Having effectively declared the internal passport system no longer valid, the new authorities set about erecting barriers between Soviet Russia and the outside world. As early as 2 December 1917, the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs (NKID) published a resolution stating that anyone wishing to enter the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR) would need a visa in their passport. 5From now on, the only foreigners allowed to cross into Soviet Russia were those whose passports had been approved by the sole Soviet representative abroad: Vatslav Vorovsky, who was based in Stockholm. Three days later, the People’s Commissar of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD RSFSR), 6Grigory Petrovsky, issued an order forbidding ‘until further notice’ exit from the RSFSR without the permission of the local Soviets (Councils) for any citizen of a country that had been fighting against Russia. 7

In his study of isolationism in the Soviet state, Yury Felshtinsky wrote:

This was a timid and cautious step by the inexperienced Soviet authorities. Towards the end of December 1917, they devised such positions on entry to and exit from the country as had never been known, neither in Russia, nor in Europe. Here, all at once, there were passports with photographs, and the appropriate stamps, and special permits with special signatures, special representatives of both the NKVD (internal affairs) and the NKID (foreign affairs); here provision was made to carry out searches and personal examinations of everyone, including women, old people and children. At least they followed international norms and made an exception for diplomats. 8

In the first few years after the Revolution, the displacement of a huge mass of the population, through those wanting to resettle, refugees and emigrants, led to a complete collapse of control over migration. Many of these people had no documents at all that could confirm their identity. The Main Directorate of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Militia even had to issue a special circular, ‘What to Do With People Held for Not Having Papers’. It was addressed to all the heads of the militia’s regional directorates:

Under the tsarist regime, passports served only as a residence permit (Article 1 of the ‘Regulation on Passports’). Because of this there were various constraints on the population in terms of freedom of movement when searching for employment etc. At the present time, under the freedom of movement for citizens which has been recognized by the Soviet authorities, a passport or other residence permit (such as an employment book) can suffice as an identity document. And no-one should suffer repression or arrest for not having papers, as long as they do not belong to counter-revolutionary elements and if they do not have unserved criminal sentences or if there is no evidence of them avoiding military service. On the other hand, the militia should, without hindrance, provide written proof of identity to people who do not have it if they can show some appropriate evidence of their identity, including witness statements. 10

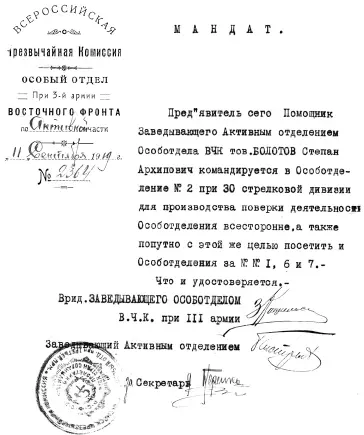

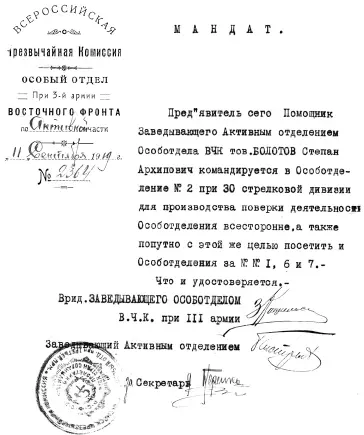

Figure 2 :Warrant for Stepan Arkhipovich Bolotov to inspect the activity of the Special Department of the VeCheKa 9attached to the 3rd Army of the Eastern Front in 1919, during the Civil War.

(Source: http://stopgulag.org.)

A wide variety of organizations had to issue all sorts of certificates for ‘working elements’. They divided into two types: ‘permanent’ and ‘special’. The permanent ones were meant to be the equivalent of identity documents. The special ones, or warrants (see figure 2), were issued by Party, government or military organizations to senior officials who had to travel from one place to another. They had a dual task: to confirm both the identity of the bearer and their authority. These warrants did not have a standard form, but as a rule they included the name, patronymic and surname of the bearer; their position in whichever organization had issued the warrant; the purpose of their mission; and their authority.

The first step towards the re-establishment of a means of registering the population was the Decree of the Council of People’s Commissars [Russ: Sovnarkom or SNK] of the RSFSR of 5 October 1918, ‘On Employment Books for Non-Working People’. 11The publication of this Decree had been preceded in July of that year by the passing of the first Soviet Constitution. In paragraph ‘f’ of Article 3 of the Constitution, it states: ‘Universal obligation to work is introduced for the purpose of eliminating the parasitic strata of society and organizing the economic life of the country’. Article 18 of the Constitution declares: ‘The Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic considers work the duty of every citizen of the Republic, and proclaims as its motto: “He shall not eat who does not work.”’ 12In this context, the document, which showed a citizen had fulfilled their work obligation, had every chance of becoming the basic document for the Soviet person. This was exactly what was planned for the employment book. In the ‘Decree on Employment Books’ it is stated that since labour is the duty of every citizen of the republic, employment records will be used in place of passports and other identity documents (‘Article 1: To introduce employment books in place of the previous identity documents, passports and so forth’). 13

It may seem strange that the first employment books were intended not for working people, but specifically for ‘non-working elements’. This was because first and foremost the Soviet authorities were concerned to observe the principle of the universal obligation to work. It was assumed that the victorious proletariat would observe this principle, but that the ‘non-working people’ would need to be put under special control. According to the Decree, this included the following categories:

1 those who lived on money not earned from labour, such as rental income or interest from capital;

2 people engaging in hired labour in order to make a profit;

3 members of the boards of corporations, companies or any kind of association, as well as the directors of such companies;

4 private traders, stockbrokers or any trading or commercial agents;

5 freelancers, if they are not performing any function deemed useful for society;

6 all those who do not have a clearly defined occupation, such as former army officers, cadets from military schools and colleges, former barristers and their assistants, private lawyers and other people in this category. 14

All of the above categories were obliged to have an employment book, in which at least once a month details were entered about how they had carried out the ‘social work and obligations’ they had been given (this might be clearing the streets of snow, chopping wood or such like). Those who were not engaged in socially useful work had to report to the militia every week, where a mark would be made in the allotted place in the employment record.

Because the employment book had the status of the basic document for ‘non-working people’, if someone did not have one it was not possible to move about the country nor, more importantly, receive ration cards. In the prevailing conditions, this threatened them with starvation. 15In Article 5 of the Decree, it states, ‘Only on production of an employment book … do the non-working elements have the right to move or to travel, both on the territory of the Soviet Republic and within the confines of each settlement; and the right to receive ration cards.’ 16In Article 8 it underlines once more that the employment book is their basic, and indeed only, legitimate personal document: ‘The employment book must be shown whenever an identity document is demanded.’ The Decree ends with an indication of the punishment that will follow should a non-valid identity document be produced: ‘People who fall into the category outlined in Article 1 and who are not entitled by the terms of this Decree to receive an employment book in exchange for a passport, or who produce false information about themselves or their activities, are liable to a fine of up to 10,000 roubles or a prison term of up to six months.’ 17Paradoxically, ‘reliable evidence’ could be supported only by the old documents, which had been declared to be no longer valid.

Читать дальше