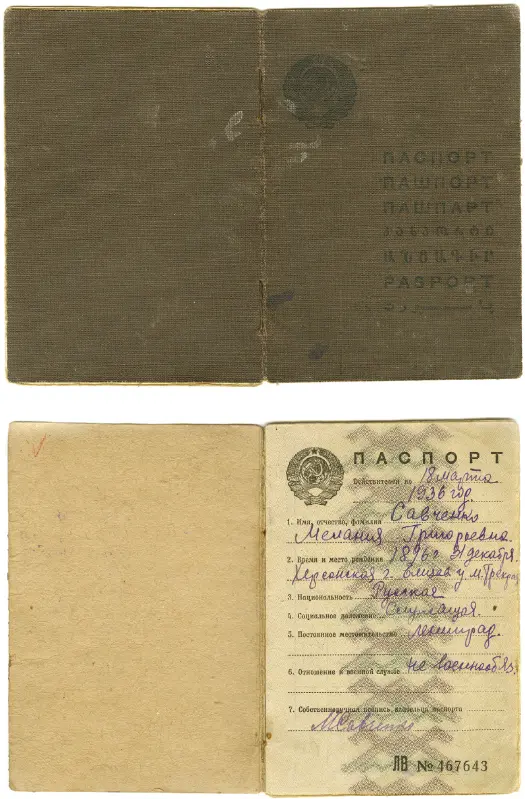

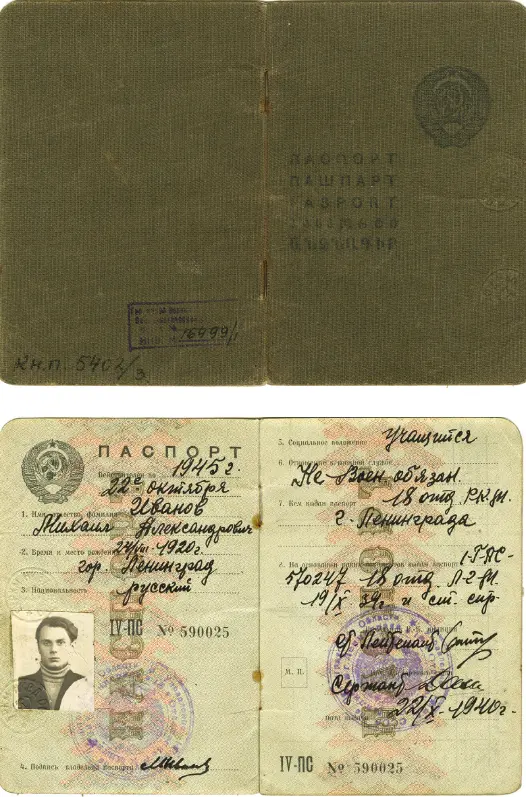

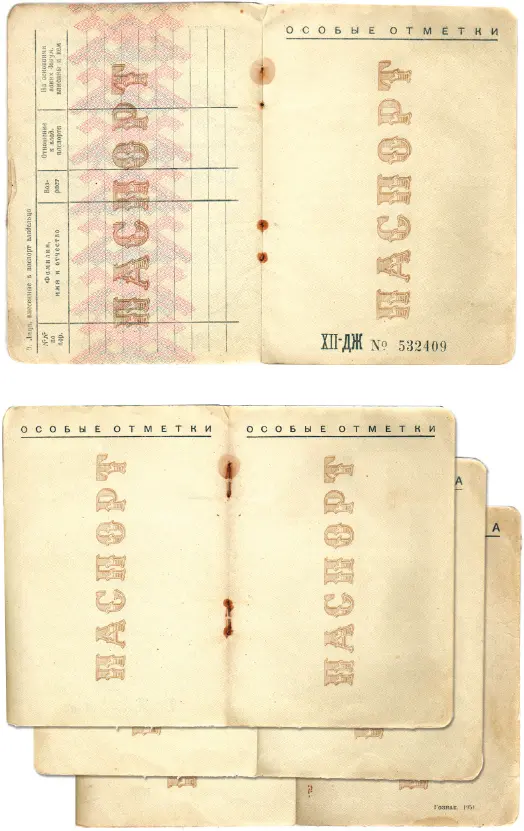

