Hippolyte Taine - History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Hippolyte Taine - History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3) — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

How did this grand and just conception originate? Doubtless common-sense and genius, too, were necessary to its production; but neither common-sense nor genius was lacking to men: there had been more than one who, observing, like Bacon, the progress of particular industries, could, like him, have conceived of universal industry, and from certain limited ameliorations have advanced to unlimited amelioration. Here we see the power of connection; men think they do everything by their individual thought, and they can do nothing without the assistance of the thoughts of their neighbors; they fancy that they are following the small voice within them, but they only hear it because it is swelled by the thousand buzzing and imperious voices, which, issuing from all surrounding or distant circumstances, are confounded with it in an harmonious vibration. Generally they hear it, as Bacon did, from the first moment of reflection; but it had become inaudible among the opposing sounds which came from without to smother it. Could this confidence in the infinite enlargement of human power, this glorious idea of the universal conquest of nature, this firm hope in the continual increase of well-being and happiness, have germinated, grown, occupied an intelligence entirely, and thence have struck its roots, been propagated and spread over neighboring intelligences, in a time of discouragement and decay, when men believed the end of the world at hand, when things were falling into ruin about them, when Christian mysticism, as in the first centuries, ecclesiastical tyranny, as in the fourteenth century, were convincing them of their impotence, by perverting their intellectual efforts and curtailing their liberty. On the contrary, such hopes must then have seemed to be outbursts of pride, or suggestions of the carnal mind. They did seem so; and the last representatives of ancient science, and the first of the new, were exiled or imprisoned, assassinated or burned. In order to be developed an idea must be in harmony with surrounding civilization; before man can expect to attain the dominion over nature, or attempts to improve his condition, amelioration must have begun on all sides, industries have increased, knowledge have been accumulated, the arts expanded, a hundred thousand irrefutable witnesses must have come incessantly to give proof of his power and assurance of his progress. The "masculine birth of the time" ( temporis partus masculus ) is the title which Bacon applies to his work, and it is a true one. In fact, the whole age co-operated in it; by this creation it was finished. The consciousness of human power and prosperity gave to the Renaissance its first energy, its ideal, its poetic materials, its distinguishing features; and now it furnishes it with its final expression, its scientific doctrine, and its ultimate object.

We may add also, its method. For, the end of a journey once determined, the route is laid down, since the end always determines the route; when the point to be reached is changed, the path of approach is changed, and science, varying its object, varies also its method. So long as it limited its effort to the satisfying an idle curiosity, opening out speculative vistas, establishing a sort of opera in speculative minds, it could launch out any moment into metaphysical abstractions and distinctions: it was enough for it to skim over experience; it soon quitted it, and came all at once upon great words, quiddities, the principle of individuation, final causes. Half proofs sufficed science; at bottom it did not care to establish a truth, but to get an opinion; and its instrument, the syllogism, was serviceable only for refutations, not for discoveries; it took general laws for a starting-point instead of a point of arrival; instead of going to find them, it fancied them found. The syllogism was good in the schools, not in nature; it made disputants, not discoverers. From the moment that science had art for an end, and men studied in order to act, all was transformed; for we cannot act without certain and precise knowledge. Forces, before they can be employed, must be measured and verified; before we can build a house, we must know exactly the resistance of the beams, or the house will collapse; before we can cure a sick man, we must know with certainty the effect of a remedy, or the patient will die. Practice makes certainty and exactitude a necessity to science, because practice is impossible when it has nothing to lean upon but guesses and approximations. How can we eliminate guesses and approximations? How introduce into science, solidity and precision? We must imitate the cases in which science, issuing in practice, has proved to be precise and certain, and these cases are the industries. We must, as in the industries, observe, essay, grope about, verify, keep our mind fixed on sensible and particular things, advance to general rules only step by step; not anticipate experience, but follow it; not imagine nature, but interpret it. For every general effect, such as heat, whiteness, hardness, liquidity, we must seek a general condition, so that in producing the condition we may produce the effect. And for this it is necessary, by fit rejections and exclusions, to extract the condition sought from the heap of facts in which it lies buried, construct the table of cases from which the effect is absent, the table where it is present, the table where the effect is shown in various degrees, so as to isolate and bring to light the condition which produced it. [390]Then we shall have, not useless universal axioms, but efficacious mediate axioms, true laws from which we can derive works, and which are the sources of power in the same degree as the sources of light. [391]Bacon described and predicted in this modern science and industry, their correspondence, method, resources, principle; and after more than two centuries it is still to him that we go even at the present day to look for the theory of what we are attempting and doing.

