Washington Irving - The Alhambra

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Washington Irving - The Alhambra» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Alhambra

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Alhambra: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Alhambra»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Alhambra — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Alhambra», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I forbear for the present, however, to describe the other delightful apartments of the palace. My object is merely to give the reader a general introduction into an abode where, if so disposed, he may linger and loiter with me day by day until we gradually become familiar with all its localities.

NOTE ON MORISCO ARCHITECTURE

To an unpractised eye the light relievos and fanciful arabesques which cover the walls of the Alhambra appear to have been sculptured by the hand, with a minute and patient labor, an inexhaustible variety of detail, yet a general uniformity and harmony of design truly astonishing; and this may especially be said of the vaults and cupolas, which are wrought like honey-combs, or frostwork, with stalactites and pendants which confound the beholder with the seeming intricacy of their patterns. The astonishment ceases, however, when it is discovered that this is all stucco-work; plates of plaster of Paris, cast in moulds and skilfully joined so as to form patterns of every size and form. This mode of diapering walls with arabesques, and stuccoing the vaults with grotto-work, was invented in Damascus, but highly improved by the Moors in Morocco, to whom Saracenic architecture owes its most graceful and fanciful details. The process by which all this fairy tracery was produced was ingeniously simple. The wall in its naked state was divided off by lines crossing at right angles, such as artists use in copying a picture; over these were drawn a succession of intersecting segments of circles. By the aid of these the artists could work with celerity and certainty, and from the mere intersection of the plain and curved lines arose the interminable variety of patterns and the general uniformity of their character.[3]

Much gilding was used in the stucco-work, especially of the cupolas; and the interstices were delicately pencilled with brilliant colors, such as vermilion and lapis lazuli, laid on with the whites of eggs. The primitive colors alone were used, says Ford, by the Egyptians, Greeks, and Arabs, in the early period of art; and they prevail in the Alhambra whenever the artist has been Arabic or Moorish. It is remarkable how much of their original brilliancy remains after the lapse of several centuries.

The lower part of the walls in the saloons, to the height of several feet, is incrusted with glazed tiles, joined like the plates of stucco-work, so as to form various patterns. On some of them are emblazoned the escutcheons of the Moslem kings, traversed with a band and motto. These glazed tiles (azulejos in Spanish, az-zulaj in Arabic) are of Oriental origin; their coolness, cleanliness, and freedom from vermin, render them admirably fitted in sultry climates for paving halls and fountains, incrusting bathing-rooms, and lining the walls of chambers. Ford is inclined to give them great antiquity. From their prevailing colors, sapphire and blue, he deduces that they may have formed the kind of pavements alluded to in the sacred Scriptures:—“There was under his feet as it were a paved work of a sapphire stone” (Exod. xxiv. 10); and again, “Behold I will lay thy stones with fair colors, and lay thy foundations with sapphires” (Isaiah liv. 11).

These glazed or porcelain tiles were introduced into Spain at an early date by the Moslems. Some are to be seen among the Moorish ruins which have been there upwards of eight centuries. Manufactures of them still exist in the Peninsula, and they are much used in the best Spanish houses, especially in the southern provinces, for paving and lining the summer apartments.

The Spaniards introduced them into the Netherlands when they had possession of that country. The people of Holland adopted them with avidity, as wonderfully suited to their passion for household cleanliness; and thus these Oriental inventions, the azulejos of the Spanish, the az-zulaj of the Arabs, have come to be commonly known as Dutch tiles.

IMPORTANT NEGOTIATIONS

THE AUTHOR SUCCEEDS TO THE THRONE OF BOABDIL

THE day was nearly spent before we could tear ourself from this region of poetry and romance to descend to the city and return to the forlorn realities of a Spanish posada. In a visit of ceremony to the Governor of the Alhambra, to whom we had brought letters, we dwelt with enthusiasm on the scenes we had witnessed, and could not but express surprise that he should reside in the city when he had such a paradise at his command. He pleaded the inconvenience of a residence in the palace from its situation on the crest of a hill, distant from the seat of business and the resorts of social intercourse. It did very well for monarchs, who often had need of castle walls to defend them from their own subjects. “But, señors,” added he, smiling, “if you think a residence there so desirable, my apartments in the Alhambra are at your service.”

