By the early 1870s the fighting that characterized Indian–white relations had subsided, and reformers began to argue that the cost in lives and property was not worth the military effort. Grant’s peace policy called for non-violent coercion by Protestant missionaries who would direct affairs on newly established reservations. These agents would both convert their charges to Christianity while teaching them the value of farming and other rural tasks. By accepting the reservation solution the federal government in effect recognized the Indians as wards of the state—the American form of colonialism.

Yet by the late 1870s the failures of reservation life, characterized by bribery and dishonesty by those who were charged with implementing the Indian policy, and by a ration system that was both inadequate and yet fostered dependency on hand-outs by an impoverished Indian people, led to new reform movement. It was in this context that the off-reservation solution was posed by Pratt and others. If overt military actions and segregation on reservations were not transforming the Indian to a civilized person, perhaps education should be tried. Education might finally detribalize Indian youths, convert them to Christianity, and provide them with the gift of the white man’s civilization. 8

Education would not only include as it aims Christianization and citizenship training, but also would incorporate the rudiments of academics such as the ability to read, write, and speak English, as well as facilitate individualization by developing a work ethic that promoted the ideal of self-reliance as well as respect for private property. 9Education would produce assimilation, and this would result in a new American who no longer would speak his or her tribal language, avoid “pagan” thoughts and rituals, and would leave behind any notions of community and communal values. And it should be an educational process that would not be thwarted by angry parents and traditional forces on the reservation.

One solution was to distance the school children from their family and tribe. Not only did the federal officials believe that the children should be separated from their “tribal” and “savage” ways so as to become “civilized,” but by separating them from their families they could be used as hostages to insure proper behavior by their parents back at the reservation. This type of education would be a different kind of relocation policy, a sort of education that would assimilate and integrate the Indian into American society. It would be a form of cultural genocide, or as one writer called it, “education for extinction.” 10And the model for organizing an off-reservation school like Carlisle would be a military one, and Richard Henry Pratt would become its first officer and teacher.

Having served in the military for the Union cause during the Civil War, Pratt, when the war was over, retired from the army to manage a hardware store in Logansport, Indiana. Pratt, finding himself temperamentally ill-suited for the hardware business, joined the regular army in 1867 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Tenth Cavalry, an all-“Negro” unit that had Cherokee scouts attached to it. 11For eight years, from 1867 to 1875, Pratt spent much of his time in what would become Fort Sill in the heart of Comanche and Kiowa country fighting plains Indians. When the Red River War of 1874 was concluded, he was ordered to escort 73 prisoners of war—Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, and Arapahoe—to Fort Leavenworth. On May 11, 1875 he was further ordered to transport the prisoners to the old Spanish fortress of Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. 12

It was at Fort Marion that Pratt became more of a teacher than a jailer. He decided that he would rehabilitate his prisoners and received permission to teach his captives vocational skills that would hopefully lead them to become useful citizens. He cleaned them up and gave them military uniforms to wear. The Indians were instructed on pressing their trousers and shining their boots. He instituted daily inspections in which every Indian would stand at attention at their freshly made beds. They received haircuts. For exercise they would drill in army maneuvers and participate in parade marches. 13

They would also learn to work like white men, especially doing hard labor like stacking lumber or packing crates. Do-gooder matrons from St. Augustine served as volunteer schoolteachers, teaching English and Christian doctrine at the same time. All in all, Fort Marion was turned into a basic training camp that was part school and vocational center, with a catechism curriculum thrown in. The Fort Marion experience was later transferred to the Hampton Institute in Virginia, where 22 prisoners were sent for more schooling. 14The Fort Marion and Hampton Institute experiences convinced Pratt that he had finally found a solution to the “Indian problem,” and his program of eradicating “Indianness” could be permanently installed at Carlisle. In 1879 the secretary of the interior, Carl Schurz, gave Pratt his school. And from Carlisle Pratt’s martial philosophy would diffuse outward to other reservation and off-reservation schools.

