1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...27 La Raccolta di Mendoza. Così chiamiamo la collezione di 63 pitture messicane fatta far dal primo Vicerè del Messico D. Antonio Mendoza, alle quali fece aggiungere da persone intendenti la loro interpretazione nelle lingue Messicana, e Spagnuola per mandarle all´Imperatore Carlo V.

The roles Clavijero and Mendoza play in the creation of their respective manuscripts could not be more different. The former is the intermediary of a bibliographical enterprise that seeks to transmit the truth about his land, which had been soiled by foreign authors. As such, he acts as a vehicle that allows the voices of truthful authors to be heard, thus restoring the splendor of his nation’s history. On the other hand, the latter is an active subject in the collection of information about Mexico; he is the author of a primary source. This idea allows us to consider the Codex Mendoza in the context of the bibliographical sources which Clavijero lists at the beginning of the Storia, and to suggest that the function of the document goes well beyond that of a mere work to be cited.

The bibliography

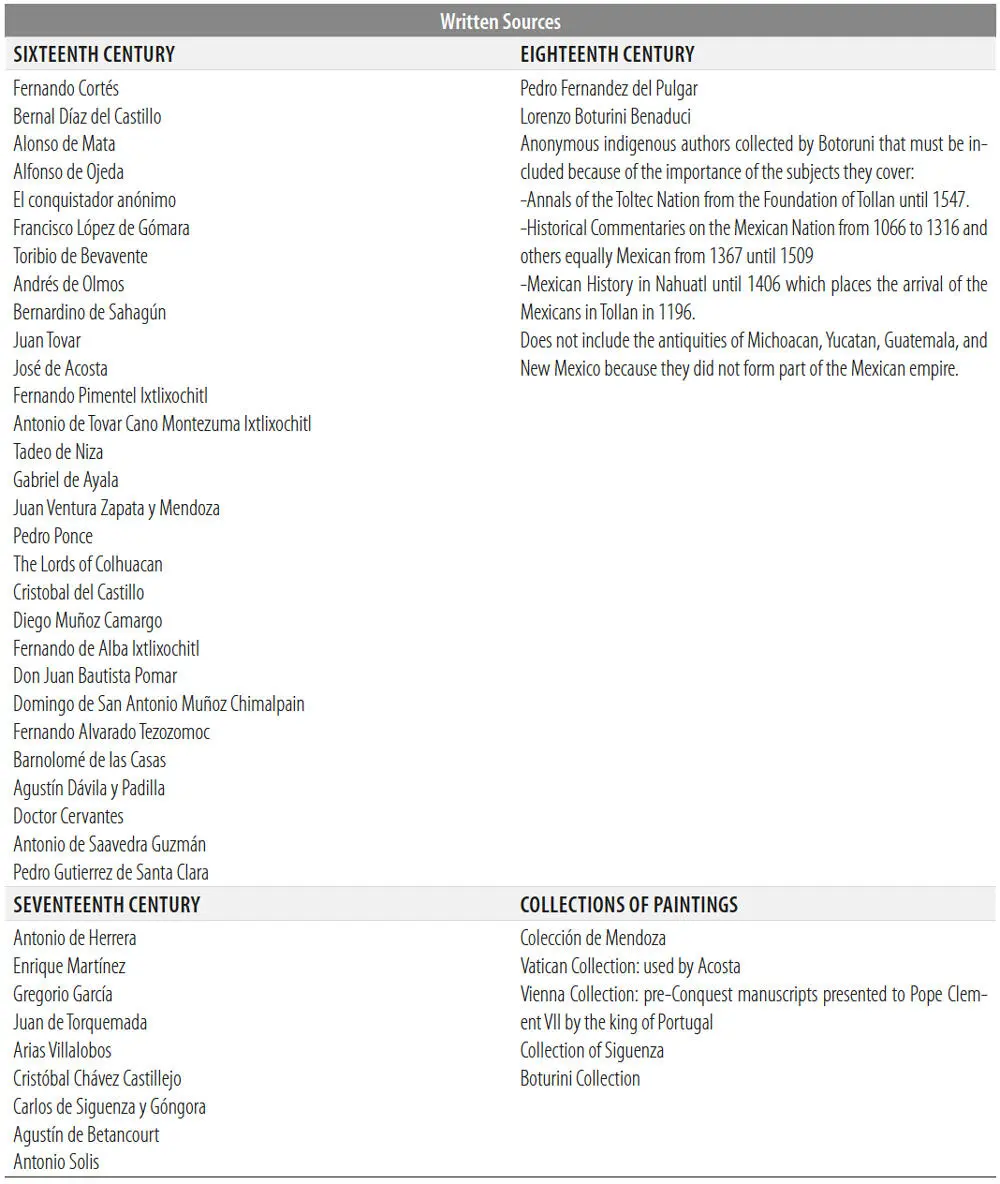

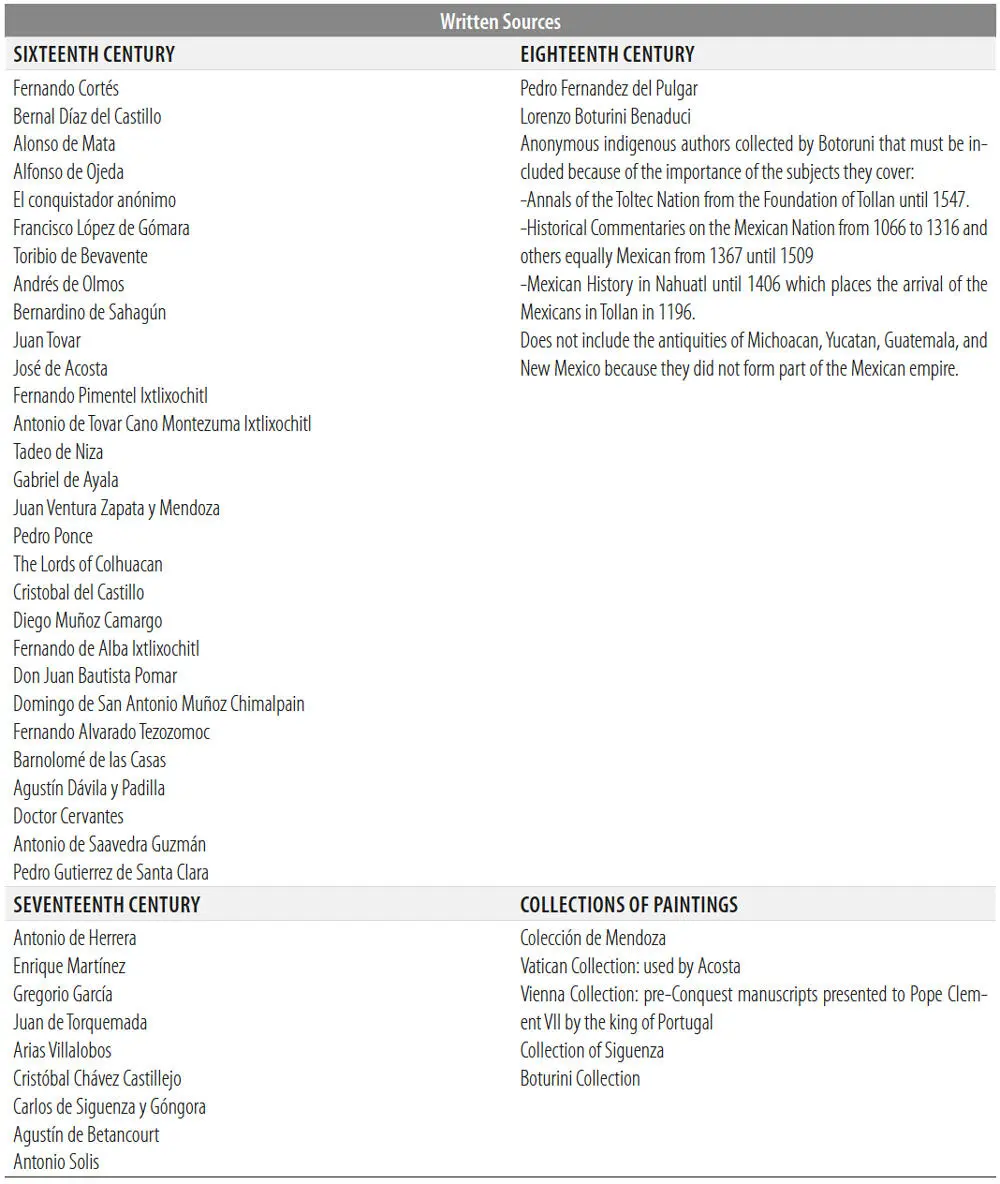

Immediately after the introduction, Clavijero lists forty-seven sources that he divides into two categories: the first is comprised of histories written by European and Mexican authors and the second includes collections of paintings (pictographic Mexican codices). The Codex Mendoza belongs to the latter.