It is a common and almost indispensable point of politeness in a Spaniard, to tell you his house is yours.—“Esta casa es siempre à la disposicion de Vm.”—“This house is always at the command of your Grace.” In fact, anything of his which you admire, is immediately offered to you. It is equally a mark of good breeding in you not to accept it; so we merely bowed our acknowledgments of the courtesy of the Governor in offering us a royal palace. We were mistaken, however. The Governor was in earnest. “You will find a rambling set of empty, unfurnished rooms,” said he; “but Tia Antonia, who has charge of the palace, may be able to put them in some kind of order, and to take care of you while you are there. If you can make any arrangement with her for your accommodation, and are content with scanty fare in a royal abode, the palace of King Chico is at your service.”

We took the Governor at his word, and hastened up the steep Calle de los Gomeres, and through the Great Gate of Justice, to negotiate with Dame Antonia,—doubting at times if this were not a dream, and fearing at times that the sage Dueña of the fortress might be slow to capitulate. We knew we had one friend at least in the garrison, who would be in our favor, the bright-eyed little Dolores, whose good graces we had propitiated on our first visit; and who hailed our return to the palace with her brightest looks.

All, however, went smoothly. The good Tia Antonia had a little furniture to put in the rooms, but it was of the commonest kind. We assured her we could bivouac on the floor. She could supply our table, but only in her own simple way;—we wanted nothing better. Her niece, Dolores, would wait upon us; and at the word we threw up our hats and the bargain was complete.

The very next day we took up our abode in the palace, and never did sovereigns share a divided throne with more perfect harmony. Several days passed by like a dream, when my worthy associate, being summoned to Madrid on diplomatic duties, was compelled to abdicate, leaving me sole monarch of this shadowy realm. For myself, being in a manner a hap-hazard loiterer about the world, and prone to linger in its pleasant places, here have I been suffering day by day to steal away unheeded, spell-bound, for aught I know, in this old enchanted pile. Having always a companionable feeling for my reader, and being prone to live with him on confidential terms, I shall make it a point to communicate to him my reveries and researches during this state of delicious thraldom. If they have the power of imparting to his imagination any of the witching charms of the place, he will not repine at lingering with me for a season in the legendary halls of the Alhambra.

And first it is proper to give him some idea of my domestic arrangements: they are rather of a simple kind for the occupant of a regal palace; but I trust they will be less liable to disastrous reverses than those of my royal predecessors.

My quarters are at one end of the Governor’s apartment, a suite of empty chambers, in front of the palace, looking out upon the great esplanade called la plaza de los algibes (the place of the cisterns); the apartment is modern, but the end opposite to my sleeping-room communicates with a cluster of little chambers, partly Moorish, partly Spanish, allotted to the châtelaine Doña Antonia and her family. In consideration of keeping the palace in order, the good dame is allowed all the perquisites received from visitors, and all the produce of the gardens; excepting that she is expected to pay an occasional tribute of fruits and flowers to the Governor. Her family consists of a nephew and niece, the children of two different brothers. The nephew, Manuel Molina, is a young man of sterling worth and Spanish gravity. He had served in the army, both in Spain and the West Indies, but is now studying medicine in the hope of one day or other becoming physician to the fortress, a post worth at least one hundred and forty dollars a year. The niece is the plump little black-eyed Dolores already mentioned; and who, it is said, will one day inherit all her aunt’s possessions, consisting of certain petty tenements in the fortress, in a somewhat ruinous condition it is true, but which, I am privately assured by Mateo Ximenes, yield a revenue of nearly one hundred and fifty dollars; so that she is quite an heiress in the eyes of the ragged son of the Alhambra. I am also informed by the same observant and authentic personage, that a quiet courtship is going on between the discreet Manuel and his bright-eyed cousin, and that nothing is wanting to enable them to join their hands and expectations but his doctor’s diploma, and a dispensation from the Pope on account of their consanguinity.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

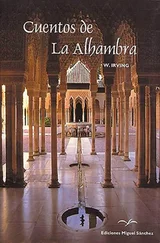

Похожие книги на «The Alhambra»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Alhambra» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Alhambra» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.