Until the nineteenth century most of the world boundaries between states were not fixed. Most treaties were accords designed to prevent conflict or solidify alliances. Until the Treaty of Greenville (1795) in which annuities were institutionalized, treaties with the Indians of North America were primarily used to maintain a balance of power between France and England. After Greenville, the Louisiana Purchase (1803), the discovery of gold in Georgia (1828), and the initiation of Andrew Jackson’s policy of forced ethnic cleansing (1829), treaties were negotiated between the US and the indigenous population in order to acquire the land of the latter. In 1871 Congress stopped negotiating treaties, and by 1924 extended citizenship to American Indians.

Throughout all of this, because the Commerce Clause (Section 8) of the US Constitution reserved to the federal government the right to regulate commercial relationships and land ownership “… with the Indian Tribes,” questions and issues concerning the use and ownership of the lands of the native peoples was left up to the bureaucrats and politicians in Washington, D.C. to decide. This has been the situation from 1790 onward to today. 1

By the nineteenth century Europeans and Americans began to arrange treaties between themselves or with local rulers, and from the early to mid-nineteenth century mapmaking and the map were essential to this process. The survey maps of the General Land Office made relevant the shape of the territory, and that shape would eventually gain tremendous political importance.

Akin to the Cotton Kingdom, the Greater Southwest was surveyed and mapped before the conquering troops arrived, only to be followed by gold seekers, farmers, entrepreneurs, Protestant missionaries, and Mormon settlers. And the US government was very busy negotiating treaties with Mexicans, Navajos, Shoshones and others. Treaty-making had taken on a new role, that of paving the way for settlement and development of indigenous lands, and the formalization of the subordination of tribal peoples. While the treaties may have failed from the indigenous perspective, these accords did meet the needs of the newcomers. 9

The Indians, as obstacles to development, had to be removed. By mid-century the US government had already developed the concept of the reservation. Derived from English Indian policies, this treatment of segregating tribes in separate communities differed sharply from the Spanish and Mexican ideas of assimilation and incorporation of the Indian as a national citizen. In 1858, the commissioner of Indian Affairs described the reservation system this way: “concentrating the Indians on small reservations of land, and … sustaining them there for a limited period of time, until they can be induced to make the necessary exertions to support themselves.” 10

