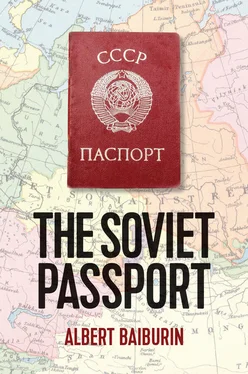

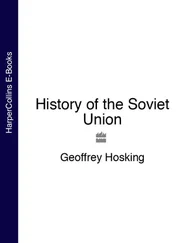

Figure 3 :Employment List, issued to Dina Isayevna Zakharina.

(Source: author’s personal archive.)

Apparently, the authorities were not ready to take decisive action to bring order to the system of documentation, especially as a year earlier (by the Law of 24 January 1922) all citizens of the Russian Federation were given the right of unrestricted travel across the whole territory of the RSFSR. This right was enshrined in Article 5 of the Civil Code of the RSFSR. 27Nonetheless, a decree was prepared on the introduction of a single identity document for the whole country (known as the RSFSR VTsIK and SNK Decree of 20 July 1923). The previous decree on the introduction of employment books in Moscow and Petrograd was annulled. The new decree opened with an unusual article:

Government bodies are forbidden to demand that citizens of the RSFSR produce passports or other residence permits which might hinder their right to move or settle within the RSFSR. Note: Passports and other residence permits for Russian citizens within the RSFSR, as well as employment books, which were introduced by the decree of 25 June 1919 of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee and the Soviet of People’s Commissars are annulled from 1 January 1924. 28

In case of necessity, citizens could still receive an identity document, but this had become their right, not their obligation. In order to obtain the certificate, a citizen had to produce one out of a number of possible documents: in cities and smaller towns this could be a stamped or just an old birth certificate, house-management certificate, or proof of residence, work or service; in rural areas it was sufficient to show a birth certificate or certificate from the local soviet proving residence. If it were not possible to produce any documentation, the militia would give out a certificate which was valid for enough time for a replacement document to be issued. Article 21 stated that this should be no longer than three months, but in certain circumstances this could be extended by a further three months. Should all documents have been lost and if it were impossible to obtain a copy, an identity document could be issued on the strength of a court resolution, confirming surname, name, patronymic, date of birth and family status. 29

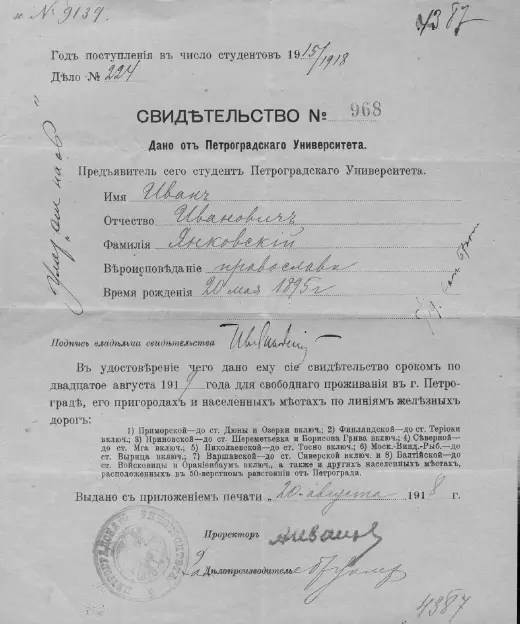

The identity document was issued either with no end date or for three years, and contained the following details: surname, name, patronymic of the holder; date of birth; place of permanent residence; occupation (main employment); liability for compulsory military service; marital status; and list of children under the age of sixteen who appeared in the parents’ documents. If the recipient so wished, their photograph could be inserted.

