BIBLIOTECA JAVIER COY D’ESTUDIS NORD-AMERICANS

https://puv.uv.es/biblioteca-javier-coy-destudis-nord-americans.html

DIRECTORA

Carme Manuel

(Universitat de València)

The Refugee: Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada

By Benjamin Drew

© Vicent Cucarella Ramon, ed.

1ª edición de 2021

Reservados todos los derechos

Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial

ISBN: 978-84-9134-911-2 (papel)

ISBN: 978-84-9134-912-9 (ePub)

ISBN: 978-84-9134-913-6 (PDF)

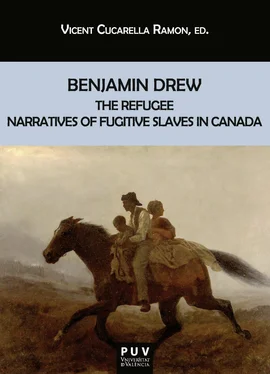

Imagen de la cubierta: A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves , Eastman Johnson, ca. 1862. Óleo sobre cartón, 55.8 x 66.4 cm. Brooklyn Museum.

Donación de Gwendolyn O. L. Conkling, 40.59a-b

Diseño de la cubierta: Celso Hernández de la Figuera

Publicacions de la Universitat de València

https://puv.uv.es

publicacions@uv.es

Edición digital

A ma mare i a mon pare, que saben el preu de la llibertat

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Vicent Cucarella Ramon

A NORTH-SIDE VIEW OF SLAVERY

THE REFUGEE: OR THE NARRATIVES OF FUGITIVE SLAVES IN CANADA

RELATED BY THEMSELVES, WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE HISTORY AND CONDITION OF THE COLORED POPULATION OF UPPER CANADA