As we can observe in table 2, Clavijero organizes his textual sources chronologically. Hence, he begins with Hernán Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo, two prominent authors who participated in the conquest of Mexico, and ends with the texts of Boturini, a famous eighteenth-century historian and collector. However, the way in which Clavijero organizes the Mexican pictographic manuscripts in his bibliography corresponds to a different logic. In this list, Clavijero (1780, 2:22) cites five pictographic manuscripts, which he refers to as collections of paintings useful for writing the history of Mexico. Four of these were introduced as pre-Columbian antiques when, in fact, they contain colonial elements. This sheds light on Clavijero’s bias in approaching this material and the value he sought to bestow upon it in the context of his bibliography: primary sources whose authority, because of their origin, was incontrovertible.

The fifth source on this list is the Codex Mendoza. Although Clavijero grouped it alongside documents of pre-Columbian origin, he never pretended that the Codex Mendoza was anything other than a colonial manuscript. Once more, what interests us here is not just the what but the how. Contrary to the way in which Clavijero organized his historical sources, by presenting the Codex Mendoza atop his list of pre-Columbian materials, he consciously reverts the chronological principle that had apparently guided the presentation of his bibliography, effectively enhancing the colonial manuscript he had just christened.

Thus, the bibliography for Clavijero’s Storia functions as a mirror in which textual sources are organized following a chronological progression from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, while pictographic manuscripts are organized in reverse chronological order. In this way, the Codex Mendoza, a colonial document that incorporated textual and pictographic materials and which was commissioned by the first viceroy of New Spain, acts as the bibliographical equivalent of a hinge between European and pre-Columbian histories. The how of this presentation is important. In the same way that Purchas had presented the manuscript a century earlier as an anonymous, but immensely valuable source (“the choicest of my Jewels”), Clavijero also sets the manuscript apart from the group to which he assigns it by ignoring the order he had already established for the presentation of his sources and by attributing it to Antonio de Mendoza. For the purposes of nominally considering the inclusion of this manuscript in the Storia’s bibliography, the order in which it appears is irrelevant. However, when considered in conjunction with the name bestowed upon the manuscript, the historical context in which Clavijero’s work appears, and the function Clavijero assigns it in his Storia (as a vehicle for his nation-building project), the gesture cannot be ignored.