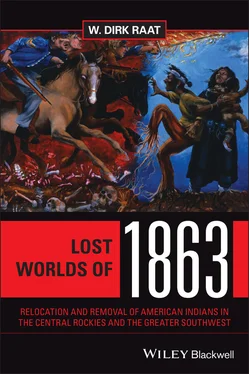

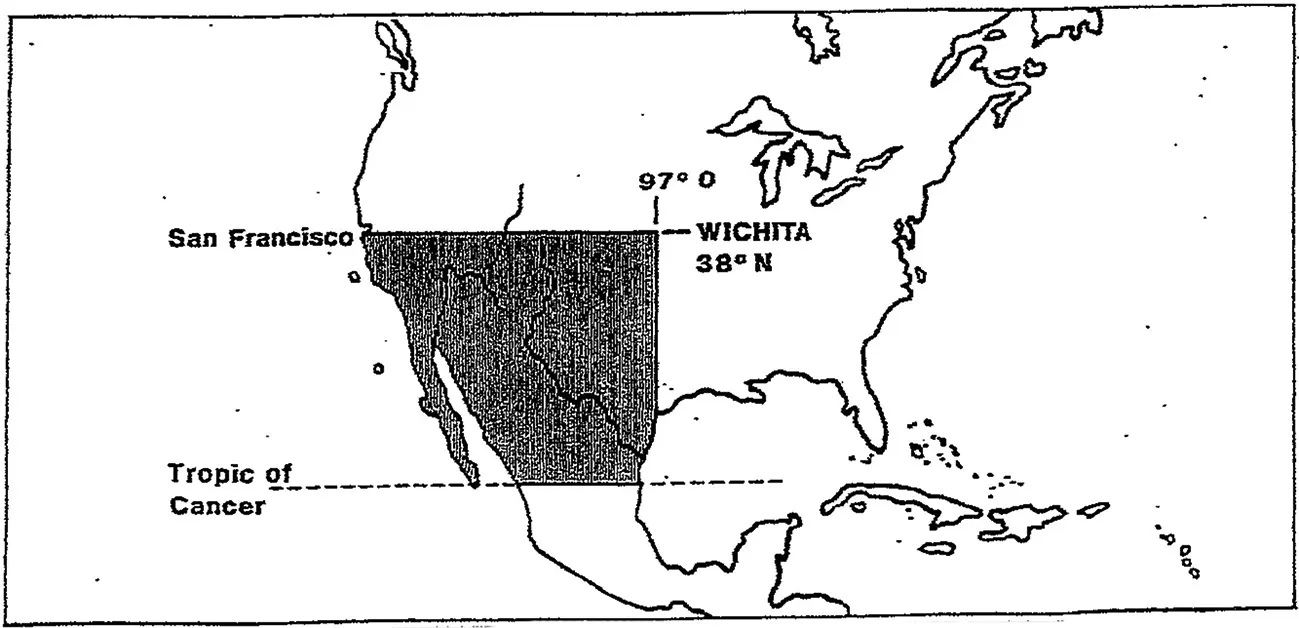

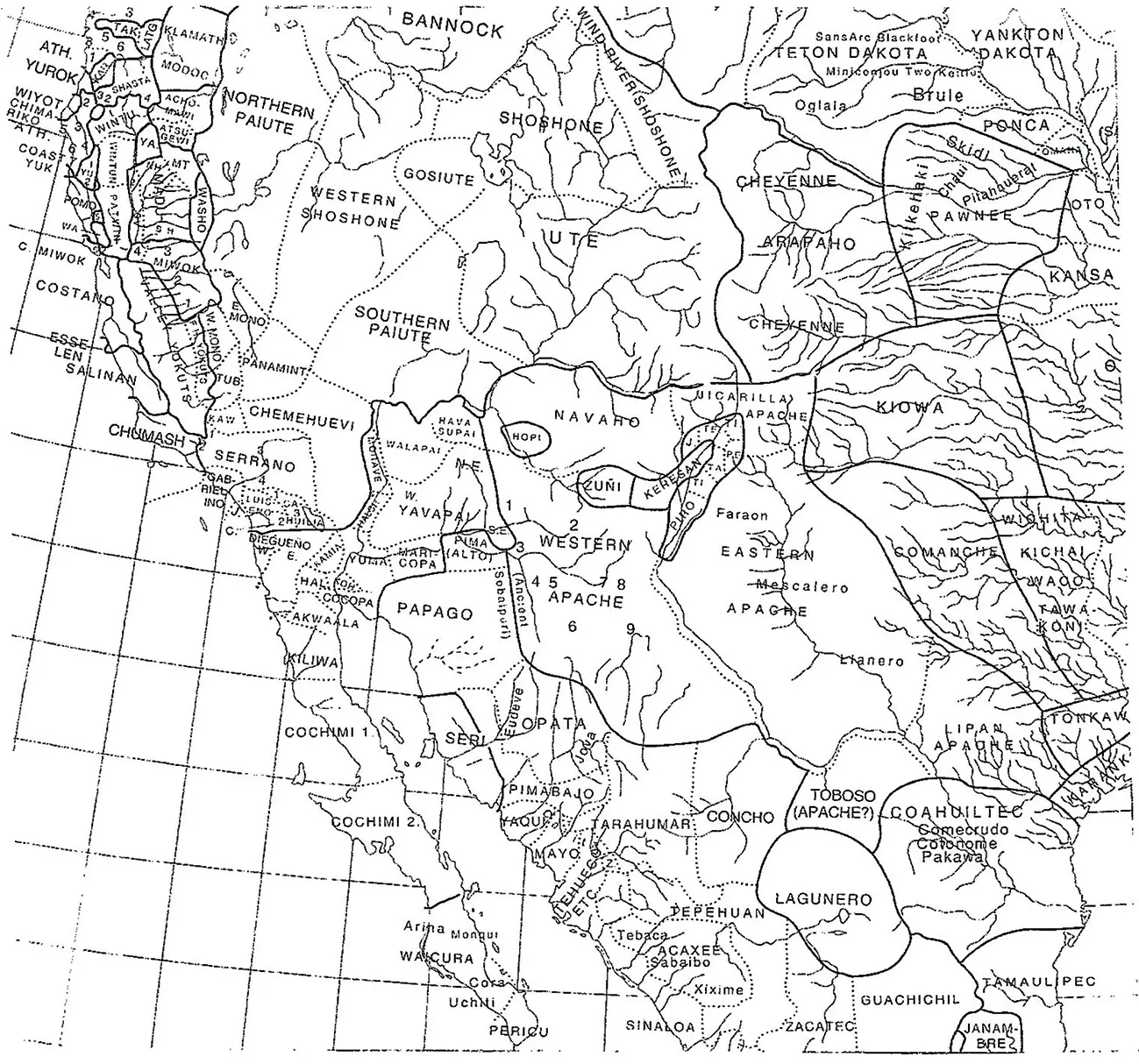

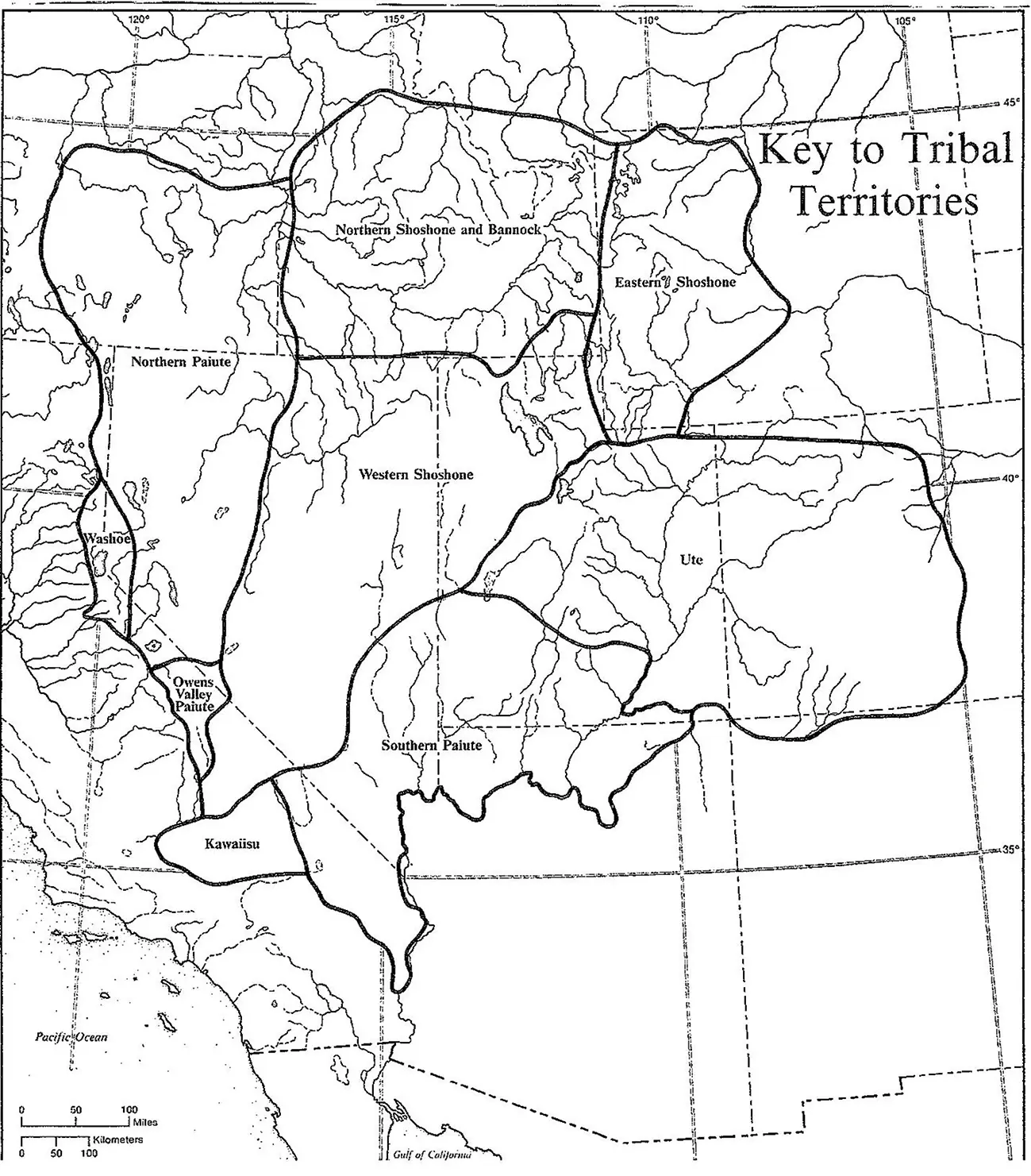

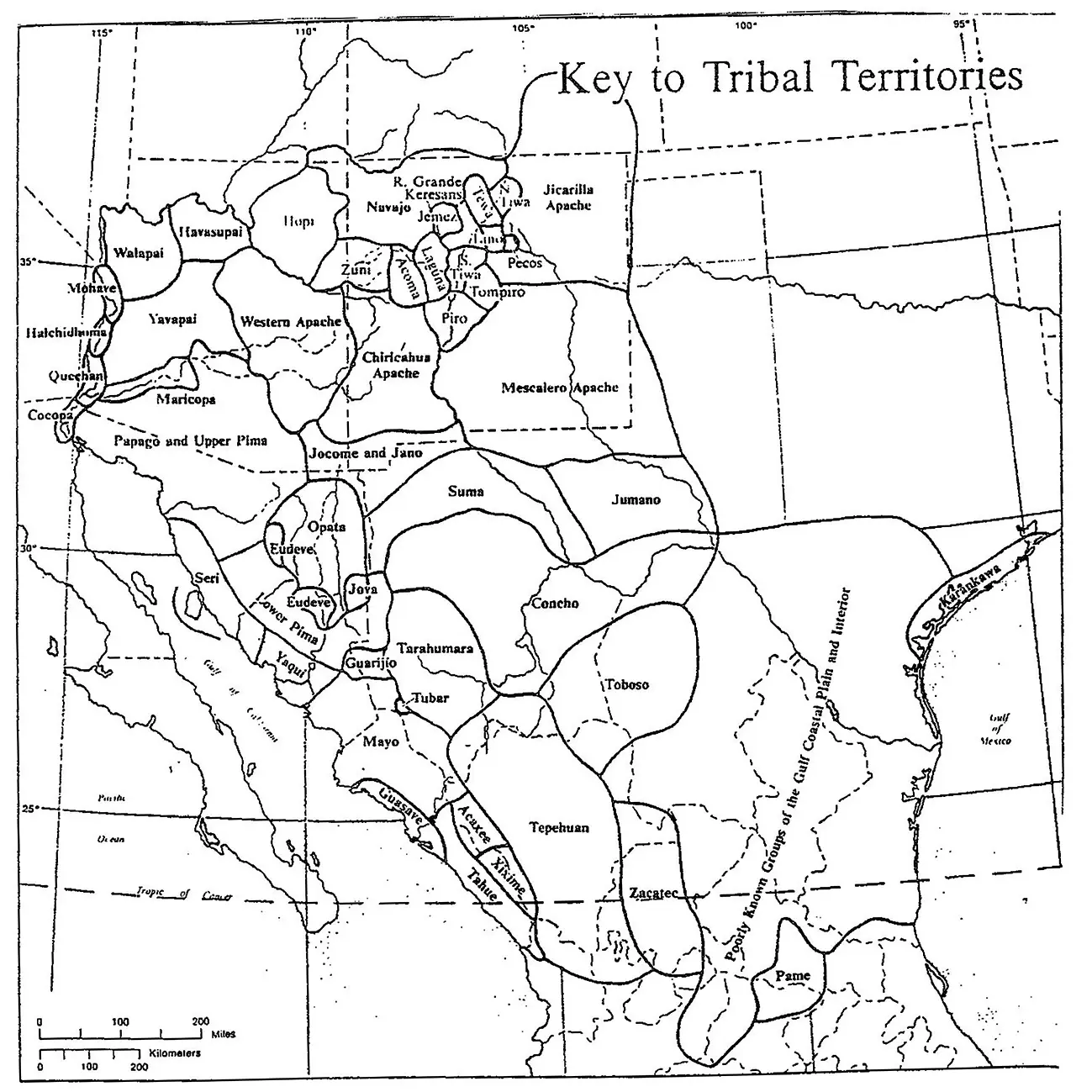