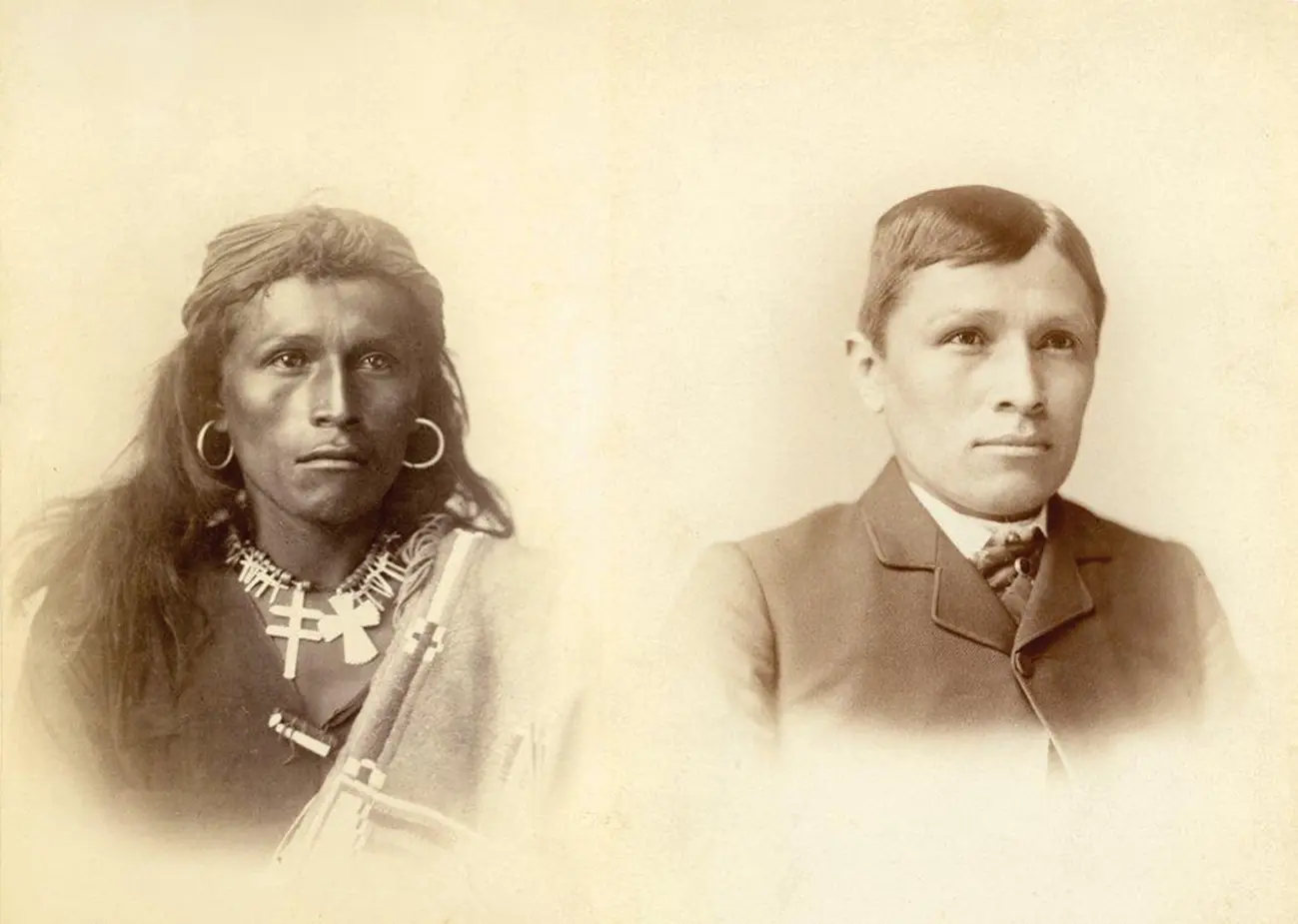

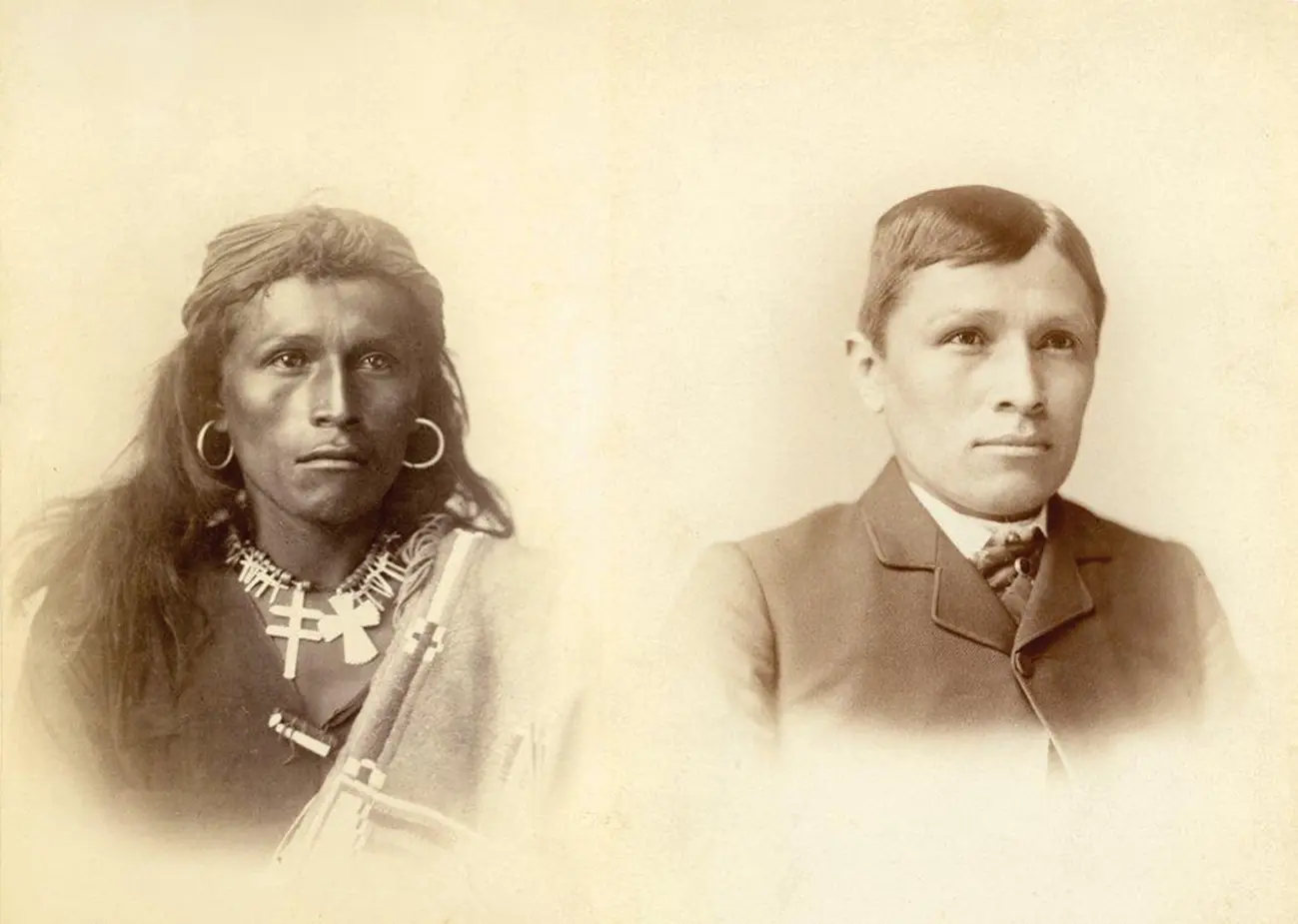

The first concern was one of physical appearance. Holding true to the gender stereotypes of the age, girls were dressed in heavy Victorian-style dresses, while the boys were issued wool military uniforms. Haircuts for the boys would follow; an activity that was especially traumatic for Apache groups.The federal government produced images of the “before and after” of the children to convince the general public of the good work being done to transform the Indian from a savage to a civilized person (see Figure 2.6). Physical bearing, a new haircut, western clothing—all meant a transformation from the brutal state of a savage to that of a civilized, American Christian. The forces of social evolution would be realized by an educational system that would produce proper-looking students who were a boon to local communities (as well as a source of cheap labor). The photo collections were not only a public relations campaign, but a successful marketing device. In selling the “before and after” images to outsiders, the school was selling itself as well. 15

Figure 2.6 Before and After . Tom Torlino (Navajo) arrived at Carlisle Indian School October 21, 1882, at the age of 22 years. After his term was disrupted in 1884, he returned to Carlisle in 1885.

Credit: Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

Part of the transformation included segregating the children by age and gender into companies for marching in close-order drill every morning. Music programs took the form of marching bands that accompanied the students as they drilled and marched in parades. School plays dramatized stories of the saga of Hiawatha or George Washington and the cherry tree in order to instill within them the new American mythology. Native dances were allowed, as long as they were performed on patriotic holidays or celebratory occasions—such as the Fourth of July or Thanksgiving. 16

One poster at Carlisle encouraged male students to participate in sports, seemingly for purposes of exercise but more likely to instill military discipline. The sign urged them to “become a football player or boxer,” and “learn to play a sport and become controlled and civilized.” Appealing to the machismo of teen-agers, the poster instructed them to “develop manly aggressiveness so that you can win a trophy.” Being macho meant that you can “learn to be strong and not to cry or show emotion.” Finally, and this was the clincher, “learn to obey a stern fatherly authority—your coach!” 17

Читать дальше