Capacity utilisation (mostly used in manufacturing) measures the difference between production and production capability. Accounting for the fact that it is unlikely that an economy or company will function at 100 per cent capacity, 85 per cent is considered optimal. This provides a 15 per cent buffer against setbacks like equipment malfunction or resource shortages.

Olympians and professional sportspeople, too, know they will perform better at 85 per cent because they are more relaxed and can optimise muscle strength.

Hugh Jackman, in his preparation for and performance in the role of Wolverine, aimed to expend no more than 85 per cent of his energy, in the knowledge this would enable him to function optimally over extended production periods.

If we are to keep our own performance levels high and to optimise our resources and systems, we should be aiming for a maximum energy expenditure of 85 per cent.

This 15 per cent margin might seem arbitrary, or too little, and in many ways it's more about what happens in our heads than about watching the clock. Strive to feel as though you are performing at a steady pace, always with this tiny bit of room to breathe, not as though you are constantly catching up or struggling. You will feel in control instead of overwhelmed and exhausted from pushing yourself (or those around you) too far.

Of course, there will always be things outside your control: traffic jams, flight delays and other unexpected obstacles. Building in a 15 per cent buffer means you'll have greater capacity to manage disruptions.

This is how I arrived at the 1-Day Refund: 15 per cent of 7 is … 1! By applying some simple techniques and looking to shave 15 per cent off where you can, every week you can take back a whole day in your life!

Let's now explore this in more detail.

CHAPTER 1 We're busy addicts

We are all living in an epidemic of urgency and busyness. Unless we are flat out, working ridiculous hours, we are judged, and we often judge ourselves, as lazy or unproductive.

My friend Sharon is a senior manager in a large professional services organisation. She is also studying part time and has a seven‐year‐old daughter. She arrives for work most days around 8.15 am after the school drop‐off and leaves around 5.30 pm most afternoons to get back to afterschool care by the 6.30 pm deadline. Some days are pretty tight!

Despite this, she is productive and effective, but not always super social at work. Her boss, having noticed her arrival and departure times, recently pulled her aside and said, ‘People are noticing that you come in around 8.15 and leave around 5.30 most days. I've noticed as well. This would indicate to me that you don't have enough to do.’

To her credit, Sharon didn't react badly (I might have). She asked, ‘What is it that others, or you, feel I'm not doing? Have I missed some deadlines or is my work not up to scratch?’ Her boss said, ‘No, no, your work is fine. I get great feedback. It's just that others seem to work longer hours.’

Sharon replied,

I'm focused and efficient. I have to be. I have to be able to hold the job down and get home to my family. When the quality or quantity of my output starts to be less than what you are wanting, please let me know and we can have a discussion about my work hours then.

I'm thinking she may have looked like a woman on the edge, because her boss agreed and backed away … slowly.

But let's not blame Sharon's boss. Urgency is the new black. ‘Busy’ is the natural response to ‘How's work?’ The effect is cultures that pride themselves on ‘fast‐moving’ or ‘adaptive’ workplaces. But they are often white‐collar sweat shops, pushing people beyond their limits, and the result is burnout.

Matthew Bidwell, from the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, says of managers that when they can't measure outputs easily, they will measure inputs, such as how long you are spending at work.

Sharon told me that in her workplace, people are often judged not by their outputs but by how many hours they spend in the office. Some were even careful to arrive five minutes before, and to leave five minutes after, their boss. I'm sure you have a similar story — most of us do!

My brother, for example, was once chastised in a performance review because he was ‘too cheerful and didn't exhibit signs of stress’, which indicated to his boss that he didn't have enough to do. He couldn't possibly be adding value and remain cheerful! My brother left that job shortly after and was told by colleagues that people kept discovering how much he did in a day. ‘Bill used to do that’ was the answer to just about every question asked about tasks in the department.

The notion that busyness, franticness and stress are indicators of hard work and productivity has been around for over 2000 years. It seems that we are somehow wrong if we aren’t feeling these things. The Stoic philosopher Seneca, author of On the Shortness of Life , arguably the first ever management self‐help book, argued:

People are frugal in guarding their personal property; but as soon as it comes to squandering time, they are most wasteful of the one thing in which it is right to be stingy.

The industrial revolution specifically linked time to money as the advent of artificial lighting enabled 10‐ to 16‐hour workdays. It wasn't until Henry Ford introduced the eight‐hour workday, and profits increased exponentially, that people started to think differently about productivity by the hour. His profitable methods, in effect, refunded two to eight hours to his workers every day.