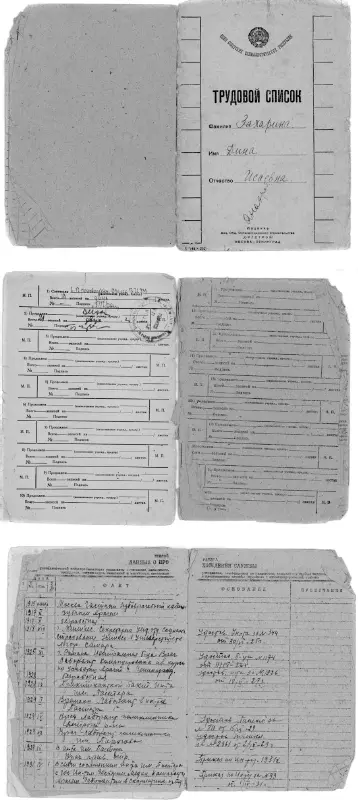

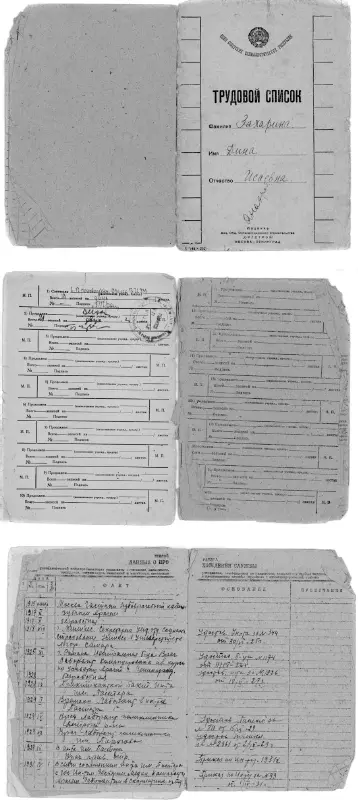

Figure 4 :Student’s Certificate from 1918, issued to Ivan Ivanovich Yankovsky by Petrograd University.

(Source: State Museum of Political History.)

It is not difficult to see that the details in the certificate reflected almost exactly the same ones as were in the pre-revolutionary passport. All that is missing is ‘rank or title’ (social standing); but this is simply because these identity documents were issued only to ‘workers’. ‘Non-working elements’ were put into a particular category labelled ‘the disenfranchised’ [Russ: lishentsy ]: people who had no political or civil rights. The ‘non-working elements’ included former landowners and merchants; NEPmen; 30petty traders; former police officers, security guards or prison warders; and also former members of the clergy. They were registered on a special list until 1932, and it was only in the Constitution of 1936 that they were recognized as having equal rights.

The lack of an identity document did not lead to any legal consequences. What was more, because it was not compulsory to have such a document, its value as a document confirming identity was questionable, if only because it did not usually contain a photograph of the holder, nor the kind of written ‘portrait’ that was found in pre-revolutionary passports. 31

Thus began a short period when citizens were effectively freed from the necessity to own a passport and they were not tied down to a particular place of residence. Such a situation was suitable for the ideas of the New Economic Policy and helped create the freedom essential for the development of market relations. A passport was needed only if a citizen were travelling abroad. The situation could not even be obstructed by the Resolution of the SNK RSFSR which was published two years later, on 27 April 1925, with the frightening title, ‘On the Registration [Russ: propiska ] of Citizens to Live in Urban Settlements’. 32In line with this Resolution, the propiska could be issued on the basis of almost any document (from a trade union card to an employment book), which made it a mere formality. This did not exactly mean that the authorities could not use it to force a person to live in a particular place, but it made doing so very difficult.