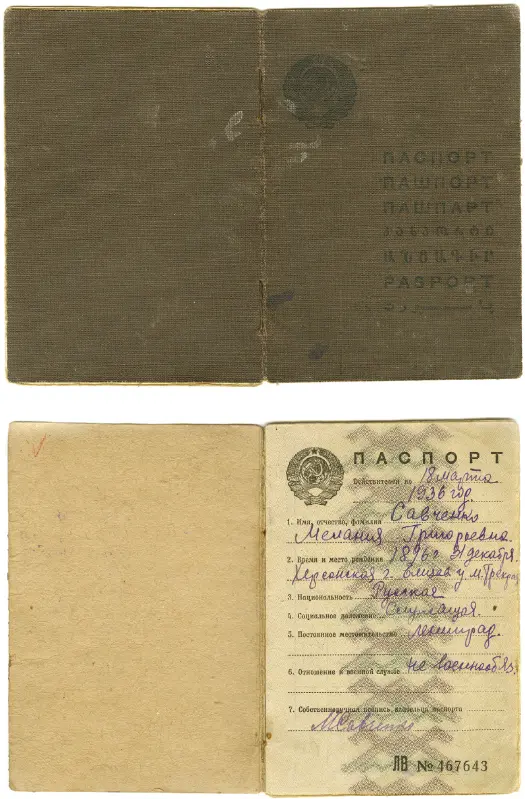

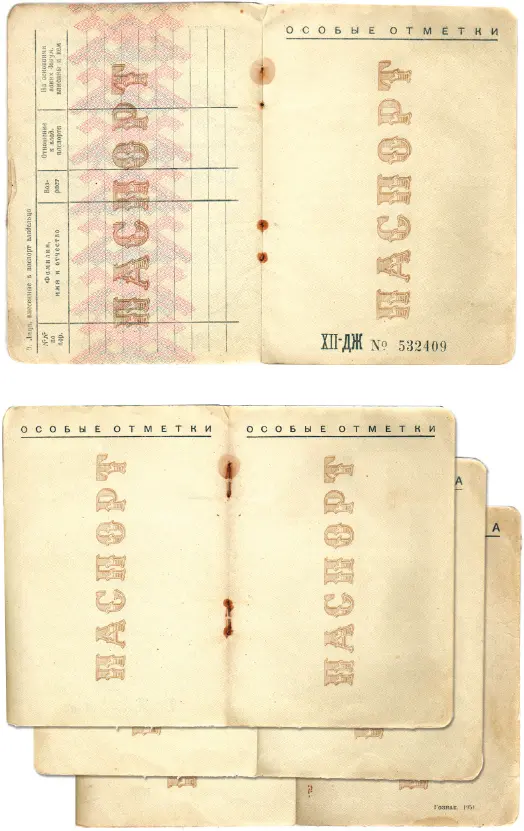

Plate 1(a–d):The 1933 passport.

(Source: State Museum of Political History.)