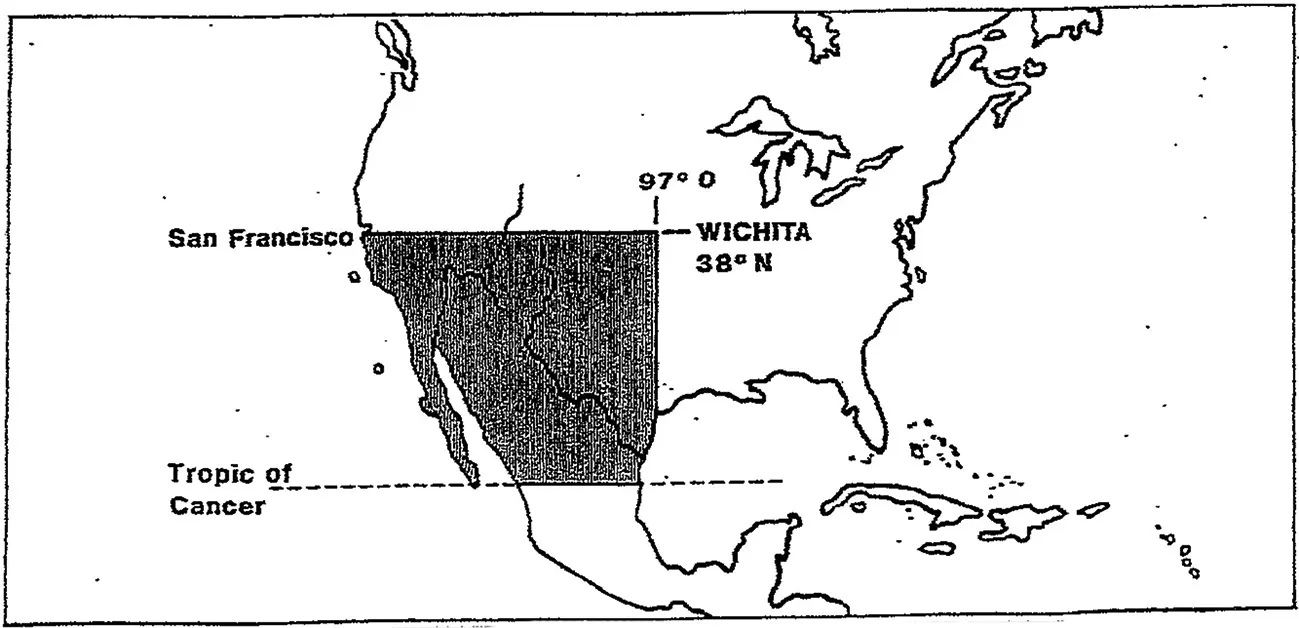

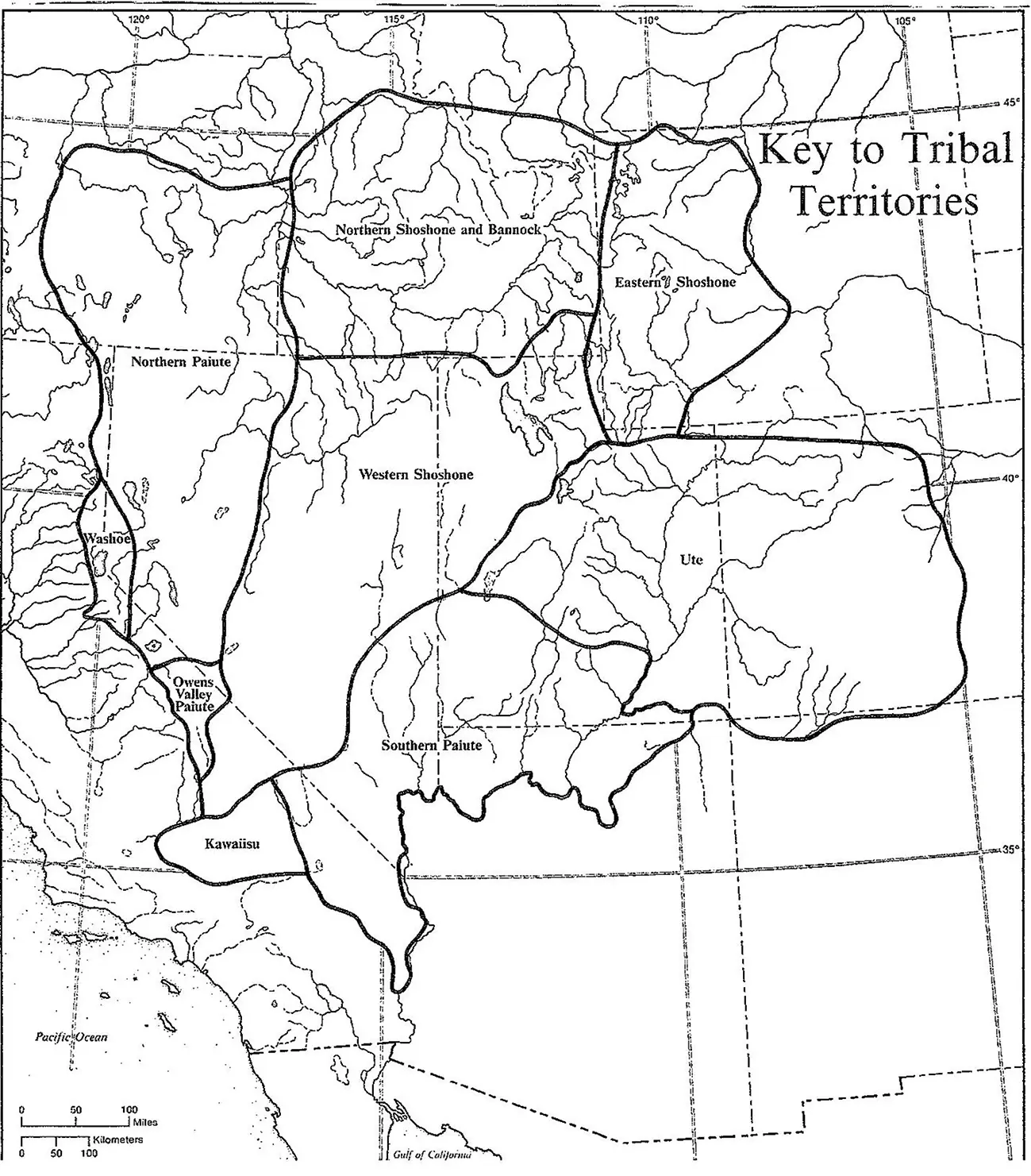

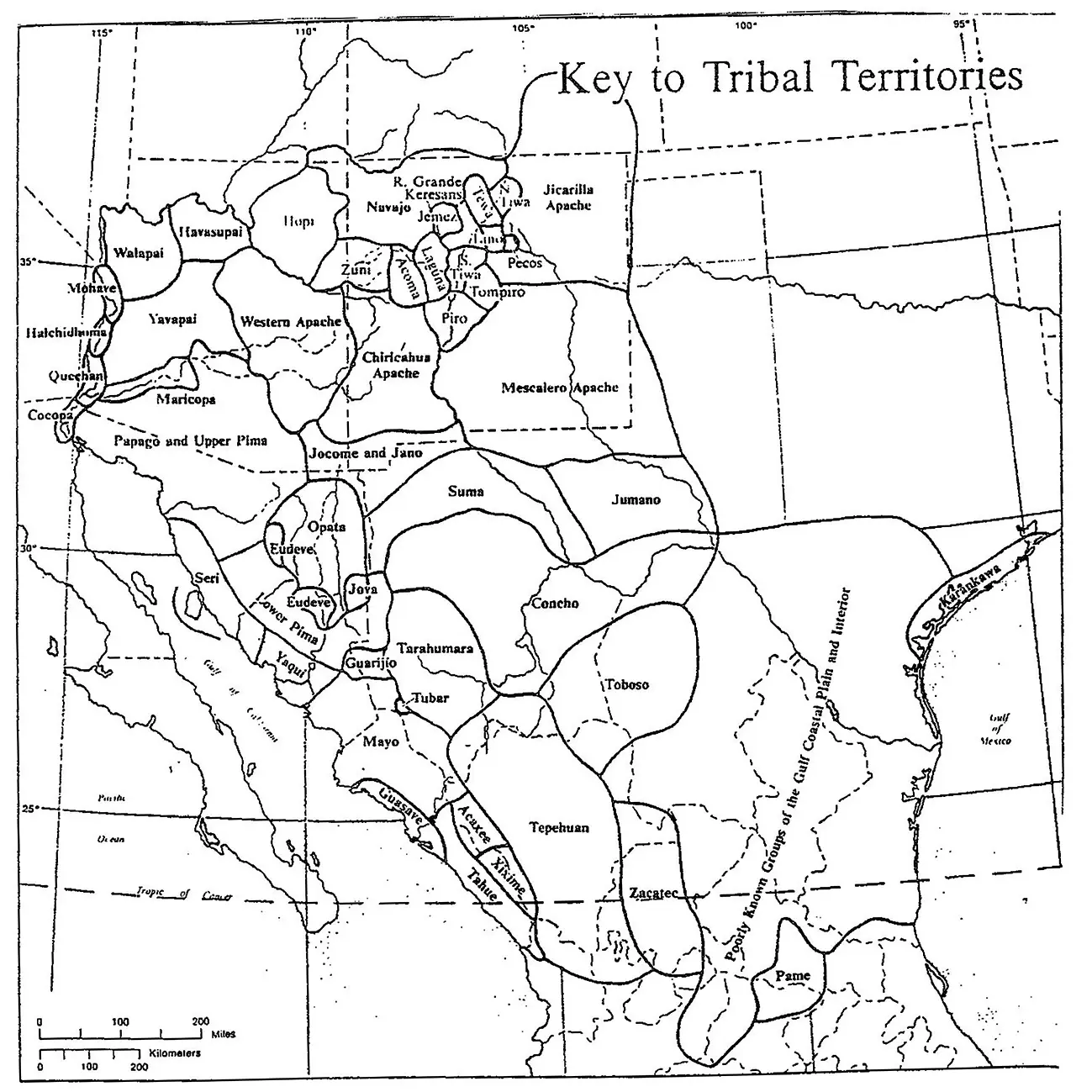

As noted earlier, the geographical area under study is called the Greater Southwest, territory that is often referred to by geographers and ethnohistorians as the Gran Chichimeca . Anthropologist Charles Di Peso defined the Gran Chichimeca as comprehending all of that part of Mexico that is situated north of the Tropic of Cancer to 38 degrees north latitude, including Baja and Alta California, New Mexico, southern Utah, southern Colorado, and western Texas (see map, Figure 0.2). This writer would extend the line north to 42 degrees north latitude or the northern boundaries of California, Nevada, and Utah (including the Great Basin area) with the northern boundary extending from California to 97 degrees west longitude near Wichita, Kansas (see maps, Figures 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5).

Figure 0.2 Charles Di Peso’s La Gran Chichimeca : The Greater Southwest (including Central Rockies and Great Basin).