Only now was it possible to say that the former passport system was dead. What Lenin had written about in 1903 had been achieved. The passport – which Lenin had described as ‘an outrage against the people’ – had become a thing of the past. 33This was how Nikolai Vladimirovich Timofeyev-Resovsky summarized this period in his memoirs:

There was a time in the 1920s, it seems to have been Lenin’s influence [Lenin died in January 1924 – Tr.] … when we began to establish normal relations with other countries. A Soviet citizen could buy a passport for foreign travel for thirty-five roubles and travel and even receive healthcare wherever they wanted. From the winter of 1922–3 until the winter of 1928–9 we had virtually free access to foreign travel … Within the country, the employment book fulfilled the legal role of the internal passport. But for a few years, effectively the period of a five-year plan, we had freedom, more or less. 34

Yet only a short time would pass and the passport system would go from being ‘an outrage against the people’ to an essential ‘order of administrative registration, control and regulation of the movement of the population by means of the introduction of the latest passports’. 35

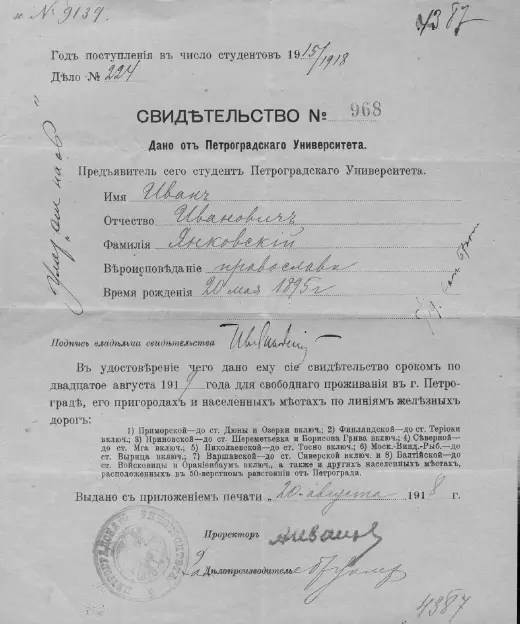

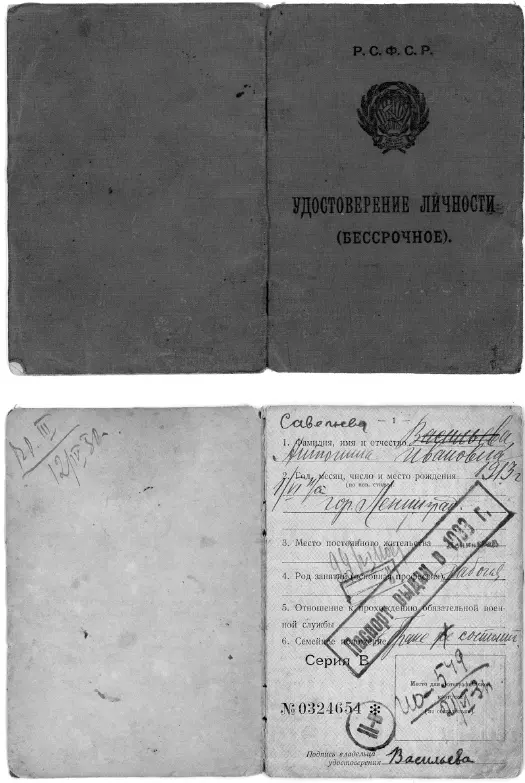

Figure 5 :Identity document with no end date, issued to Antonina Ivanovna Savelyeva. 36A stamp has been added at a later date stating that a passport was issued to the holder in 1933.

1 1. Vladimir Lenin, ‘To the Rural Poor’, from Lenin Collected Works, Vol. 6, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1964. This quotation accessed via https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1903/rp/5.htm#v06zz99h-398, 5 April 2020.

2 2. [According to the Julian Calendar by which Russia was still operating. This was 24 November by the Gregorian Calendar, to which Russia switched on 14 February 1918. – Tr.]

3 3. https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/events/revolution/documents/1917/11/10.htm, accessed 5 April 2020.

4 4. Albert Baiburin, ‘Iz predystorii sovietskogo pasporta…’.

5 5. Sobraniye Uzakonenii raboche-krest’yanskogo pravitel’stva…, p. 78. The resolution itself, called ‘The need for visas in passports for entry into Russia’, was signed on 2 December 1917 by Leon Trotsky.

Читать дальше