We are also driven by a work ethic deeply rooted in Judaeo‐Christian traditions that persuades us that to be ‘idle’ is to be ‘ungodly’.

Love not sleep, lest you come to poverty; open your eyes, and you will have plenty of bread. Proverbs 20:13

In a culture that values hard work and productivity, we feel we are ‘winning’ when we are going hard all the time. Because being busy increases our level of (self‐)importance and can become addictive, we may feel guilty or ashamed when we aren't busy doing stuff.

So we have a bit of conditioning to undo!

Instead of trading time for money, we need to trade energy for impact.

For example, we are all familiar with the model that says I give you x hours of my time in exchange for y dollars. But what if we instead focused on the idea that I give you energy, value and impact in return for dollars?

Instead of thinking about how many hours I need to put in, I think about exchanging the most valuable and impactful work each day.

Begin by asking yourself, where will I get the best return on my energy investment?

If you have a dog or a cat, watch them. They spend most of their time sleeping, with intermittent breaks for eating, pooping and running after a ball or a bird.

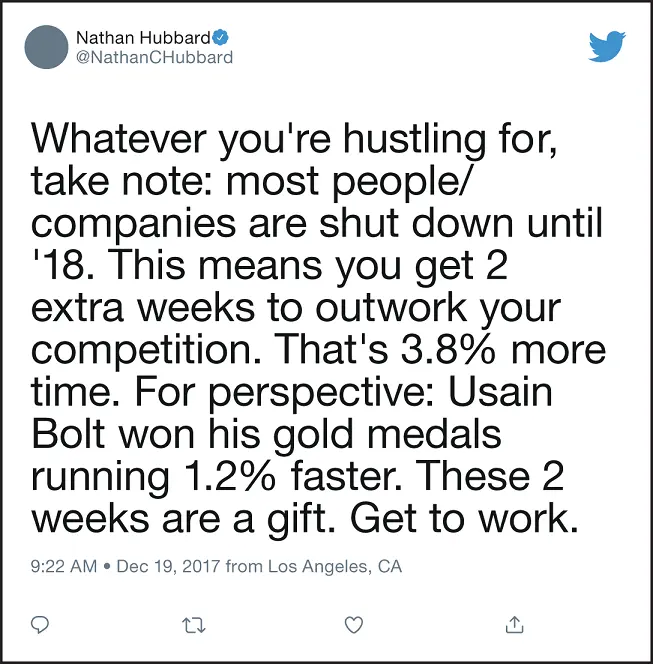

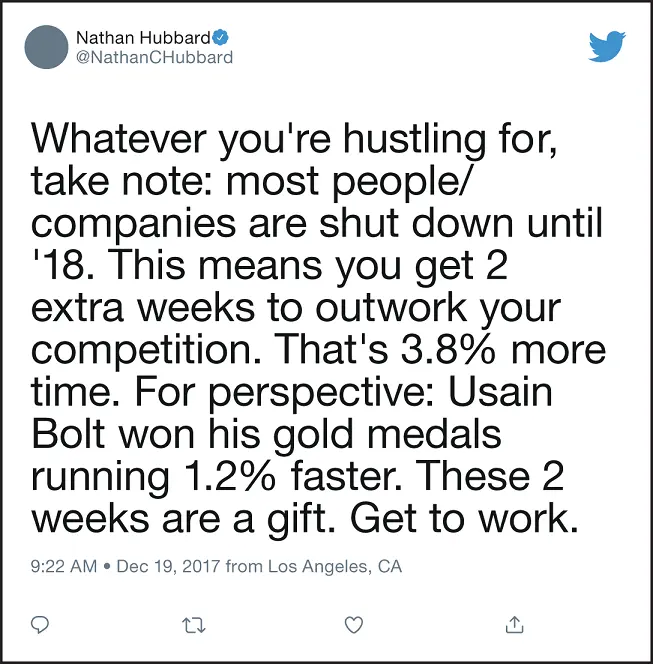

I think it's time to reframe ‘laziness’ and to enjoy life's pauses. Let's not be like Nathan Hubbard, former CEO of Ticketmaster, who in this tweet seems to be encouraging people to go hard over the holiday period.

For years researchers have proved time and time again the positive impact of restful activities:

Daydreaming, and even boredom, promote creative thinking.

Discovering non‐work‐related activities that both rejuvenate and excite you will provide the energy you need when it's time to get down to work. They also create an awesome contrast frame so you'll enjoy work‐related activities even more!

Читать дальше