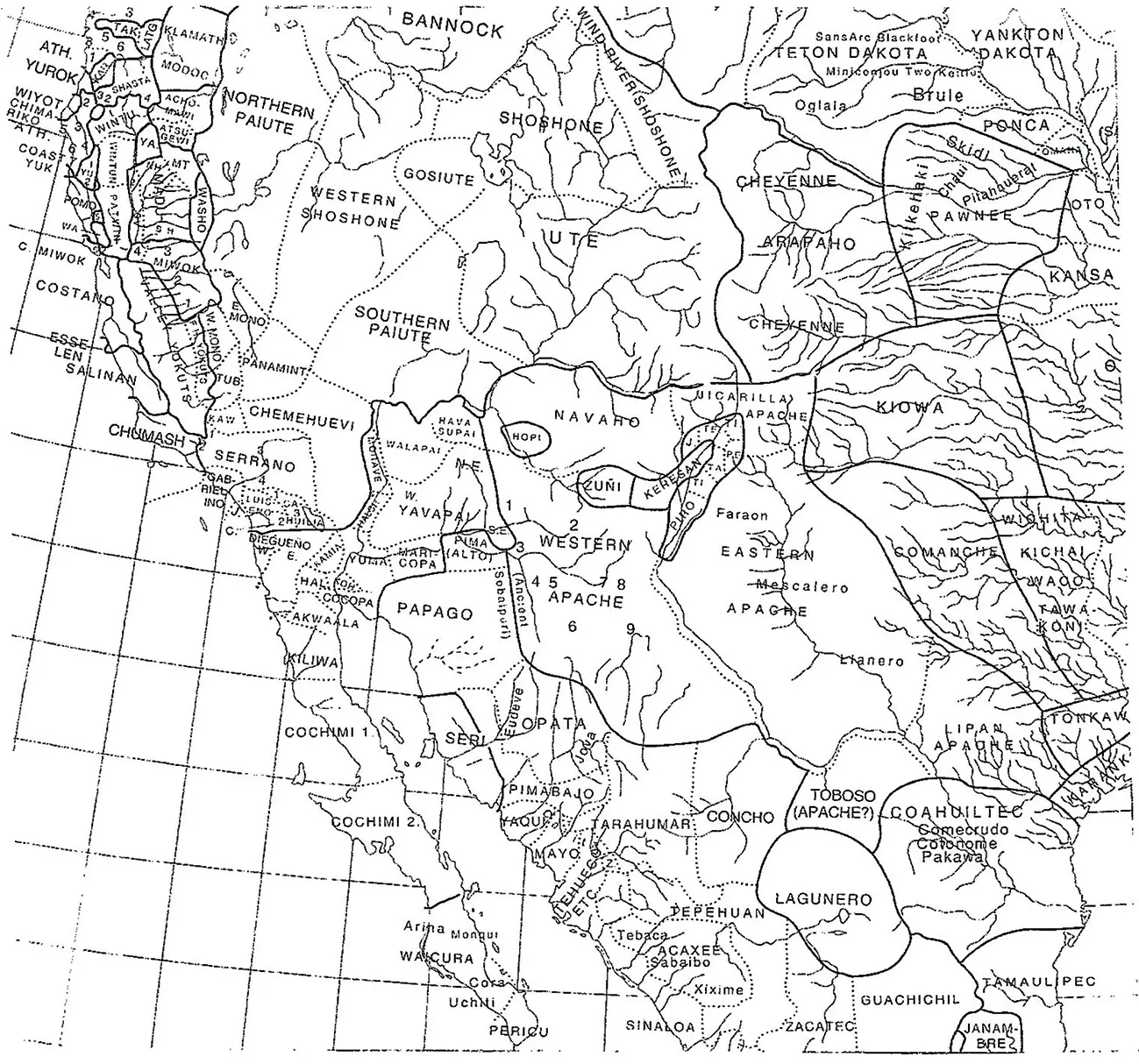

Figure 0.3 Indigenous Communities of the Greater Southwest . Abridged from Map 1-a, Native Tribes of North America , Map Series No. 13 (University of California Press).

Figure 0.4 Tribal Communities of the Northwestern and Central Parts of the Greater Southwest .

Reproduced from “Key to Tribal Territories” in Handbook of North American Indians , vol. 11, Great Basin , ed. by Warren L. D. Azevedo (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1986), p. ix.

Figure 0.5 Tribal Communities of the Southern Part of the Greater Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico, and Northern Mexico) .

Reproduced from “Key to Tribal Territories” in Handbook of North American Indians , vol. 9, Southwest . ed. by Alfonso Ortiz (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1979).

More importantly, this is an ecological and historical zone of cultural interaction. It was here that Mesoamerican societies made commercial contact with the Indian cultures of the US Southwest. For example, in pre-contact time turquoise and buffalo hides came from Chaco Canyon to be exchanged for Macaw feathers and chocolate from Guatemala and Mesoamerica. This was where Anglos first confronted Spaniards in North America. This was the homeland of the Tejano–Mexicano conflict prior to 1845, or the area where Geronimo roamed freely between two nation states after 1850.

For the purposes of this study history does not stop at the border, even though there has been an international boundary since 1848. Not only did Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apaches fight, hunt, and raid in this region (paying no heed to the boundary), but treasure seekers, settlers, surveyors, munitions dealers, US Army Indian scouts, and others constantly travelled back and forth. O’odham traders exchanged goods and slaves between Mexico and the Gila Indians in the north. The Yaqui Indians of Sonora sought refuge in southern Arizona. Mormon pioneers and colonists went out from Zion in the Salt Lake Valley northward to southern Idaho and southward and westward to southern Utah, Nevada, southern California, Arizona, and Chihuahua, Mexico. The history of Gran Chichimeca, named by the Aztecs for their “barbarian” neighbors who lived a nomadic life in the region, is the story of cultural, economic, and social interaction from Mesoamerican times to MexAmerica today.

Finally, it should be noted that the theme of “relocation and removal” must be expanded to include its global and contemporary dimensions. The cultural struggle between westernized and non-westernized people or between colonial and indigenous peoples is both world-wide and on-going. The ideological, spiritual, and economic imperatives of colonial expansion were not exclusively European, and the occupation of indigenous lands took place throughout India, Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Thus it is that immigrants from North India confronted the Veda (forest dwellers) of Sri Lanka; the Japanese government refused to recognize the Ainu who inhabited Hokkaido in the northern archipelago until the 1990s; the Bushmen or desert-based hunter-gatherers of southern Africa face extinction today because of limited resources and outsider populations; and the Yanomami and Uru Eu Wau Wau of the Amazon Basin are confronted with challenges to their traditional way of life from scholars, tourists, loggers, miners and other developers. 11

Читать дальше