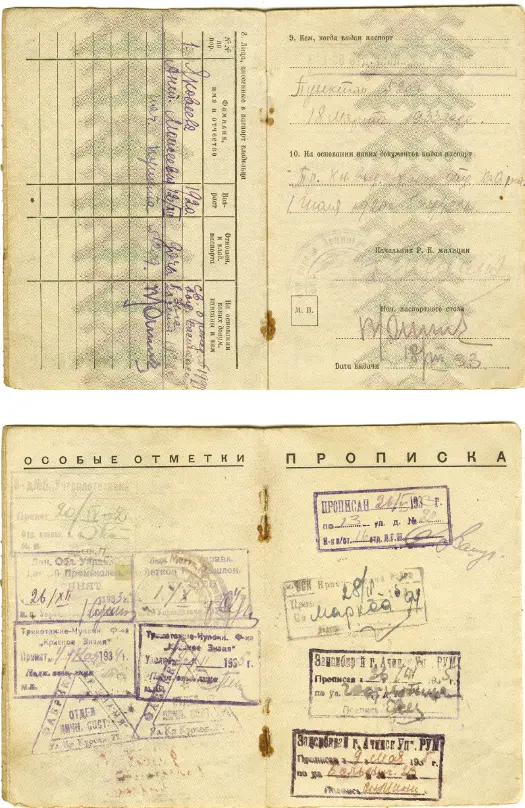

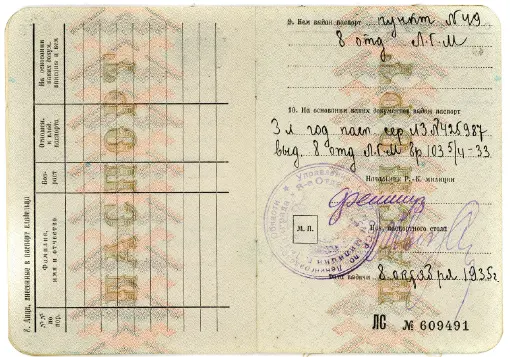

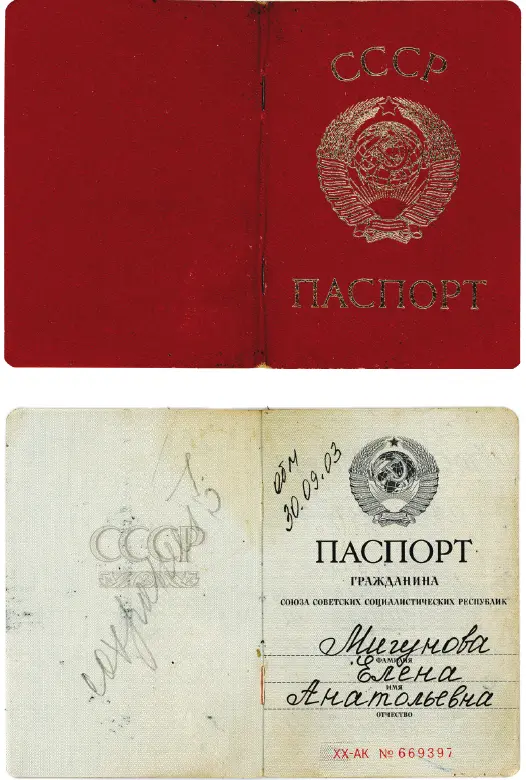

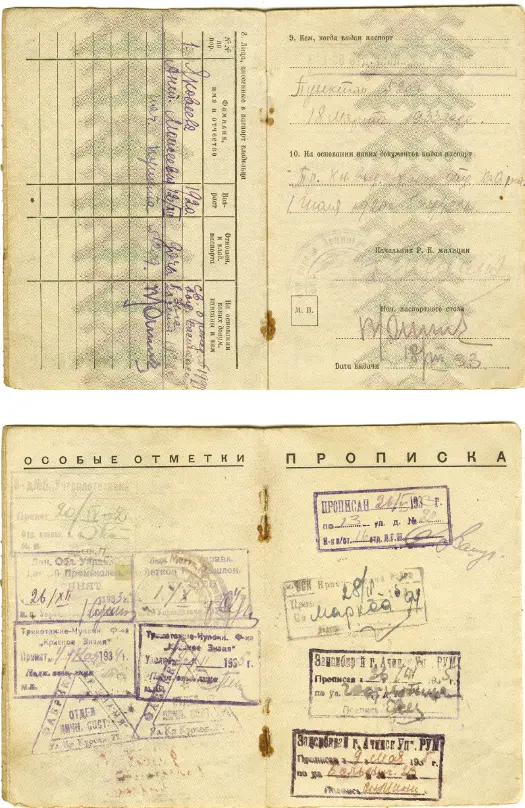

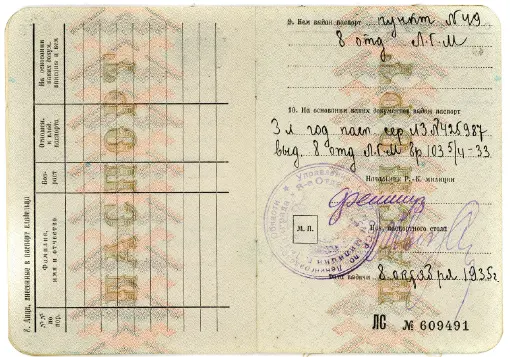

Plate 2(a–c):The 1935 passport.

