embodies major themes of the fiction – especially its views of politics, history, society or, more generally, of “reality” – in descriptions, objects, metaphors, artist figures, or scenes based upon the historical visual arts or in the same aspects of fiction conceived and experienced pictorially. (19)

Ideological use suggests that common motives and the symbolic value of historical visual arts recur in fiction; hence, the transferral of political, historical and socio-cultural themes of the visual arts into a literary narrative produces a more intense relationship between the verbal and the visual. The final element of the continuum is interpretive use, which is divided into two sub-categories: perceptual or psychological use, which “refers to the ways in which characters experience art objects or pictorial objects and scenes in a way that provokes their conscious or unconscious minds” (22, emphasis in original); and hermeneutic use, which alludes to the ways in which “references to the visual arts or objects and scenes experienced pictorially stimulate the interpretative process of the reader’s mind and cause him to arrive at an understanding of the novel’s methods and meanings” (23, emphasis in original). Thus, the interpretive use emphasises perception and interpretation of an artwork by both the characters of the novel and the reader.

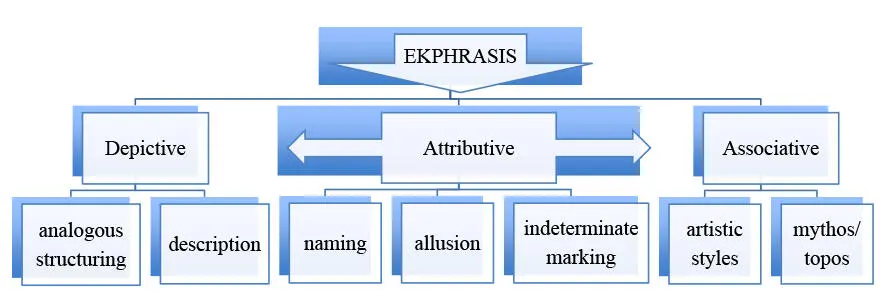

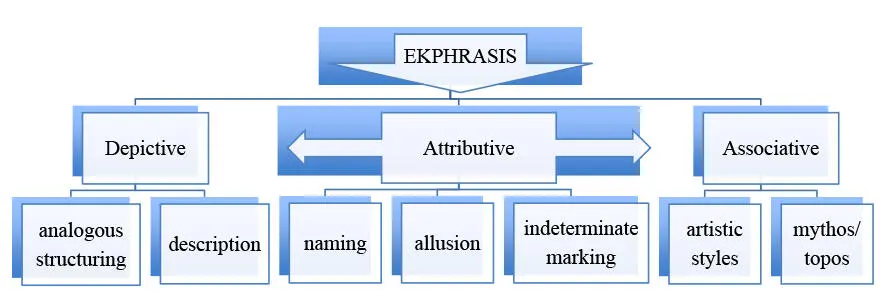

For the present purpose Torgovnick’s continuum is of special interest as it spotlights comparative analysis of two media in prose narratives with reference to historical artists, art movements and actually existing works of art. Similar to Torgovnick’s continuum, Robillard develops two frameworks of intermedial interaction that are based on degrees of involvement of the verbal and the visual, predominantly in poetry. The first model is called the “Scalar Model”, consisting of such categories as communicativity, referentiality, structurality, selectivity, dialogicity and autoreflexivity (56).5 The communicativity category refers to “the degree to which the artwork is marked in a text” (57), ranging “from vague allusions, to a direct reference in a title, to explicit marking in the body of the text” (57). Referentiality refers to “the extent to which a poet actually uses an artwork in the text” (58, emphasis in original). According to Robillard, a text will not reach a high degree in referentiality if the only reference to an artwork is “some form of basic communicative marking” (58). By structurality Robillard means the poet’s “attempt to produce a structure analogue to a picture” (58). The category of selectivity refers both to “the density of pictorial elements which have been selected, either from one painting/sculpture or from several works by the same artist” (59) and to “the transposition of certain topics, myths, or norms and conventions of particular periods or styles of pictorial representation” (59). Dialogicity addresses “the manner in which the poet creates a ‘semantic’ tension between the poem and the artwork by casting the latter in a new, opposing framework” (59). Finally, autoreflexivity is the extent to which the author “specifically reflects on and problematizes the connection between […] his own medium and that of the plastic arts” (59). Robillard herself sees the main criticism of the Scalar Model in the fact that although it provides an overview of intermedial interaction, it does not explain quantitative and qualitative gradation of ekphrastic texts or “the extent to which particular texts are ekphrastic” (60). Robillard thus develops the second “Differential Model”, which aims to make a distinction between degrees of ekphrasis (56). Within the Differential Model there are three categories – depictive, attributive and associative (61) – and each of them has further sub-categories that Robillard illustrates schematically, as shown in Table 2:

Table 2.

Table 2.

The Differential Model (Robillard 61)

This typology moves horizontally and indicates a decreasing degree of ekphrastic relationships not only in the main categories but also in their sub-categories. The first category is depictive. It encompasses texts that explicitly portray a visual source, either through analogous structuring or description . The sub-category of analogous structuring is found furthest to the left in Robillard’s typology because it presupposes “a high degree of structural similarity to the artwork” (61); description is located more to the right since an ekphrastic text “may focus on small as well as large sections of an artwork” (61). Texts that fall under the central attributive category indicate their pictorial source either by “direct naming in the title or elsewhere in the text […]; by alluding to painter, style or genre […] or through indeterminate marking ” (61, emphasis in original). This category has two functions (indicated by arrows). One of the functions is ensuring that texts that aspire to be ekphrastic indicate their pictorial sources; hence, this function is linked to the depictive category. The other indicates the importance of intertextual relationships. For example, when a text refers to a painting but does not otherwise use it “in any other perceivable way” (62) or pay “attention to any of the picture’s structural aspects” (62), it possesses associative elements and is therefore linked to the associative category, which includes texts that refer to “conventions or ideas associated with the plastic arts, whether they be structural, thematic, or theoretical” (62). The Differential Model helps to identify and determine the quantitative and qualitative differences between ekphrases and is applicable not only to the analysis of ekphrastic texts that depict works of art “as vividly as if they were viewed in situ ” (62), but also of those that indicate just a slight presence of a visual source.

Adapting Robillard’s Differential Model to prose narratives and their screen adaptations, Sager Eidt suggests four categories of ekphrasis: attributive, depictive, interpretive and dramatic. Attributive ekphrasis refers to “the verbal allusion to pictures in description or dialog of a text […] in which artworks are […] mentioned, but not extensively discussed or described” (46). Sager Eidt argues that passages in which the pictorial source is mentioned are both quantitatively significant since an artwork receives attention not only as a whole but also via its relation to other objects or characters (46), and also qualitatively significant, as they add to “the signification of the text […], or to the characterization of the protagonists” (46). Although this type of text contains neither a description nor a narrative of an image, it quotes an artwork, and by implication makes reference to its creator. Such references serve as indicators of an intermedial artefact to the reader, who, relying on memory or imagination, may already at this point start re-creating the artwork in question. In contrast, in depictive ekphrasis images “are discussed, described, or reflected on more extensively in the text or scene, and several details or aspects of images are named” (47). Compared to Robillard, Sager Eidt’s descriptive category narrows down the use of ekphrasis to a descriptive function that is integrally related to the ekphrastic re-presentation of a pictorial source. Thus, the depictive category includes ekphrastic texts containing a traditional break in the narrative for descriptions of small or large sections of works of art. Interpretive ekphrasis provides interpretive “verbal reflections on the image” (50). Sager Eidt points out that just as in depictive ekphrasis, “several details of the picture can be mentioned, but […] the degree of transformation and additional meaning is higher” (50). Interpretive ekphrasis introduces not only the interpretation and verbalisation of the painting itself but also reflections that “go beyond its depicted theme” (51). As such, the intensity of meaning production and its transformation make the depictive and interpretive categories qualitatively different. Finally, in dramatic ekphrasis the images are “dramatized and theatricalized to the extent that they take on a life of their own” ( 56). Having the highest degree of enargeia , this category is the most visual of all four. According to Sager Eidt:

Читать дальше

Table 2.

Table 2.