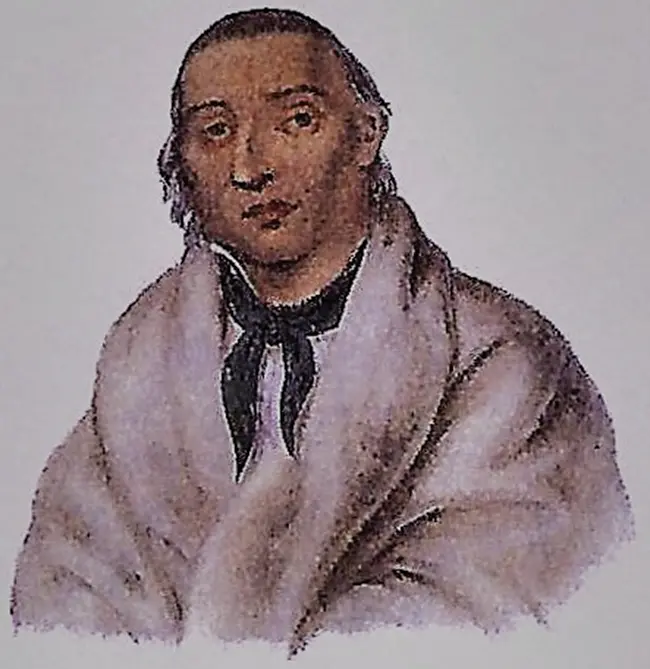

The aftermath of the Minnesota rebellion shaped Lincoln’s Indian policy for the west. First, the western Indians would be treated strictly as a military problem, and the military would be given carte blanche authority to deal with the “wild” Indians of Arizona and Colorado. Secondly, that policy would be one of removal and relocation. In April 1863, 270 Dakota men were moved from Mankato, Minnesota, to a prison camp in Davenport, Iowa, where they were imprisoned for three “gut-wrenching” years. In July of that year the military drove eight to ten thousand Indians out of Minnesota into Dakota Territory, including the scalping and mutilation of insurrectionist leader Little Crow (see Figure 1.1). An 1864 expedition went up the Missouri River as far as Yellowstone with the object of destroying as many Indians as possible. As a concession to the remaining condemned Sioux, instead of execution they would be removed from the state of Minnesota and resettled in the Upper Missouri. 72

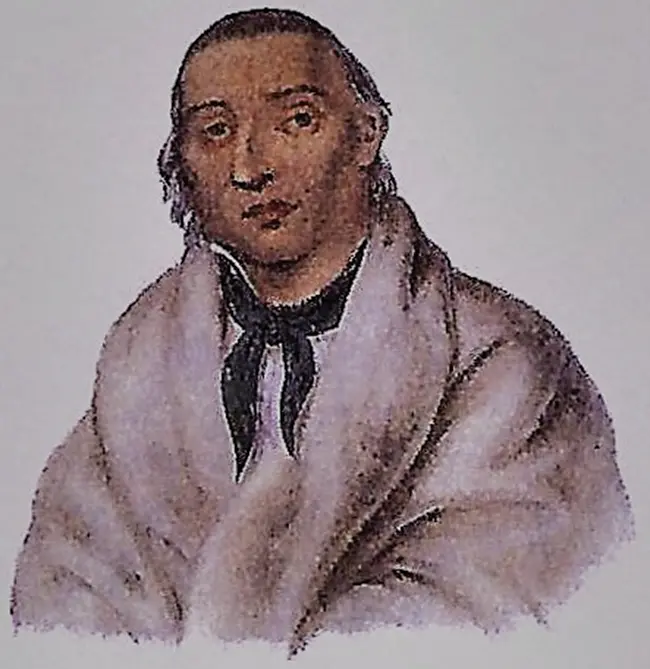

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Sioux Chief, Little Crow (1824) . From Native Americans: An Illustrated History (Atlanta: Turner Publishing, Inc., 1993), p. 327.

And even though most Winnebagos (Ho-Chunk) had not been involved in the 1862 rebellion, they too were forced to relocate to Crow Creek in Dakota Territory. They had to move because the settlers in Minnesota wanted their Winnebago land. Like the Sioux, the removal trip cost many lives, especially of women and children. Once they arrived at Crow Creek they found that they had been forced to trade good land for inferior, sandy soil. Finally, as usual the 1,300 Winnebagos were surrounded by 600 white profiteers and the brutality of military guards. 73

