Eric A. Eliason proposes a different label: Mormon Magical Realism. He is talking about a group of contemporary writers in which he includes the work by Margaret Blair Young, Orson Scott Card, Levi S. Peterson and Barber (Eliason 40-45). Eliason states that Barber fictionalizes Mormon vision of the “mundane world” and “the world of visions and spirits” (Eliason 40-45) as one. He says that “most of the stories that are not fantastic at face value at least leave the reader wondering at the reality of strange visions and touched by their haunting presence” (Eliason 40-45). My interpretation of Barber’s technique and intention when dealing with this world of vision and spirits is different from Eliason’s. When he says that “Mormon magical realism allows for the reality of sacred experience and the possibility of bumping into beings of light” (Eliason 40-45), I agree with him, but I perceive a complexity that, as I explain in my analysis of Parting the Veil: Stories from a Mormon Imagination , opens up a broad range of possible interpretations.

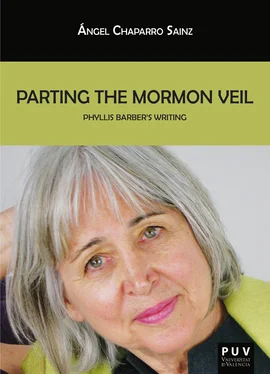

There has always been a tendency to classify Mormon literature in two isolated categories, depending on its mission or appeal. In my introduction to Mormon literature, I explain the opposing definitions that some Mormon scholars employ to establish two different lines in Mormon literature. Lavina Fielding Anderson follows the same tendency to establish her own classification of Mormon literature. She outlines a definition that follows a long tradition and classifies Margaret Blair Young, Linda Sillitoe and Barber within that frame. Specifically talking about Barber, Anderson considers that the category in which she could be included is the one she labels insider/outsider—a category that, in Anderson’s words, requires “the trickiest balance, the most demanding standards and the highest stakes” ( Masks 1). Anderson’s analysis of Barber’s fiction concludes that she fits into this category due to her ability to appeal to different audiences. Even though Anderson states that And the Desert Shall Blossom “shows Barber as a gifted interpreter of Mormonism as an insider, as someone for whom the signs, symbols, and shibboleths of Mormonism make a fabric of wholeness and coherence” ( Masks 1), she also says that “most of Phyllis Barber’s short stories that she published in The School of Love are not explicitly Mormon. Most of them are experimental, highly impressionistic, symbols, dreams, and fragments of nightmares” ( Masks 1).

Barber embraces this challenge to be spiritual and experiential, to address Mormons and non-Mormons. She departs from Las Vegas and the Mormon ward 6to walk far—and observe, experience and learn—but always with “a stitch on my side” ( Precarious 120), always aware of the place she departed from. This movement helps me to detect the meaningful information that I need to understand Barber’s fiction. As Denis Cosgrove and Mona Domosh say, “when we write our geographies we are not just representing some reality, we are creating meaning” (35).

Barber deals with Mormon themes without avoiding the attributes of postmodernism and the wide range of possibilities that literature gives her. Barber admits the influence of having been a student of François Camoin at the University of Utah, and she confesses her taste for postmodern techniques: “I like to explore time warps, the edges of sanity, impressionism, experimental language, oblique approaches to the subject of humanity” (Barber, Mormon 118). She applies properties of modern literature to her work, while never becoming separated from her origins: she can deal with Mormon ideas—or develop Mormon stories—but always playing with irony, perspective, chronology, symbolism, structure, and many other techniques that help her literature attain a postmodernist flair. She multiplies meanings. She avoids resorting to stereotypes or providing conclusive endings. The use of those devices is basically secondary though. It would be too shallow to try to analyze irony, perspective, chronology, and fragmentation in Barber only to achieve the purpose of fitting her fiction within the frame of postmodern literature. Those devices are consequences rather than primary resources.

Postmodernism in Barber, rather than a set of literary devices, is a personal commitment that opens a wider approach to Mormonism: “a mixture of doubt and belief, transgression and faith” (Bush, Faithful 192). This position is rather ideological, and it needs to be separated from the technical fragmentation—the elusiveness—of her linear structure; the play with tenses; the irony, and the changes on perspective that she uses to make more complex her narrative. Barber, like many other writers, proposes a different picture of Mormonism, a contemporary picture in which urban, complex and modern conflicts play an important role in the plot, and in the construction of the fictional characters. This, as Elizabeth Breau explains in her recent review of Raw Edges , propels Barber into a wider audience: “her empathy and ability to articulate the emotions of divorce, loss, and struggle render her more than simply a regional or Mormon author, but an author of national scope” (1).

Besides, one of Barber’s most valuable attributes is her integrity and bravery when applying on the page her highly committed and frank conception of literature. She is a writer who disagrees with conclusive divisions, who has a taste for “no easy blacks and whites” (Barber, Mormon 109). Barber challenges dichotomies such as good versus evil—black versus white—so ordinary in religious belief. In her fiction, there usually is no resolution or closure—Barber’s books have no closing end; the reader is left with more questions than answers. In her review of Darrell Spencer’s CAUTION: Men in Trees , Barber recognizes her own philosophy: “Spencer is an excellent commentator on the pop-eyed condition of contemporary life, which, after all, is too diverse to reduce to any one explanation” ( CAUTION 191). The same criterion applies to her work.

Barber is aware of the possible response that certain perspectives can motivate among some Mormons. Her resolution to dwell in a middle ground, embracing risk and hesitation—questioning and discovery—is a potential source for rejection. When talking about Levi Peterson and his famous novel The Backslider , Barber states: “These writers need to remember that making any choice includes the price of admission: there’s a price / prize for belonging and remaining safe; there’s a price / prize for living at the edge” ( Mormon 113). In this quotation, she appears to be talking to herself, rather than advising Peterson. Barber is subtly referring to the imbalance between the praise she received and the price she paid. Behind those words, I sense how she is trying to negotiate the disturbing acceptance of her professional success—but also of her failure.

Karl Keller explains in “On Words and the Word of God” how literature is “essentially anarchic, rebellious, shocking, analytical, critical, deviant, absurd, subversive, destructive” ( On 20). Keller is highly pessimistic and critical of any connection between religion and literature: “literature is seldom written, and can be seldom written, in the service of religion” ( On 17). I believe that he could have changed his mind by reading Barber. Barber has dwelled—and wandered—in that place that Robert Raleigh describes in his introduction to In Our Lovely Deseret: Mormon Fictions :

Like any religious culture, however, there are those who live near that warm, beating heart, those who reside in the vicinity of the brain, and those who live somewhere farther out on the periphery, closer to the hard, sharp edges of the world. This collection of stories is mostly about people who live somewhere nearer the periphery of the “body of Christ”—people who can’t or won’t quite fit into a culture where fitting is one of the highest values. (Raleigh vii)

Читать дальше