Table 2: The bibliographic sources of the Storia Antica del Messico

On one hand, by incorporating both textual and pictographic materials, the Codex Mendoza functions as a desirable transition between colonial and pre-Columbian sources and hence fulfills a practical role in the presentation of the bibliography. On the other, by actively linking the manuscript with the first viceroy of New Spain, calling it “the collection (raccolta) of Mendoza,” and keeping in mind the viceroy’s reputation as a humanist and a statesman, whether consciously or unconsciously, Clavijero bestows upon him responsibility over the contents of the manuscript, even if he had not been their material author. The identification of Mendoza as the man responsible for the manuscript marks it as a preeminent, quasi-foundational document. By making Antonio de Mendoza responsible for the manuscript, Clavijero sets up a narrative arc for his bibliography around the historical moment in which ancient, pictographic Mexico converges with modern, textual Mexico, and identifies him with the birth of the Viceroyalty of New Spain as a political structure that could serve as the foundation for the modern Mexican nation. Henceforth, scholars of Mexico could access specific truths pertaining ancient Mexico by means of a “return to the origin” of New Spain, which combined royal authority embodied in the figure of the viceroy and indigenous voices articulated in the manuscript’s images and texts. This, however, raises several questions: Why Mendoza? Why did Clavijero not attribute the patronage of the manuscript to Luis de Velasco, Hernán Cortés, Vasco de Quiroga, or any other notable figure of the period whose authority could have been equally desirable for enhancing the value of the manuscript as a primary source of unquestionable reputation?

Don Antonio de Mendoza

The first viceroy of New Spain is one of the most famous personages of Spanish colonial history. The son of Íñigo López de Mendoza, Captain General of Granada, don Antonio received a privileged education. He was tutored by the notable chronicler Pedro Mártir de Anglería, and his family’s close connections to the Castilian crown allowed him access to the most intimate circles of the Spanish court (Aiton 1927). Among other prestigious positions he held throughout his life in Europe, Mendoza was a gentleman of the king’s chamber to Charles I and ambassador to Vienna, one of the most important European capitals of Habsburg Europe. However, it is not only his lineage or his position as the first viceroy of New Spain that set him apart from other administrators of the crown in the New World, but also his reputation as a humanist. Together, these conditions single him out in early colonial history, thus making Clavijero’s attribution of the manuscript to him, rather than to any of the other notable personages of the period, all the more beneficial for the codex that bears his name.

Mendoza’s particular profile as the viceroy and a man of letters is underscored by contemporary authors including Friar Jerónimo de Alcalá and Juan de Matienzo. In his prologue to the Relación de Michoacán, Alcalá ([1540] 1980, 5–6) calls Mendoza “elected by God” to rule, and highlights Mendoza’s virtues of magnanimity, prudence, affability, severity, and zeal for the implementation of the Christian faith he embodied. These epithets appear to echo the style in which Juan de Matienzo speaks of Mendoza in his Gobierno del Perú, in which he describes him as a “light and mirror for all future viceroys” (Matienzo [1567] 1967, 207). In speaking of Mendoza in these terms, both authors implicitly refer to widely known and well-established ideas regarding the practical and symbolic role of the Castilian viceroy. Quoting legal treatises of the period by authors such as Rafael de Vilosa, Juan de Solórzano, Erasmus of Rotherdam, Mercurino Gattinara, and others, Alejandro Cañeque’s The King’s Living Image (2004, 25) and Manuel Rivero Rodríguez’s La edad de oro de los virreyes (2011) highlight several of the fundamental elements of the viceroyal ideology. For example, the viceroy was not only considered a high-ranking administrator, but also the king’s alter ego; the viceroy’s decrees, favors, and commissions were considered to be of the king himself. The attribution of the commission of the manuscript to the viceroy with the goal of elevating its value is a gesture that even Purchas seems to have intuitively understood, as is demonstrated by the well-known text in which he explains the way the manuscript reached Thevet, and which Clavijero deemed desirable when he included the manuscript as one of his sources. In attributing the manuscript to Mendoza over other viceroys, Clavijero endowed the manuscript not only with the reputation reserved for viceroyal commissions, but with that of Mendoza’s own reputation, whose excellence as a governor and an intellectual were unmatched by his successors.

Читать дальше