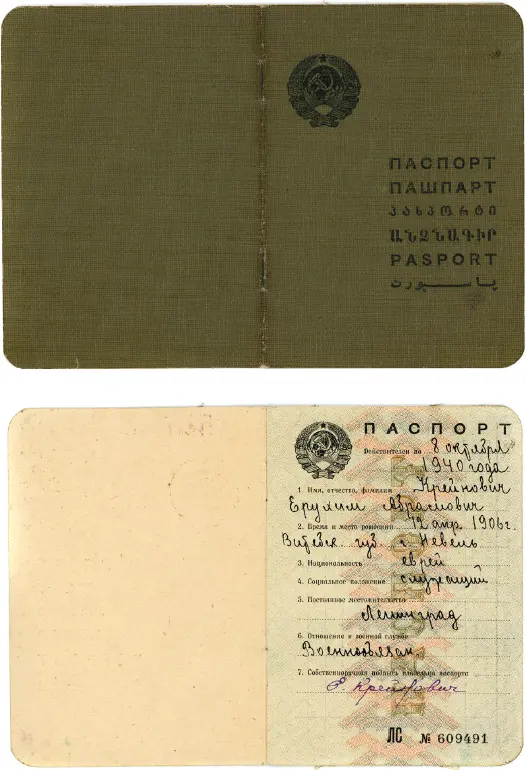

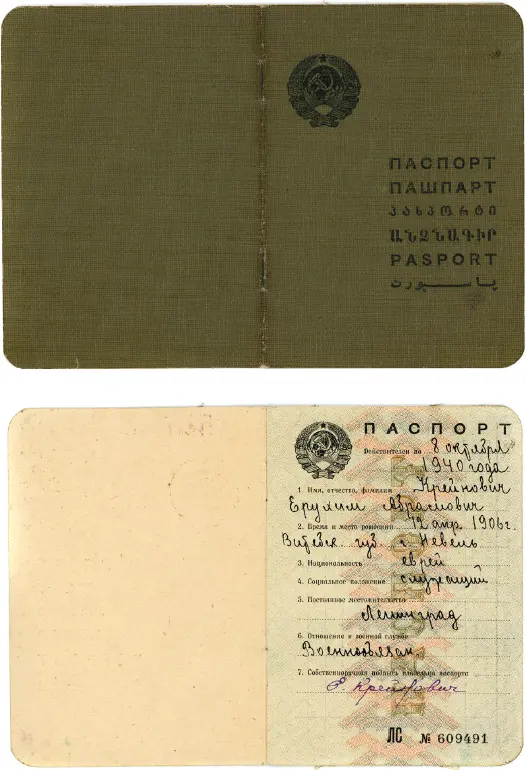

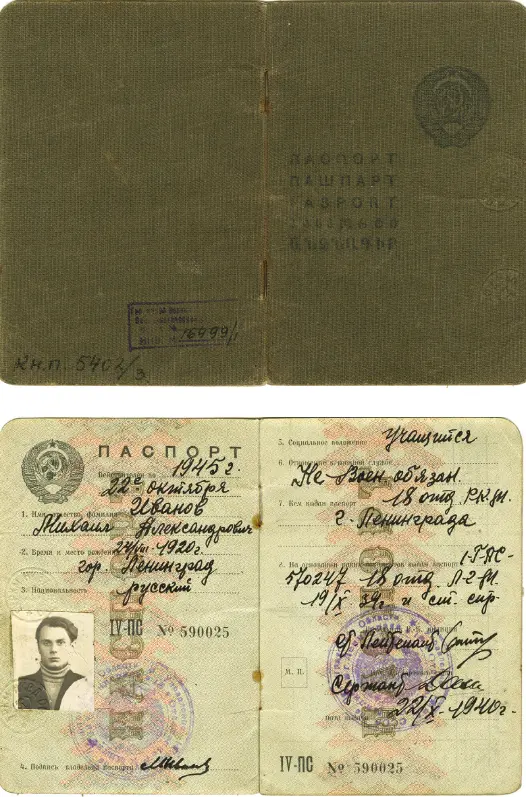

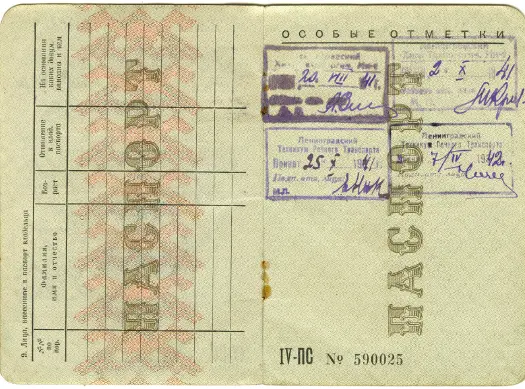

Plate 3(a–c):The 1938 passport.

(Source: State Museum of Political History.)

