1 Inflation has attacked the foundation of our economy. Inflation has pinned us to the wall.

In example (4), a non-human entity, inflation , is conceived or conceptualized as human owing to the metaphor INFLATION IS A HUMAN BEING (Lakoff & Johnson 1980: 28ff.).2 This metaphoric extension only selects one feature of the source-entity, specifically ‘a human being can be an adversary’, according to the personification INFLATION IS AN ADVERSARY. Categories of entities, including human beings, show a number of properties that can be either viewed as a whole or observed one by one. Categories of entities seem to be organized as so-called Gestalten , that is, structures in terms of which our perception of the world is given a shape, and that exhibit a number of properties, including that of being “at once holistic and analyzable” (Lakoff 1977: 246). Thus, metaphors can also be based on a single property possessed by a category of entities, as in (4).

2.1.3. The conceptualization of the spatial event

Given that spatial concepts are cognitively basic for human beings (cf. Section 2.1.1), it is worth discussing how they are conceptualized. Spatial phenomena can be viewed from different standpoints, and consequently conceptualized in different ways. One of the most important varying parameters, in terms of conceptualization, is “prominence” (in Langacker’s 1987, 2008 terms). Prominence is a kind of asymmetry related to the focus of attention, that is, to what a linguistic expression describes as foreground or background (Langacker 2008: 68). A discussion of different types of prominence follows.

2.1.3.1. The first type of prominence: the profile-base asymmetry

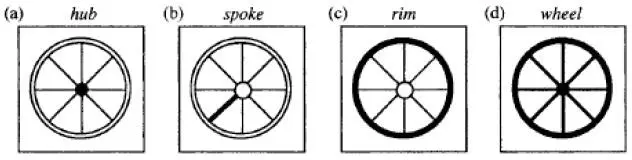

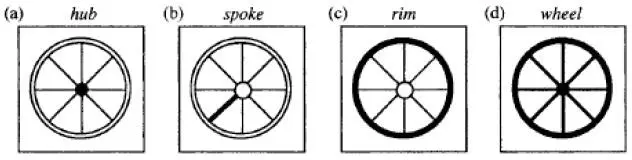

The concept of profile is introduced by Langacker (1987) by means of the word spoke. In order to understand the meaning of spoke, Langacker writes, one must also be aware of what a wheel is. The segment spoke is defined in relation with the structure of the whole wheel . Langacker describes the relation holding between the spoke and the wheel as the relation of a “profile” of a concept with respect to its “base”. The profile is the precise and narrow concept expressed by a word, whereas the base can be defined as the encyclopedic knowledge or conceptual structure presupposed by the said word.1

As Croft (1993) points out, the profile and the base comprise an inseparable pair: a profile needs a base against which it is individuated. Symmetrically, a base cannot be individuated without the profiles that are defined with respect to it. The verb “to profile” corresponds to the noun “profile”. Thus, both these formulations are possible: spoke functions as a profile of the base wheel , or spoke profiles a certain part of the base wheel . In a similar way, the meaning of wheel is also the base for hub and rim , as shown in Figure 1 below:

Fig. 1: The profile-base asymmetry: wheel vs. spoke , rim , wheel (from Langacker 2008: 67)

An expression can profile either a thing, as in Figure 1, or a relationship. Therefore, the concept of profile can also be employed to describe spatial and non-spatial relations and thus the meaning of preverbs. For example, the Homeric motion verb eis-ana-baínō ‘go up to’ profiles the movement of an entity going along a trajectory in a certain direction. This verb contains two preverbs: the former, eis- ‘to’, profiles the direction of motion (Goal); the latter, ana- ‘up’, instead profiles its orientation and Path, specifying that the verb indicates an upward motion. The whole spatial relation expressed by the compound eis-ana-baínō implies that there are a path, an entity that moves along that path, and an entity to be reached, which constitute the basis of the spatial relation.