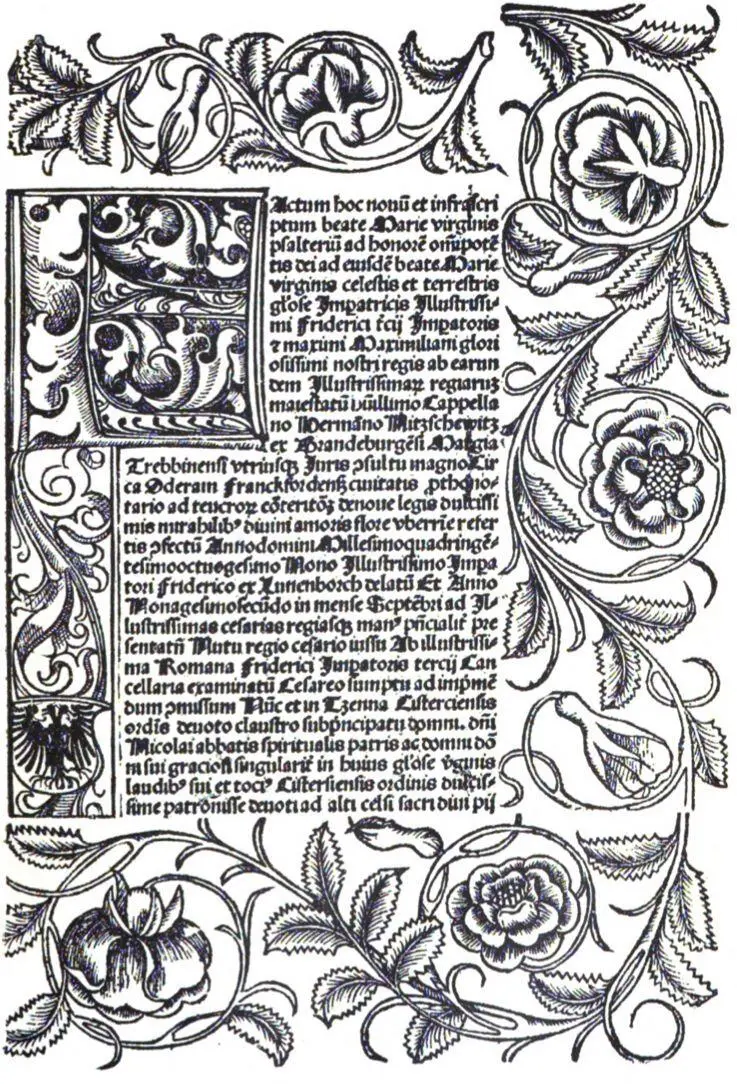

CHOICE EXAMPLES OF EARLY PRINTING AND ENGRAVING.

Fac-similes from Rare and Curious Books.

THE NEW PSALTER OF THE VIRGIN MARY.

The "Novum Beatæ Mariæ Virginis Psalterium" was printed by the Cistercians monks of the monastery of Sienna, in the duchy of Magdeburg, near Wittemberg, in 1492. The present illustration shows the page of dedication, in which mention is made of the Emperor Frederick, whose arms, the double-headed eagle, appears in the border. The book was printed in the year before the emperor died. The border is an easy and flowing design of roses, which are always considered an emblem of the Virgin. The volume is a remarkable production, rare and much prized by collectors.