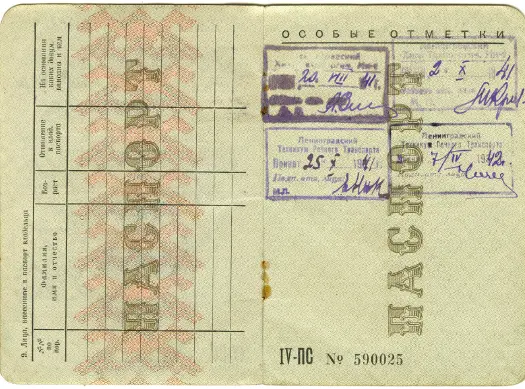

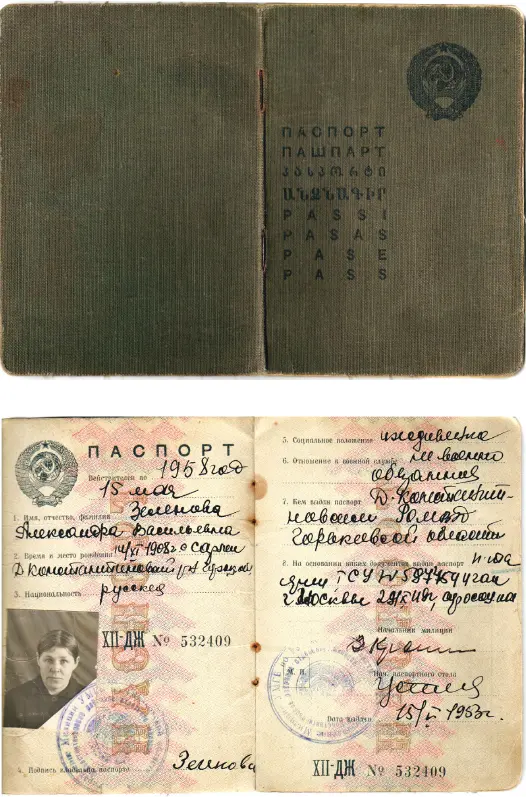

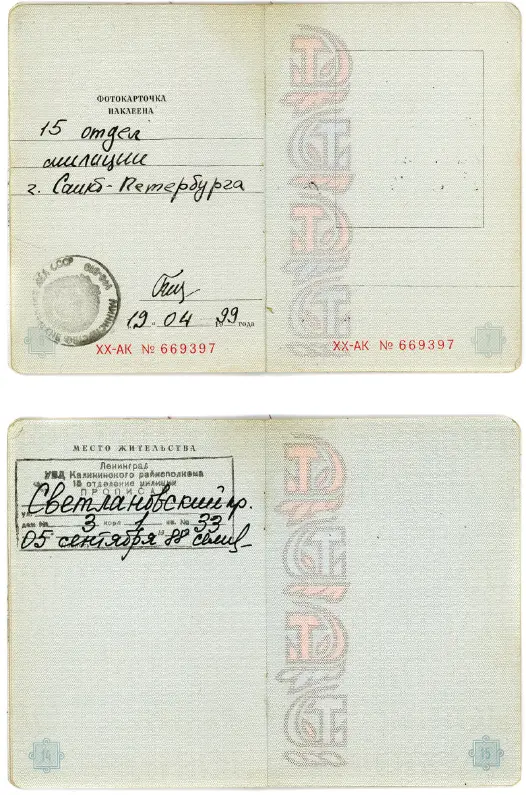

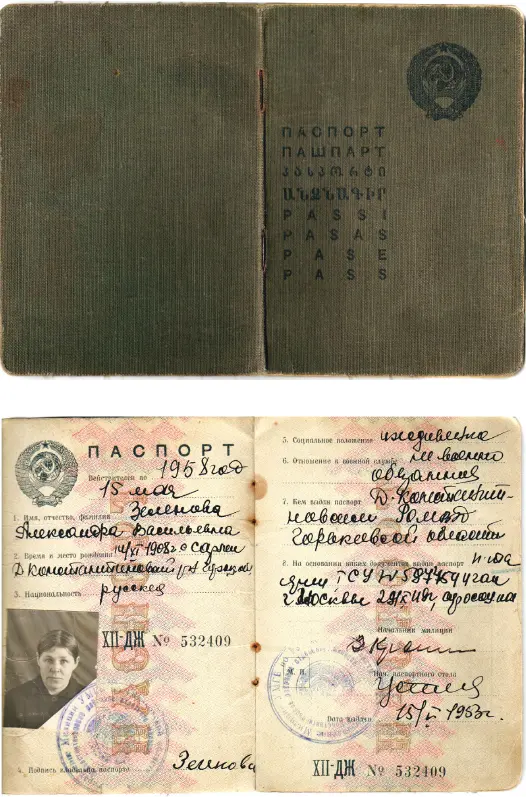

Plate 4(a–d):The 1951 passport.

(Source: archive of Krasheninnikov family.)

