1.3.4. Artificial versus natural forms

From an early date, observations of persistence were linked to the idea that manmade forms had a greater capacity to withstand the test of time than natural forms, simply due to the role played by human rationality in their creation. For N. Bergier, ancient roads survived primarily due to the role of human reason:

The form of the great highways is artificial, consisting of an assembly and arrangement of the aforementioned materials in a certain order, invented by human industry through the use of reason: not only to create them, but also to preserve them as long as the craftsmen’s art and the nature of the materials themselves would permit. 33 (Bergier 1622, p. 135)

Bergier’s whole work was devoted to the development of an ideal model of the ancient road, which he presented as a veritable architectural order (Robert and Verdier 2014, pp. 11–71). He created a classification of highway-building materials using a scale of values, from the least useful natural deposits to the most sophisticated man-made materials, such as “Tiles [...] formed not by the hazards of time, but using rule and compass” 34 (Bergier 1622, p. 193).

The same type of opposition resurfaced three centuries later in the work of Lavedan, who suggested that towns could be split into two categories: “spontaneous towns, born of chance and which grew up gradually, and artificial towns, created in a single day by the will of one man” 35 . In the first case, he considered that towns “left to chance, or to nature, the task of grouping the component elements around the generating element” (road, watercourse, relief, etc.), while artificial towns were “constructed following a predetermined plan”. He added that the latter represent “the specific object of study of a history of urban architecture: not always works of beauty, but always works of art, or in other terms, intentional creations of human ingenuity” 36 (Lavedan 1926a, p. 5). Lavedan established a hierarchy of plans based on their independence with respect to the natural dispositions of the host site and on their geometric complexity: from the “inorganic village, in which dwellings seem to have sprung up at random” to “the checkerboard plan, with a grid pattern which is now the boast of many cities of the New World, from Buenos Aires to Chicago” 37 (Lavedan 1926a, p. 31). The artificial form as a work of art, particularly the regular geometric plan, was seen as a product of human rationality forging a structure with the capacity to slow the decay of forms under the influences of time and nature ( section 1.2.5). Thus, while M. Poëte emphasized the role of natural sites and of the location of towns within a network of transport arteries in the context of urban planning, P. Lavedan developed an esthetic vision independent of geographic realities. This approach left an indelible mark on the study of urban morphology, both in architecture and archeology.

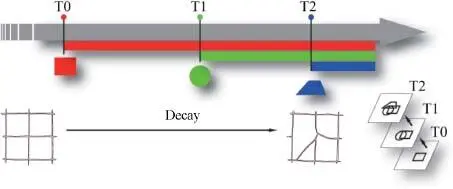

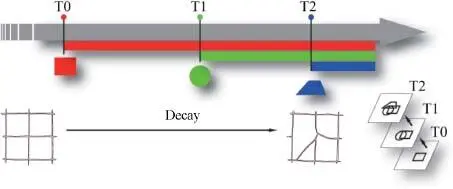

In the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the past was seen as forming an integral part of the present in landscape. Diachrony and the palimpsest metaphor offered two means of understanding the coexistence of different temporalities based on the notion of accumulation. The diachronic vision, however, revolved around the idea of an initial, finished form subject to decay over time ( Figure 1.4). From a scientific perspective, initial states are reconstituted using the regressive method, removing later elements that blur the view. In the absence of a clear logical framework for the evolution of landscape forms, however, this method is difficult to use except in identifying forms which, in theory, have undergone few transformations. Morphologists thus focus on the study of planned forms, which seem the most likely to be well-preserved, due to their independence from the geographical substrate and their structural “hardness” ( dureté ). The culturalist school chose to focus on these forms due to their esthetic properties, and because they appeared most likely to guarantee, or even restore, a certain social order. As we shall see, this notion, with its inherent idea of temporal reversibility, is not far distant from that of engineering resilience: an important element in current debates on the use of resilience ( section 5.2.4).

Figure 1.4. Diachrony in landscape forms. The present landscape is seen as an accumulation over time. The past, complete initial form is visible in the present, but in a decayed state. It can be reconstructed by removing later forms (regressive method). The point of reference forms part of a “resistant” past, to which it is theoretically possible to return (Robert, 2020)

1 1When these cuttings present “grids of equidistant axes, defining square or rectangular units, called centuriae” (see entry “centuriatio” in the Dictionary of Surveying on www.archeogeographie.org, accessed on January 20, 2018).

2 2Author’s note: for citations from works for which no English edition is available, a translation is provided in the text, with the original in the footnotes. In this case: ...du moins mal connu, qui est généralement aussi le plus récent ou le plus proche de nous, comme par exemple le paysage actuel ou le cadastre du XIXe siècle, pour remonter dans le passé à l’aide d’indices de plus en plus difficiles à interpréter à mesure qu’ils sont anciens, mais dont l’enchaînement historique ne fait pas de doute .

3 3Both authors were founding members of the Institut d’urbanisme de l’université de Paris (IUUP), establishing schools of research which were prevalent in typomorphology in both Italy and France in the years following the Second World War (Cohen 1993; Darin 1998).

4 4Un principe, sinon universel et absolu [...], du moins applicable à la majorité des cas : la loi de persistance du plan.

5 5Mass-produced prints popular in France in the late 19th century, many featuring a hidden image concealed within the broader view.

6 6Peuplement: not just “population” in the usual sense of the term, but also “peopling”, i.e. settlement, the way in which man inhabits the land.

7 7Plus encore peut-être que le groupement des maisons ou leur forme, la disposition des champs est le livre où les sociétés rurales ont inscrit, ligne sur ligne, les vicissitudes de leur passé. Malheureusement, ce grand palimpseste des terroirs attend encore sa paléographie. Du moins, de nombreux travaux, au cours de ces dernières années, se sont-ils efforcés d’en déchiffrer quelques pages.

8 8First proposed by the meteorologist Griffith Taylor after 1911, and later introduced in France by Georges Jorré (1899–1956).

9 9... déchiffrer cette écriture sur son palimpseste de sable...

10 10Ce qui est sûr, et c’est en définitive ce que retiendra le morphologue, c’est la survie étonnante de ces lignes privilégiées anciennes par-delà les orogenèses, telles les lettres cachées d’un palimpseste, et surtout leur action tyrannique sur les traits du présent.

11 11...portant en lui la trace de son passé.

12 12Based on lectures given by Saussure, the first edition of the book was published posthumously in 1916.

13 13Author’s note: cf. the English term “durable”, from the same root, which combines elements of “hardness” with a notion of continuity over time.

14 14...la dureté et fermeté de l’ouvrage, qui depuis quiez ou seize cens ans resiste au froissement du charroy.

15 15Quandiu stabit Colyseus – stabit et Roma; quando cadet Colyseus – cadet et Roma; quando cadet Roma– cadet et mundus.

Читать дальше