On the other hand, Espriu had the familiarity with Anglophone literatures to be expected in a well-read, erudite man. Probably more, according to Francesc Vallverdú, one of Espriu’s closest friends and collaborators: ‘I was continually amazed by his knowledge of contemporary writers (he read both English and French with ease).’ 10 In 1985, Antoni Batista asked the poet what books he wished he had written. The only two English works he mentioned were Utopia , by Thomas More and The Origin of Species , by Charles Darwin. 11 However, although somewhat anecdotal, there are a number of Anglo-American cultural references in Espriu’s poetry: the lyrical speaker of ‘Cançó de Tipsy Jones’ is an English pirate, ‘Veient Rosie a la finestra’ tells of an American soldier marching off to war and ‘La princesa del Iang-tsé’ is grotesquely dedicated to Mrs Banks, who domesticates fleas (these three poems are from Cançons d’Ariadna ); and what is more, the hanged man has an English name in ‘Knowles, el penjat’ ( El caminat i el mur ). 12 Espriu’s appreciation of English or American classics may also take the form of quotation. In ‘El corb’ ( Cançons d’Ariadna ), the phrase ‘Mai més’ obviously echoes Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Raven.’ In Mrs Death , the opening epigraph is from William Shakespeare’s Cymbeline : ‘Whiles yet the dew’s on ground, gather those flowers’ (I.6).

In an interview with Salvador Pàniker, the latter puts forward Paul Valéry as Espriu’s French counterpart. Espriu accepts the comparison, but being ‘un hombre de formación clásica,’ which contributes decisively to shaping his work, he sees it as closer to that of James Joyce: ‘En otros países también hay casos de la misma preocupación. Joyce por ejemplo. Pero se trata de escritores de mucha más talla que yo.’ 13 The concern that Espriu refers to is nothing but the aim of the mythical method, and works by James Joyce and T. S. Eliot are textbook examples of its application. For the latter, the purpose of the mythical method should be ‘the exploration of worlds of otherness [including ancient myth] in quest for the spiritual foundations of the modern self.’ 14

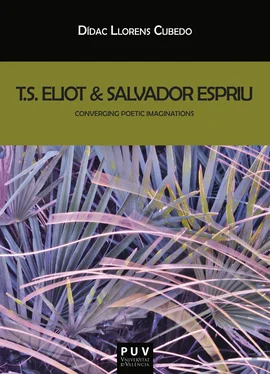

Espriu was more acquainted with cultures of English expression than Eliot could be with a minority language and its literature, for obvious reasons. Although both poets knew, to different degrees, about their respective traditions, there is no evidence as to their mutual influence. According to Albert Manent, Eliot’s poetry was an essential reference for a number of Catalan poets, writing in Spanish or Catalan, from the 1940s onwards. Jaime Gil the Biedma was mentioned above; his indebtedness to Eliot is easily discernible and has been the object of research. 15 Among the poets of Catalan expression, Manent mentions Carles Riba, Pere Gimferrer and Narcís Comadira, but not Espriu (‘T. S. Eliot a Catalunya,’ p. 73). 16

Espriu was familiar with Eliot’s poetry, as we know from his ‘Fitxer d’Aprenentatge.’ In this reading file, which the Catalan poet kept during his youth, Eliot and his key titles are listed under the heading ‘poetes nord-americans a recordar.’ 17 On the occasion of Eliot’s death in 1965, Manent asked a number of Catalan poets to answer two questions about the Anglo-American author: ‘¿Com veieu la poesia de T. S. Eliot dins la poesia contemporània?’ and ‘¿Què ha representat per a vós la poesia de T. S. Eliot?’ The answers would be in the form of an appreciation, to be published in the journal Serra d’Or . Manent claims that Eliot ‘ha tingut entre els nostres lectors i escriptors alguna cosa més que una vaga nomenada’ and explains that the contributors are ‘poetes d’avantguerra als quals havia interessat—o podia haver interessat—l’obra del poeta i humanista anglés.’ One of these was Salvador Espriu who, characteristically, answered the two questions in only five words: to the first, his answer was ‘com a molt important’ and to the second ‘res.’ 18

Espriu’s laconic answers are coherent with his systematic rejection of influences, based on his uneasiness that his work might be misinterpreted. 19 He did acknowledge, however an ‘unproblematic’ source of influence on his poetry: ‘Potser serà pretensiós el que jo li vaig a dir, però pel que respecta a la poesia crec que no m’ha influït ningú, si no és potser la Bíblia’ (Batista, p. 38).

In The Anxiety of Influence , Harold Bloom quotes lines by Wallace Stevens where he, like Espriu, does not declare his indebtedness to the work of any previous poet, including Eliot. 20 Stevens’s dismissive denial of any influence whatsoever is put forward by Bloom as confirmation that the weight of tradition is certain to produce anxiety in poets whom he calls ‘strong’ (p. 6). In Bloom’s theory of poetry, influence is the motivating power of poetic history, which evolves as poets receive ( misread ) the work of those poets who preceded them: ‘strong poets make that history by misreading one another, so as to clear imaginative space for themselves’ (p. 5). This notion of poetic history is parallel to Eliot’s idea—expressed in the essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’—that literary works of merit result from the interaction between poets’ creative powers and the poetry of the past. 21 Like Eliot, Bloom suspects poets who boast the denial of this interaction. The latter’s statement that ‘weaker talents idealize; figures of capable imagination appropriate for themselves’ (p. 5) is almost a paraphrase of Eliot’s celebrated axiom ‘immature poets imitate, mature poets steal.’ 22

The comparative nature of the present work does not develop, therefore, from the certainty of influence, but from the initial recognition of parallelisms between the productions of the two authors. Susan Bassnett has referred to this intuitive awareness as determining the adoption of a comparative approach: ‘a reader may be impelled to follow up what appear to be similarities between texts or authors from different cultural contexts.’ 23 This study constitutes an exercise of comparative literature that would conform to at least two characteristics of the field, as defined by Bassnett (p. 1). First, it ‘involves the study of texts across cultures’ (although Espriu and Eliot could be regarded as representative authors of a unified European or Western culture, it is of course equally valid to state that they belong to two different European cultures). Second, it is ‘concerned with patterns of connection in literatures across both time and space’ (although Eliot and Espriu are, practically speaking, contemporaries, the study of their works inevitably involves other works from different periods).

The present work exemplifies one of the basic roles of comparative literature: namely, raising awareness of connections between texts that would perhaps go unnoticed in national literature studies. The detection, description and analysis of intertextual evidence has two interrelated results: cultural affinities, similarities across time and space, emerge; furthermore, the study of authors from a comparative perspective causes them to be perceived differently, new knowledge about them being gained. 24 Connections and parallelisms are unveiled by comparison, presupposing a vision of literature as a whole whose parts are—although not always evidently—interrelated. This implication is compatible with Northrop Frye’s archetypal structuralism, which is an important component of the theoretical and critical basis underpinning this study.

Northrop Frye ‘looks at the literature of all times as “a total form” and examines works of art not in isolation but within this formal universe, as potentially relevant to “the total cultural form of our present life.”’ 25 Frye’s objective is to discern a ‘co-ordinating principle’ underlying and uniting the totality of literary works. This can be achieved through the study of archetypes, which ‘enables us to perceive the shared myths that literary works rely on and explore: through that awareness we can glimpse the underlying structure of the structures of all works.’ 26

Читать дальше