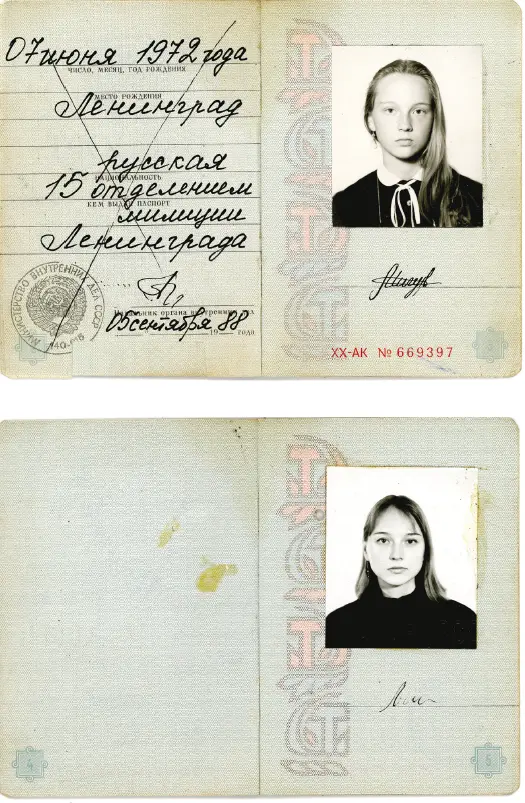

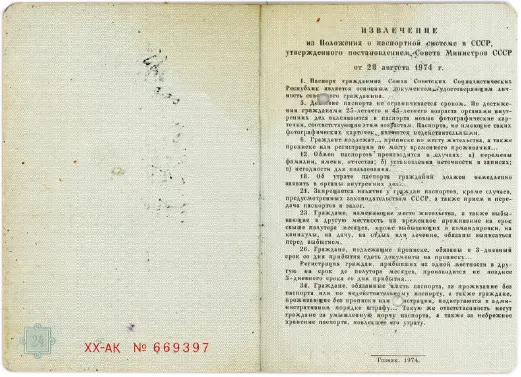

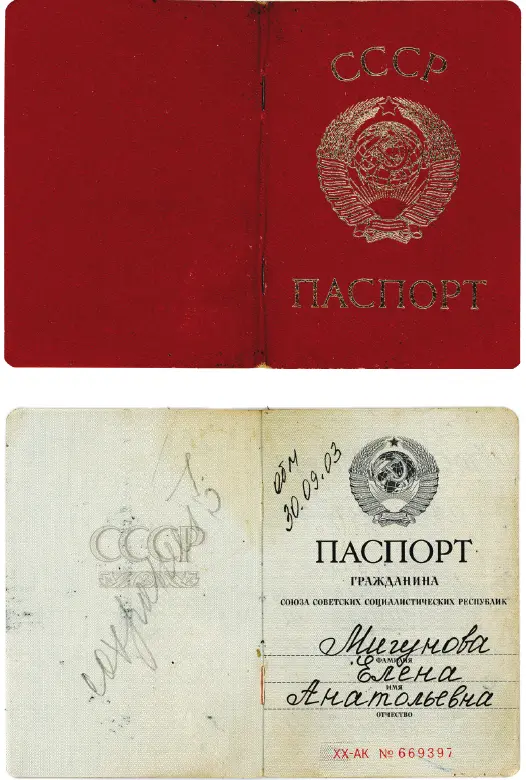