Beyond this great view, he has discovered nothing. Cowley, one of his admirers, rightly said that, like Moses on Mount Pisgah, he was the first to announce the promised land; but he might have added quite as justly, that, like Moses, he did not enter there. He pointed out the route, but did not travel it; he taught men how to discover natural laws, but discovered none. His definition of heat is extremely imperfect. His "Natural History" is full of fanciful explanations. [392]Like the poets, he peoples nature with instincts and desires; attributes to bodies an actual voracity, to the atmosphere a thirst for light, sounds, odors, vapors which it drinks in; to metals a sort of haste to be incorporated with acids. He explains the duration of the bubbles of air which float on the surface of liquids, by supposing that air has a very small or no appetite for height. He sees in every quality, weight, ductility, hardness, a distinct essence which has its special cause; so that when a man knows the cause of every quality of gold, he will be able to put all these causes together, and make gold. In the main, with the alchemists, Paracelsus and Gilbert, Kepler himself, with all the men of his time, men of imagination, nourished on Aristotle, he represents nature as a compound of secret and living energies, inexplicable and primordial forces, distinct and indecomposable essences, adapted each by the will of the Creator to produce a distinct effect. He almost saw souls endowed with latent repugnances and occult inclinations, which aspire to or resist certain directions, certain mixtures, and certain localities. On this account also he confounds everything in his researches in an undistinguishable mass, vegetative and medicinal properties, mechanical and curative, physical and moral, without considering the most complex as depending on the simplest, but each on the contrary in itself, and taken apart, as an irreducible and independent existence. Obstinate in this error, the thinkers of the age mark time without advancing. They see clearly with Bacon the wide field of discovery, but they cannot enter upon it. They want an idea, and for want of this idea they do not advance. The disposition of mind which but now was a lever, is become an obstacle: it must be changed, that the obstacle may be got rid of. For ideas, I mean great and efficacious ones, do not come at will nor by chance, by the effort of an individual, or by a happy accident. Methods and philosophies, as well as literatures and religions, arise from the spirit of the age; and this spirit of the age makes them potent or powerless. One state of public intelligence excludes a certain kind of literature; another, a certain scientific conception. When it happens thus, writers and thinkers labor in vain, the literature is abortive, the conception does not make its appearance. In vain they turn one way and another, trying to remove the weight which hinders them; something stronger than themselves paralyzes their hands and frustrates their endeavors. The central pivot of the vast wheel on which human affairs move must be displaced one notch, that all may move with its motion. At this moment the pivot was moved, and thus a revolution of the great wheel begins, bringing round a new conception of nature, and in consequence that part of the method which was lacking. To the diviners, the creators, the comprehensive and impassioned minds who seized objects in a lump and in masses, succeeded the discursive thinkers, the systematic thinkers, the graduated and clear logicians, who, disposing ideas in continuous series, lead the hearer gradually from the simple to the most complex by easy and unbroken paths. Descartes superseded Bacon; the classical age obliterated the Renaissance; poetry and lofty imagination gave way before rhetoric, eloquence, and analysis. In this transformation of mind, ideas were transformed. Everything was drained dry and simplified. The universe, like all else, was reduced to two or three notions; and the conception of nature, which was poetical, became mechanical. Instead of souls, living forces, repugnances, and attractions, we have pulleys, levers, impelling forces. The world, which seemed a mass of instinctive powers, is now like a mere machinery of cog-wheels. Beneath this adventurous supposition lies a large and certain truth; that there is, namely, a scale of facts, some at the summit very complex, others at the base very simple; those above having their origin in those below, so that the lower ones explain the higher; and that we must seek the primary laws of things in the laws of motion. The search was made, and Galileo found them. Thenceforth the work of the Renaissance, outstripping the extreme point to which Bacon had pushed it, and at which he had left it, was able to proceed onward by itself, and did so proceed, without limit.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «History of English Literature (Vol. 1-3)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.