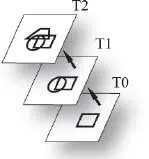

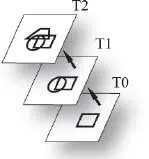

Despite the transformations brought about by industrialization, medieval settlements remain evident on maps, with an accumulation of different forms of habitation on the same ground footprint ( Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Palimpsest as accumulation. The palimpsest came to be used as a metaphor in landscape studies in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, communicating a notion of an accumulation of forms, rather than erasure and replacement (S. Robert 2019)

The palimpsest metaphor has not only been applied to habitat distribution, but also to agrarian structures and to landforms. In 1934, the historian Marc Bloch, using the same notions of reading and deciphering as the English authors cited above, wrote:

Field layout, perhaps to a greater extent than even the grouping or form of houses, is the book in which rural societies inscribed, line by line, the vicissitudes of their past. Alas, a paleography of this great territorial palimpsest has yet to emerge. Nevertheless, several authors, in recent years, have attempted to decipher a few pages 7 . (Bloch 1934, p. 483)

In the early years of the 20th century, geomorphologists used what they called “palimpsest theory” 8 to describe natural cirques which bear the imprint of successive phases of glacier coverage, even after the glaciers in question have retreated (Jorré 1933, p. 365). In 1934, describing the wind direction recorded in the morphology of sand dunes in the Sahara, the geographer Léon Aufrère spoke of “deciphering the writing on this sandy palimpsest 9 “ (Aufrère 1934, p. 130). Jean Demangeot used the palimpsest metaphor in a similar way in relation to the direction of geological folds and the hydrographic network:

That these ancient, favored lines have survived beyond orogeny, like the hidden letters of a palimpsest, is clear; this is the key fact retained by morphologists, notably in terms of the tyrannical action of these lines on present features. (Demangeot 1943, p. 571) 10

The use of the word “tyrannical” implies a negative judgment on the part of the geographer; this critical regard with respect to persistence was a salient feature of discussion in the decades following the Second World War (see Chapter 2). During the first half of the 20th century, however, the palimpsest concept was essentially used to understand observations: the past survives in the present, in the ground footprint of certain forms, orientations, directions, etc., even in cases where the initial reasons for this footprint (populations, land administration systems, winds glaciers, etc.) are long departed.

1.2. Change, an eternal constant?

1.2.1. The diachronic approach

The survival of the past in the present was formalized, in scientific terms, in the area of linguistics in the 19th century. In the specific field of historical etymology, the state of a language at a time t is considered to be derived from a “source” language, and all linguistic phenomena are considered to “carry within them the trace of their past” 11 (Ducrot and Schaeffer 1995, p. 334). Ferdinand de Saussure refined this definition in relation to time in his Course of General Linguistics , introducing the term diachronie (diachrony) (de Saussure 1995a, p. 117) 12 . Formed from the Greek dia , through, and chronos , time, this realm of linguistics describes the successive states of a language and the phenomena which cause a language to shift from one state to another. Above and beyond its methodological implications, diachrony implies a certain vision of time. In Saussure’s view, time is responsible for a dual phenomenon of “mutability and immutability”, in which signs may be altered by time while retaining certain elements:

[…] linguistic changes do not correspond to generations of speakers. There is no vertical structure of layers one above the other like drawers in a piece of furniture; people of all ages intermingle and communicate with one another. (de Saussure 1995b, Part I, Chapter II, § 1)

The state of a language is thus, in part, inherited from the language’s past. The notion of diachrony can be used to take change into account, while retaining links to the past, using the postulate that certain persistent elements establish a type of continuum across and between different periods.

1.2.2. Connecting past and present

In common parlance, continuity denotes “unbroken and consistent existence or operation…a connection or line of development with no sharp breaks” (Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 2008, p. 309). For Saussure, continuity was the first condition for diachrony:

The sign is subject to change because it continues through time. But what predominates in any change is the survival of earlier material. Infidelity to the past is only relative. That is how it comes about that the principle of change is based upon the principle of continuity. (de Saussure 1995b, Part I, Chapter II, §2)

The survival of initial material means that the sign continues to exist over time, but permits alterations in meaning. Language exists because of the “speaking masses”. It is intimately linked to the social mass, which is “naturally inert”, and thus acts as a powerful conservatory factor (de Saussure 1995a, p. 112). The idea of permanence is thus linked to the notion of inertia, one of the fundamental principles of 19th-century mechanics, in which it was used to denote “a property of matter by which it continues in its existing state of rest or uniform motion in a straight line […]” (Concise OED, 2008, p. 727).

Using the notion of continuity, time is seen as duration – durée – that is, as something which runs between two defined limits. The French verb durer , to last, also implies continuation with the same qualities (Larousse 1922, p. 695). A form of analogy seems to have appeared between the terms dur , dureté (hard, hardness) and durée , duration, from an early date; after all, the words share the same Latin root 13 . The Latin verb durare , initially meaning “to harden, to fortify”, also took on a temporal sense in ancient times. Lucretius used the word to suggest that the body could not survive for longer than the soul after death. Tacitus used it to report facts that he had been unable to verify personally, but which had been established by authors who themselves were still alive at the time of the historian’s youth (Gaffiot 1981, pp. 565–566).

The idea that the permanence of forms is a result of resistance, primarily in the sense of material continuity, is an old one. In 1622, for example, N. Bergier ascribed the continued existence of Roman roads to their construction. Speaking of “Brunehaut” roads, wide Roman thoroughfares found across the former Belgian Gaul, he stated that one hypothesis for the use of the term via ferrata (lit. “iron road”) in this context is “the hardness and firmness of their construction, which has resisted wear from carts for fifteen or sixteen hundred years” 14 (Bergier 1622, p. 93). In the 19th century, the historian Camille Jullian also emphasized the hard-wearing ( résistant ) nature of the materials used in ancient road construction, comparing their foundations to an “invisible wall” (Jullian 1964, pp. 108–109). The continued existence of ancient roads was thus considered to be intimately linked to the notion of physical resistance. The dureté , hardness, of their construction ensured their durée , perennity, long after Rome had fallen. Material hardness may also be linked to the durability of power. In a proverb quoted by the Venerable Bede in the 7th century, the persistence of Rome, and, by extension, of the whole world, is linked to the resistance of a monument (the Colosseum):

Читать дальше