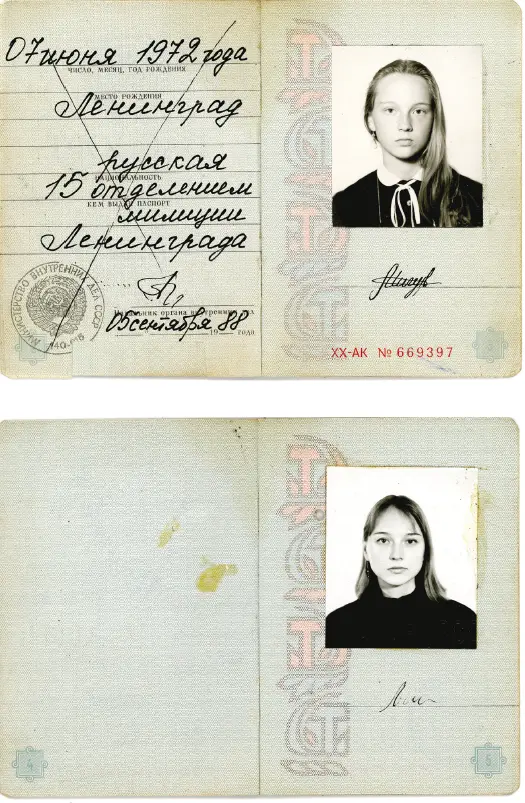

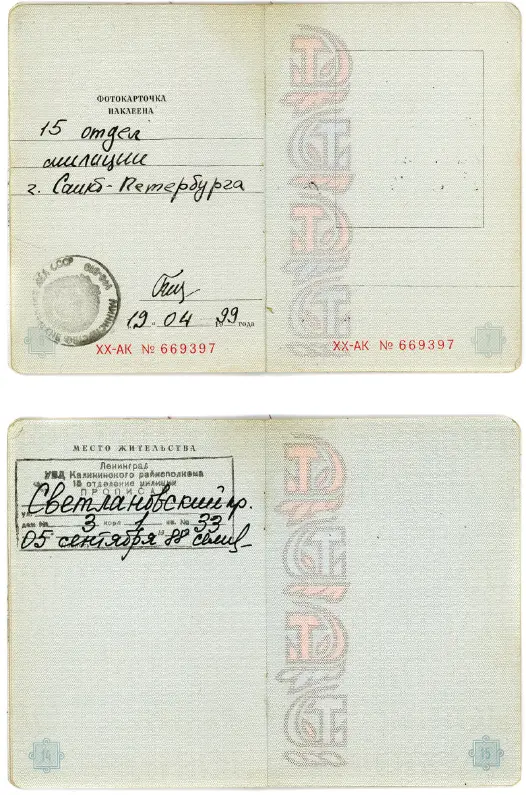

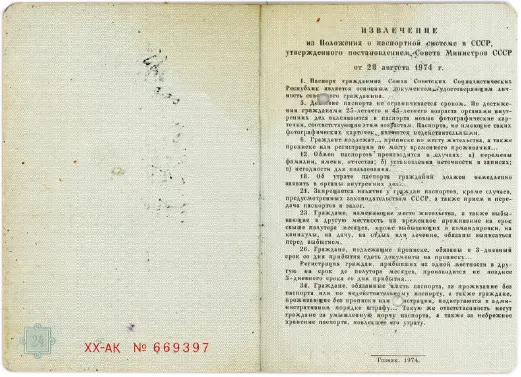

Plate 5(a–g):The 1974 passport.