INTRODUCTION

ST. CATHARINES

James Adams

William Johnson

Harriet Tubman

Mrs.––

Rev. Alexander Hemsley

John Seward

James Seward

Mrs. James Seward

Mr. Bohm

James M. Williams

John Atkinson

Mrs. Ellis

Dan Josiah Lockhart

Mrs. Nancy Howard

George Johnson

Isaac Williams

Christopher Nichols

Henry Banks

John W. Lindsey

Henry Atkinson

William Grose

David West

Henry Jackson

TORONTO

Charles H. Green

James W. Sumler

Patrick Snead

Charles Peyton Lucas

Benedict Duncan

William Howard

Robert Belt

Elijah Jenkins

John A. Hunter

Sam Davis

HAMILTON

Rev. R. S. W. Sorrick

Edward Patterson

Williamson Pease

Henry Williamson

GALT

William Thompson

Henry Gowens

Mrs. Henry Gowens

LONDON

Aby B. Jones

Alfred T. Jones

Nelson Moss

Francis Henderson

Mrs. Francis Henderson

John Holmes

Mrs.–Brown

John D. Moore

Christopher Hamilton

Mrs. Christopher Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

Mrs. Sarah Jackson

Henry Morehead

An Old Woman

John Warren

Benjamin Miller

QUEEN’S BUSH

William Jackson

Thomas L. Wood Knox

Sophia Pooley

John Francis

John Little

Mrs. John Little

CHATHAM

J. C. Brown

Philip Younger

Gilbert Dickey

William J. Anderson

Henry Crawhion

Mary Younger

Edward Hicks

Henry Blue

Aaron Siddles

John C–n

Reuben Saunders

Thomas Hedgebeth

William Brown

Mr. -

Isaac Griffen

William Street

BUXTON

Isaac Riley

Mrs. Isaac Riley

Harry Thomas

R. Van Branken

Henry Johnson

DRESDEN; DAWN

British American Institute

William H. Bradley

William Hall

WINDSOR

Refugees’ Home

Thomas Jones

William S. Edwards

Mrs. Colman Freeman

Ben Blackburn

William L. Humbert

David Cooper

John Martin

Daniel Hall

Lydia Adams

J. F. White

Leonard Harrod

SANDWICH

George Williams

Henry Brant

Mrs. Henry Brant

AMHERSTBURG

Charles Brown

James Smith

Rev. William Troy

William Lyons

Joseph Sanford

John Hatfield

COLCHESTER

Robert Nelson

David Grier

Ephraim Waterford

Eli Artis

Ephraim Casey

Rev. William Ruth

GOSFIELD

John Chapman

Thomas Johnson

Eli Johnson

Introduction

Slavery was an indelible part of everyday life in Colonial Canada under both the French and British regimes, and the presence of Black people in the country was manifested in literary terms almost from its inception. Long gone is the time in which Canadian studies grounded the beginning of Black Canadian writing with Austin Clarke’s first novel published in 1964. As far back as in 1991, in his now classic two-volume study of Black Canadian literature titled Fire on the Water: An Anthology of Black Nova Scotia Writing , George Elliott Clarke set out to map the origins of Black writing in Canada and stated the seventeenth century as the starting point to consider the beginning of the African experience in the country. In the same vein, Winfried Siemerling’s recent and groundbreaking book The Black Atlantic Reconsidered: Black Canadian Writing, Cultural History and the Presence of the Past (2015) has insisted on the endeavor of tracing back the origins of African Canadian literature 1and explains that “Black writing in what is now Canada is over two centuries old and that black recorded speech is even older” (3). Much earlier than the publication of these two works, the second half of the twentieth century witnessed the revision of the critical history of North American slavery and its unambiguous practices in Canada. Ashraf Rushdie studied this phenomenon and concluded that “the 1960s saw the formation of a contemporary discourse of slavery”, one that “developed new methodologies and generated new visions” (5). Following this trend, two foundational books opened the way to study Canada’s history of slavery: Marcel Trudel’s L’Esclavage au Canada français (1960), later on translated into English by George Tombs in 2013 with the title of Canada’s Forgotten Slaves , and James Walker’s The Black Loyalists (1976). These studies represented new directions in the analysis of slavery and did away with the image of Canada’s acknowledged reproval of American chattel slavery. They also underlined the historical fact that “Canadian history is also black history (and that black Atlantic history is also Canadian)” (Siemerling 8). Truthfully, African slavery in the territory nowadays known as Canada began in New France where slavery was suffered by Black and Indigenous people. The first known evidence of a Black enslaved subject can be found in 1628, nine years after a Dutch ship brought the first cargo of Africans to Jamestown. It was then recorded how David Kirke, otherwise known as the British Conqueror of Québec, took with a slave boy to the French territory, thus installing African people in New France and in British North America thereafter. The petite nègre was brought to New France from Madagascar which proves that slavery not only existed but was well established in Canada.

Indeed, slavery soon became a common and extended practice in New France, and, out of its wealth and influence, the Church became the largest slave owner. When the first farmers and land gentry arrived in New France and were faced with the task of clearing the wilderness and building their farms in these hostile territories, they resorted to the easiest and most controllable labor at hand and thus demanded slaves, despite the fact that this practice was only legalized around 1689 by an edict of Louis XIV, and later on validated in New France in 1709. In sum, as Marcel Trudel reported, there were more than 4.000 slaves between 1628 and 1834, of which approximately 1.400 were Blacks who, in truth, were the favorites of English settlers and were owned by a significant amount of 1.400 masters. Yet, Canadians with, the aid of British policies, have historically considered slavery through the lens of the Underground Railroad, the clandestine network of surrogate homes by which Quakers, black freedmen and abolitionists smuggled runaway slaves towards the North in search of freedom. This episode of North American history has clouded other sides of the reality simply to turn a blind eye to the fact that there also existed slaves owned, exploited, bought, and sold by Canadians themselves. Trudel’s aforesaid work demonstrated that “men and women at every level of French and English Canadian society owned slaves, from farmers, bakers, printers, merchants, seigneurs, baronesses, judges and government officials to priests, nuns, and bishops” (7). This means that slavery in Canada was widely practiced and got eventually spread, to the extent that slaves “were not only an accepted feature of society but were also acknowledged both in law and by notarized contract” (Trudel 8).

Читать дальше

![Benjamin Franklin - Memoirs of Benjamin Franklin; Written by Himself. [Vol. 2 of 2]](/books/747975/benjamin-franklin-memoirs-of-benjamin-franklin-wr-thumb.webp)

![Benjamin Franklin - Memoirs of Benjamin Franklin; Written by Himself. [Vol. 1 of 2]](/books/748053/benjamin-franklin-memoirs-of-benjamin-franklin-wr-thumb.webp)