2.1.3.2. The second type of prominence: the Trajector-Landmark asymmetry

As anticipated in discussing the meaning of the verb eis-ana-baínō ‘go up to’, entities are usually located with respect to other entities functioning as reference points (Talmy 1983; Langacker 1987). This way of locating entities implies a further asymmetrical relation holding between the located entity and the reference-entity.

Talmy (1983) introduces the terms “Figure” and “Ground”, borrowed from Gestalt psychology (Köhler 1929; Koffka 1935), to describe this asymmetrical relation: the Figure is the object to be located, while the Ground is the object with respect to which the Figure is located. In reference works, other terms are also used to identify the participants in a spatial relation, including the pairs “locans”-“locatum” and “referent”-“relatum” (e.g. Rappaport & Levin 1985; Levinson 1996). In this work, I opt for Langacker’s (1987, 2008) terminology, which describes Talmy’s Figure and Ground in terms of focus of attention. Langacker argues that, while profiling a spatial relation holding between two entities, one of such entities is always more focused than the other one. Langacker calls the more prominent and located entity the Trajector (henceforth TR), and the less prominent reference-entity Landmark (henceforth LM).

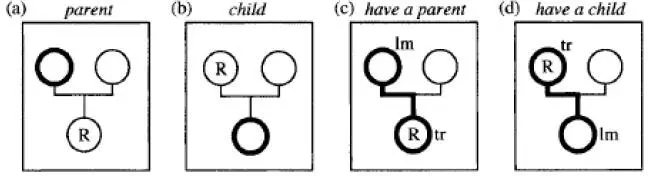

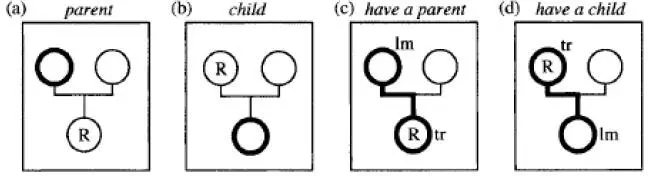

Langacker employs the concepts of TR and LM beyond the cognitive domain of space. Following his lead, let us take as an example the kinship relations of having a child and having a parent . Both relations share the base, that is, the domain of KINSHIP RELATIONS. In addition, they profile the same kinship relation, as they involve two participants, of whom one is the child or the parent of the other. What changes is the directionality of the relation, and thus their TR-LM alignment: having a child is primarily concerned with parents, who thus function as a TR. By contrast, having a parent is a predication concerning the child, who in turn functions as a TR. Figure 2 shows both the profile-base and TR-LM asymmetries:

Fig. 2: Kinship relations: profile-base and TR-LM asymmetries (Langacker 2008: 68)

In Figure 2 (a)–(d), bold highlights the profile. Both in (a) and in (b), the profile is a human entity, either the parent or the child . They are both characterized by the relative role that they play in the kinship relation, which is conceptualized as the base. However, in both (c) and (d), the shared kinship relation is profiled. The semantic contrast between have a parent and have a child resides in their opposite directionalities, and thus their TR-LM alignments.

2.1.3.3. The parameters of the spatial event

So far, I have discussed static spatial events, in which a TR is located with respect to a LM. However, a spatial event can also imply motion: in such events, the TR moves with respect either to a stable or to another moving entity (LM). In each case, one recognizes an asymmetrical relation between a TR and a LM. Several parameters can contribute to such asymmetrical relation, including the number of the moving entities, the direction of movement, the path of movement, containment, contact, orientation, or a combination of these (Svorou 1994: 24).

Motion events can be conceptualized as having directionality, or a deictic orientation. TRs can be directed toward or away from LMs: for example, the English verb to go implies a motion away from the speaker, whereas to come implies a direction toward the speaker. Furthermore, the directionality of certain entities can be specified on a vertical axis, such as in the following Italian verbs: salire ‘to go up’ entails an upward motion, while scendere ‘to go down’ a downward motion.

Читать дальше