The #MeToo movement gave a striking illustration both of the gender inequalities that characterize sexuality and of a change in attitudes that makes these inequalities less and less acceptable. Online dating bears witness to this complex nature of contemporary sexual norms. Dating services are a site for sexual exploration both for women and for men, but internet interactions are also profoundly gendered. This is clear from surveys, big data, and interviews that disclose a dual norm of male initiative and female sexual reserve . The last chapter looks at these traditional gender roles, which are reproduced online. It highlights the persistent double standard in sexual behavior and the different ways in which women and men are authorized to express desire. Although explicit consent is on the political agenda, the observation of actual dating behaviour shows that it is rarely expressed as such. On the contrary, sexual ambiguity remains the norm in heterosexual relations. The grey areas between consent and abuse are widening, especially online, where sexual desire is acted out but rarely pronounced.

The conclusion develops the main thesis of this book and puts it in a historical perspective. Online dating is both a cause and a consequence of a larger privatization of social life. As public socializing has decreased and, with it, also the opportunities for meeting new people, dating platforms attract users who wish to find partners outside their immediate surrounding. However, rather than installing a new public meeting venue – like the balls of the early twentieth century – online dating makes meeting partners more private than ever, turning it into a solitary and deeply personal matter.

Part I The Privatization of Dating

1 The History of Matchmaking

There are thousands of marriageable men and women of all ages capable of making each other happy, who never have a chance of meeting… Therefore, the desirability of having some organ through which ladies and gentlemen aspiring to marriage can be honorably brought into communication is too obvious to need a demonstration.

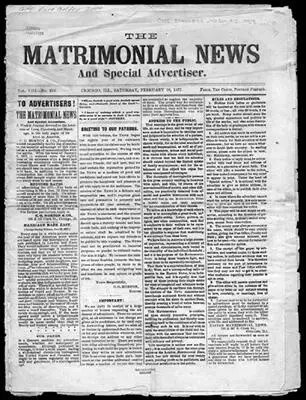

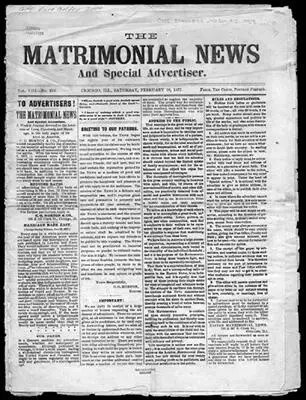

The Matrimonial News and Special Advertiser , October 1877

Our mission is to create new connections and bring the world closer together and help people meet others they otherwise wouldn’t have met.

Tinder, February 2017

Today’s dating sites and apps were born with the internet, but they can trace their distant origins to personal advertisements and forms of marriage brokerage that developed in the nineteenth century on both sides of the Atlantic. These early forms of commercial matchmaking have survived until today, but were supplemented in the 1980s by digital dating services such as the bulletin board systems (BBSs) in North America and the Minitel in France. Each of these services is a child of its time. They bear the mark of the sexual norms and matrimonial system they operated in, but also those of the economic and technical environment of their time. The spread is often tied to technological innovations, beginning with industrial printing, which made classified advertising popular, then moving on to early digital technologies, which spurred “computer dating” and the first online dating networks, and finally to the World Wide Web and mobile technology, with the websites and apps familiar to us today.

Many similarities can be found between these different types of dating services. The companies that operated in earlier forms of matchmaking were often the first to invest in new markets, hence features from older services have been passed on and adapted to new platforms. The filiation is noticeable not only in the production but also in the reception of dating services, as arguments directed against them can be found from time to time. The contemporary view that online dating has commodified intimate relations echoes a nineteenth-century outcry against matrimonial agencies and personal ads for turning marriage into a market. On the basis of work carried out by European and American historians and through an analysis of press archives, this chapter traces the origins of online dating. It shows that many features of these platforms and many debates around them, all considered radically new, are curiously similar to those features and debates found in their ancestors, sometimes 150 years old.

Marriage brokerage and personal ads

One of the first attested marriage advertisements was published in 1692 in the Athenian Mercury , an early British periodical (Cocks, 2015). Such advertisements were to remain rare until the second half of the nineteenth century, when “spouse wanted” ads became a staple of some newspapers in the English-speaking world, particularly the popular dailies of London and New York. Cheaper newspapers of mass circulation flourished as a result of the industrialization of publishing and population growth in urban centers. The dailies – typically, tabloids known as “the penny press” – were financed largely through advertising, which included classifieds. The personal columns soon began running matrimonial ads. The New York Herald , the largest daily newspaper in the United States at the time, published its first marriage ads in 1855 and was followed by the New York Times in 1860 (Epstein, 2010).

Similar advertisements flourished at the same time in London but, as historian Harry G. Cooks points out, “respectable papers like the Times or Morning Chronicle refused to carry matrimonial ads, thereby encouraging the development of a specialist press devoted solely to publishing them” (Cocks, 2015, p. 22). In Great Britain as in France, these “matrimonial papers” were closely linked to marriage brokerage, which spread around Europe in the nineteenth century (see Figure 1.1). Primarily the matrimonial agencies offered their services to a bourgeois clientele, taking commission on the dowry in cases of successful matches, but the papers ( feuilles d’annonces in French) allowed them to reach a broader and more socially diverse public (Gaillard, 2017).

Figure 1.1.Front page of The Matrimonial News and Special Advertiser (February, 1877)

While the development of newspaper publishing provided the material possibility to circulate classified advertisements, the impetus for mediatized matchmaking came from the social transformations of the nineteenth century. Industrialization and urbanization saw young people move away from their original environment and sever their ties to family- and neighborhood-based social networks, where they would traditionally find a spouse (Cocks, 2013, 2015). Matchmaking services allowed access to new potential partners, especially for those without the right social connections (Gaillard, 2020). However, the personal ads were also very much a product of the nineteenth century matrimonial system. In her doctoral research on French marriage brokerage and personal ads, Claire-Lise Gaillard stresses that, at the end of the nineteenth century, social status, possessions, properties, and dowry were more commonly mentioned in advertisements than the search for love and affection. Marriage was not simply a personal matter but a family concern. It is worth noticing that, at that time, almost a third of the ads published in France were written by parents on the lookout for a spouse for their daughters. Finding a suitable “match” was of utter importance, and the desired social attributes were therefore clearly articulated (Gaillard, 2020).

Contemporaries did not see the emergence of this new business in a favourable light. While ads and agencies were shaped by traditional matrimonial norms, they also clashed with codes of romantic love that had grown strong during the century – for instance that of “companionate marriage,” the ideal that “marriage should be based on the true love and mutual affection of marital partners rather than on family ties and parental negotiations” (Phegley, 2013, p. 130). The new matchmaking services came under attack on both sides of the Atlantic as newspapers, novels, and plays either mocked their vulgarity or condemned their negative impact, in terms not unlike those directed today against dating sites and apps. In fact the two most lively debates of the nineteenth century are strikingly similar to how online dating is framed today.

Читать дальше