(Source: archive of the Levichkin Family.)

Remove the document – and you remove the man.

Mikhail Bulgakov 1

The above quotation from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel, The Master and Margarita , highlights a rarely acknowledged fact: in our modern civilization a person exists only as long as they can be pinned down and represented by a variety of documents. This may be an exaggeration, but it is not a great one. This is exactly the rule which applies when someone is dealing with officialdom. This book focuses, on the one hand, on the individual’s details which are laid out in the passport and their ‘invention’ by the bureaucratic apparatus, and, on the other, how specific people have gained mastery over them. This approach involves examining the creation of the passport system and the development of the image of the passport in the wider context of pre-revolutionary and Soviet social history.

Once the passport system had been introduced, we could say that the Soviet people had been given ‘instructions for identification’. The understanding of the word ‘instructions’ in the Soviet (and, indeed, post-Soviet) tradition has a very direct meaning: it is a particular order – usually written – or a demand from the authorities (such as an instruction to appear at the military call-up office, or an instruction to improve your behaviour). The Soviet passport, which was introduced in 1932, implicitly contained the demand that the individual identify him- or herself according to the descriptions laid down within it. This referred not only to those citizens who received the passport, but also to those who were denied one. In reality, the whole adult population of the country was obliged to apply to themselves the definitions laid down in the passport, thus carrying out their own form of self-identification. In this sense it was not even the authorities who defined the ‘passport portrait’, but the actual passport itself became the means of identification.

The term ‘identity’ does not appear frequently in this book, because this carries with it the inherent sense of referring to something definite. In keeping with the work of Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, I prefer the term ‘identification’, which refers specifically to a process. 2As they point out, the very term ‘identification’ requires clarification as to who it is that needs to be identified. This is particularly important since the question here concerns the state’s system of the external identification of the individual. Through its particular institutions the state has developed a specially codified categorization system, which is laid out in the passport. This system of identification and categorization imposed from without cannot but have an effect on the self-identification of the individual. The cultural and social effects which such a clash of interests brings about are of particular interest to me.

The passport has traditionally been considered as one of the fundamental symbols of Soviet life. A vast myth grew up around the Soviet passport. Poets, writers, ordinary citizens and, of course, historians and other scholars all played their part in creating it. In this myth the passport becomes an object of special value, one that is inextricably linked with the understanding of what it is to be ‘a citizen of the USSR’. It is perhaps the most interesting document in the history and practice of relations between the person and the state. Originally created to identify the individual and to impose control over their movement (especially over crossing borders), it gradually took on a whole host of meanings, at times far removed from its original purpose. And it was not simply the bureaucrats who endowed the passport with these meanings, but also those to whom it was issued. This is probably more relevant for the Soviet passport than for any other. 3And many aspects have remained the same up to the present day.

Soviet citizens – and Russians now – have two passports. In Soviet legal practice permission to cross state borders was possible only with the so-called ‘foreign travel passport’. The ‘internal’ passport was a particular phenomenon. Its basic role was to certify a person’s identity, but it was used for far more than simply this. In a multiplicity of situations this passport had a far greater significance than did the actual ‘person’ whose identity it proved. There is a huge body of evidence which illustrates that without it a person literally ‘disappeared’ from the life of their society. It was impossible to find employment, or place your child in a kindergarten or a school; a person could not marry or ultimately die ‘correctly’; or even fulfil what seem such simple practices as obtaining a library ticket or picking up a parcel from the post office. It was absolutely essential on virtually every occasion when there was contact with officialdom (including obtaining any other documents), because it was always necessary to prove that the citizen was the person whom they claimed to be. And in the Soviet system of social relations, a person could prove who they were only with the aid of the passport. 4

Читать дальше