4Zion may have different meanings within Mormonism but here it refers to the utopian project to organize a settlement based on communitarian economics.

51838 Mormon War and Missouri Mormon War are also names used to refer to these hostilities. Thus scholars and historians try to differentiate it from the lesser known conflicts that took place in Illinois, and from the so-called Utah War that lasted from May 1857 until July 1858.

6Historically Mormons were understood to be friendly to Native Americans. One important tenet of Mormon faith is rooted in the Mormon belief that Native Americans are the descendants of the original Israelites who came to America, as explained in the Book of Mormon . They aimed at being on good terms with Native Americans, but this did not always transpire, and the policy was a failure. Richard White explains how the Mormons followed the same pattern of appropriation so common in the pioneering of the American West: “In Utah, too, the Mormons established residence on Indian lands without any federal acquisition of title” (White, It’s 89). Another scholar, Jared Farmer, states that the conquest of Utah was different for its religious element, but that again they followed the same pattern that other pioneers had followed in other regions: “yet the main story of Utah’s formation—settlers, colonizing Indian land, organizing territory, dispossessing natives, and achieving statehood—could not be more American” (Farmer 14).

7“As the 1856 Republican Party platform put it, polygamy was, along with slavery, one of the last ‘twin relics of barbarism,’ a sentiment echoed by President Grant in 1871, who decried Mormons as ‘barbarians’ and ‘repugnant to civilization and decency’” (Handley, Marriage 101).

8Gentiles for the Mormons are those who are not Mormons.

9Using John L. Hart’s statistics, published in the LDS News at the end of the 20 thcentury (1997), William A. Wilson concludes: “Especially is that true today when most Mormons do not live in the West. Of today’s ten million Mormons only ten percent live in Utah, and over half of all Mormons live outside the United States and Canada” (189).

10I will show later that some Mormon scholars do not agree with this statement.

11This refers to James being an American writer writing in Europe.

12The original text published under the title “The Dawning of a Brighter Day: Mormon Literature After 150 years” was first reprinted in After 150 Years: The Latter-Day Saints in Sesquicentennial Perspective (1983), edited by Thomas G. Alexander and Jessie L. Embry. The one in Tending the Garden is an abbreviated version. In 1995, this article appeared in David J. Whittaker’s Mormon Americana: A Guide to Sources and Collections in the United States with the title “Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects”. With slight changes and updated, a web version of this last print version is available at Mormon Literature database.

13The Mormons believe in the Book of Mormon , hence their appellation. The Mormons accept as canonical scripture both the Bible and the Book of Mormon which is said to have been translated by Joseph Smith.

14I will be using this denomination as a label under which to gather all the novels published in the 19 thcentury that had some kind of reference to Mormonism from a negative point of view. I borrowed this term from Levi S. Peterson, who, in “Mormon Novels,” gives a rigorous chronological account of all these novels.

15His name is carved in the wall of honor in the Tower Entrance and Reception Gallery of the Mathewson-IGT Knowledge Center since 2010 when he was inducted into the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame.

16 A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints was the first published anthology in Mormon literature. Sillitoe’s emphasis is therefore significant even from an historical perspective: “[It] includes twelve men and four women in the section of nineteenth century poetry, but sixteen men and thirteen women in the twentieth century selection” ( New 47-48). In Fire in the Pasture women outnumber men.

17Richard Cracroft died in September 2012, when I was still working on this book. Eugene England, a prominent scholar himself, said about Richard Cracroft that he “could be called the father of modern Mormon literary studies for his pioneering work in the early 1970s” (England, Tending xiv).

PHYLLIS BARBER’S WRITING

Biographical and Cultural Background

Sometimes, I just avoid reading book covers. Mainly, because those covers are usually the reason why I pick a book off the shelf in a bookshop, or why I do not. Such whimsical and impulsive reasoning determines my choices more than I would like them to. Basically, if I feel the temptation to glance at the back cover to see the blurb of the writer’s life, it means that I am still hesitant about reading that book.

Sometimes though, I look at the back cover when I have already finished reading the book. On these occasions, the stimulus to look for that information about the writer has a totally different origin. Holden Caulfield, J.D. Salinger’s main character in The Catcher in the Rye , explains it quite well when he proposes a particular criterion to determine what he considers worthwhile literature: “What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it” (Salinger 16).

When I finished reading Barber’s How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir , I closed the book and read the back cover for the first time. I felt like smiling, but I also felt disappointed. This is what it says:

Phyllis Barber, a freelance writer and professional pianist, is on the faculty of Vermont College’s MFA in Writing Program. Her published works include And the Desert Shall Blossom , The School of Love , and two books for children. She was a first prize winner in the novel and short story categories in the 1988 Utah Fine Arts Literary Competition. 1

How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir is the biographical account of Barber’s girlhood and adolescence. In addition, it is a good example of what it meant to be a Mormon in Las Vegas in the 1950s and 1960s. When I was done reading the book, I felt like I had come closer to Barber. I felt like I had heard all her little secrets and that she had sincerely confessed all of them directly to me. So, when I read this brief summary of her life on the back cover, I felt disappointed: just three lines summarizing a few achievements? Is that all you can tell me about my nosy-parker Rhythmette ? Maybe I was looking for a phone number and that is why I felt disappointed.

Anyway, I did not despair but decided to make an inquiry in an organized manner, starting from the very beginning. The first adult book that Barber wrote, even though, prior to that, some of her short stories had been published in different magazines, was The School of Love in 1990. The School of Love is a collection of short stories. Each one of those thirteen stories contains a singular lesson in what love means. A wide array of loving possibilities will be developed in this collection. I turned my copy around to read the blurb:

Phyllis Barber holds a B.A. in music from San Jose University and the Goddard M.F.A. in writing from Vermont College. Born in Nevada, she has since 1970 lived mostly in Utah.

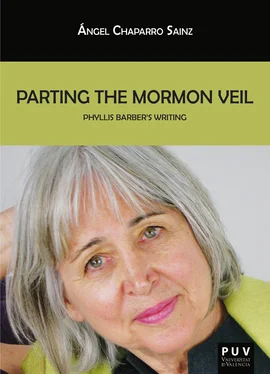

This biographical note happened to be even shorter than the first I read, but there are two main differences when comparing the two of them. To start with, there seemed to be no outstanding literary achievement—no prize, no award—when she published this book; so, first, I see the woman, then, the writer. I know that she holds degrees. I know that she studied music. I know that she moved from Nevada to Utah. Secondly, there is something else that I found in this book, but that I cannot quote: there is a photograph; a photograph where Barber smiles—laughs with all her heart, I envisage—and she wears a big, round earring and a colorful blouse—even if the picture is in black and white, I again envisage. My first glimpse turned out to be positive, not to say just poetically kaleidoscopic .

Читать дальше