The 1863 removal and relocation of the Mescalero Apaches and Navajos to Bosque Redondo in New Mexico took place in the shadow of the Minnesota uprising, and was the result of Lincoln’s wartime militarization of the Indian problem. As the Sioux reservation was opened up to white settlers, it was closed to the Sioux and they were forgotten. Although Lincoln’s humaneness was shown in his clemencies of several Santee Sioux warriors, it was still the largest mass execution in American history in which the guilt of the accused was in doubt. His Minnesota policy, shaped in part by the realities of politics and the pressures of the Civil War, became the template for Indians elsewhere, with Arizona’s Navajos, Mescalero Apaches from west Texas, and Paiutes south of Lake Tahoe being relocated, and Cheyennes and Arapahos in Colorado being massacred at Sand Creek by the military. The army had proposed a similar removal plan for the California Indians where they would be relocated from the mainland to a concentration camp on Catalina Island. Fortunately, Commissioner Dole halted these preparations. 74Lincoln’s last proclamation was also militaristic in that he ordered the execution of any soldier found guilty of smuggling arms to the Indians. 75

Earlier in 1858, while debating the status of slavery with Stephen Douglas in the famous Lincoln–Douglas debates for the senate in Illinois, Lincoln argued not for the equality but for the freedom of the “Negro.” The words of Douglas more clearly reflected the public sentiment. He contended that he was opposed to “negro” citizenship in any form, saying that “I believe this Government was made on the white basis. I believe it was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever, and I am in favor of confining citizenship to white men, men of European birth and descent, instead of conferring it upon negroes, Indians [italics mine], and other inferior races [audience response—‘Good for you; Douglas forever’].” 76

A more vengeful attitude was expressed by the citizens of Minnesota in a May 6, 1863 article of the Saint Paul Pioneer . The steamboat Northerner was sent to St. Paul to pick up refugee Dakotas, mostly women and children, who were being sent to Crow Creek in Dakota Territory. Before it could take them aboard it needed to unload a hundred or so emancipated slaves who were brought north to act as mule drivers for the army’s spring expedition against Little Crow and the Dakotas still in rebellion. As the newspaper said: “The Northerner brought up a cargo of 125 niggers and 150 mules on Government account. We doubt very much whether we benefit by the exchange. If we had our choice we would send both niggers and Indians to Massachusetts, and keep the mules here.” 77

Lincoln shared the biases of his generation. According to Lincoln the Indians were savages, while the white man was civilized. In spite of the Civil War, Lincoln noted, white men generally shunned war and sought peace, while the “redmen” were disposed to fight and kill one another. Christianity was superior to any Indian religion. They were an inferior, vanishing people who were destined to be pushed aside by white Americans. Like the Minnesota voters who decried slavery in the southern states, he was silent about the degradation and exploitation of America’s Native Americans. Like his protagonist Frémont, he closed his eyes to the plight of the Indian. 78

Yet the memory of Lincoln was that of “the Great Emancipator.” Shortly after Lincoln’s death, Kirby Benedict, a federal judge in the Territory of New Mexico, wrote a eulogy to President Abraham Lincoln. It ended with these words: “The voice of the blood of Abraham Lincoln will never cry in vain to Heaven from the free ground upon which it has been shed.” 79Lincoln was the author of one of the most important documents in the history of the American Republic. His leadership during the Civil War in which he destroyed the institution of Black slavery and preserved the Union at all costs made Lincoln a great statesman. Not only did Lincoln, a grieving father, manage affairs on the domestic front, he also gave to Mexico material and manpower that enabled Benito Juárez and his Republican Army to defeat the imperial armies of France and Austria. In this latter sense Lincoln was not only a great national leader, but was an important international figure as well. 80Yet, and unfortunately, from the point of view of many Indians “the Great White Father” was ultimately just another politician.

Commentary: Lincoln and the Pueblos

Like most presidents, Lincoln had little or no knowledge and experience with the American Indian. On a personal level he considered them inferior to the white man and dealt with them in a paternalistic way. Most of the Indian matters that confronted him in office were handled by other officials in his administration. Lincoln’s Far West policy was to promote the interests of the transcontinental railroad, miners, farmers, and preachers. In other words, Lincoln personified the ideals of “Manifest Destiny,” which held that the Indians were an obstacle to the expansion of western civilization and must be removed to make room for Christianity, mineral extraction, farming, and the railroad. Most of the Lincoln administration activities involved the cession of Indian lands and the removal and relocation of the Indians from their homelands. While he did get involved in the Sioux conflict in Minnesota, and was concerned with the affairs of the pro-Union Cherokee, he took no part in the events in the New Mexico territory involving Navajos and Mescalero Apaches. The Navajo Long Walk was administered solely by military personnel of the New Mexico district.

His paternalism did reveal itself in his treatment of the Pueblo Indians. Perhaps, Lincoln, like many of his compatriots, considered them to be more “civilized” than the average “savage” because the Pueblos lived in a sedentary way, dwelling in apartment compounds and practicing agriculture. Pursuing the model of the Spanish King in 1620 and the example of the Mexican government in 1821, he awarded Pueblo leaders with silver-headed ebony canes engraved with his name:

Читать дальше