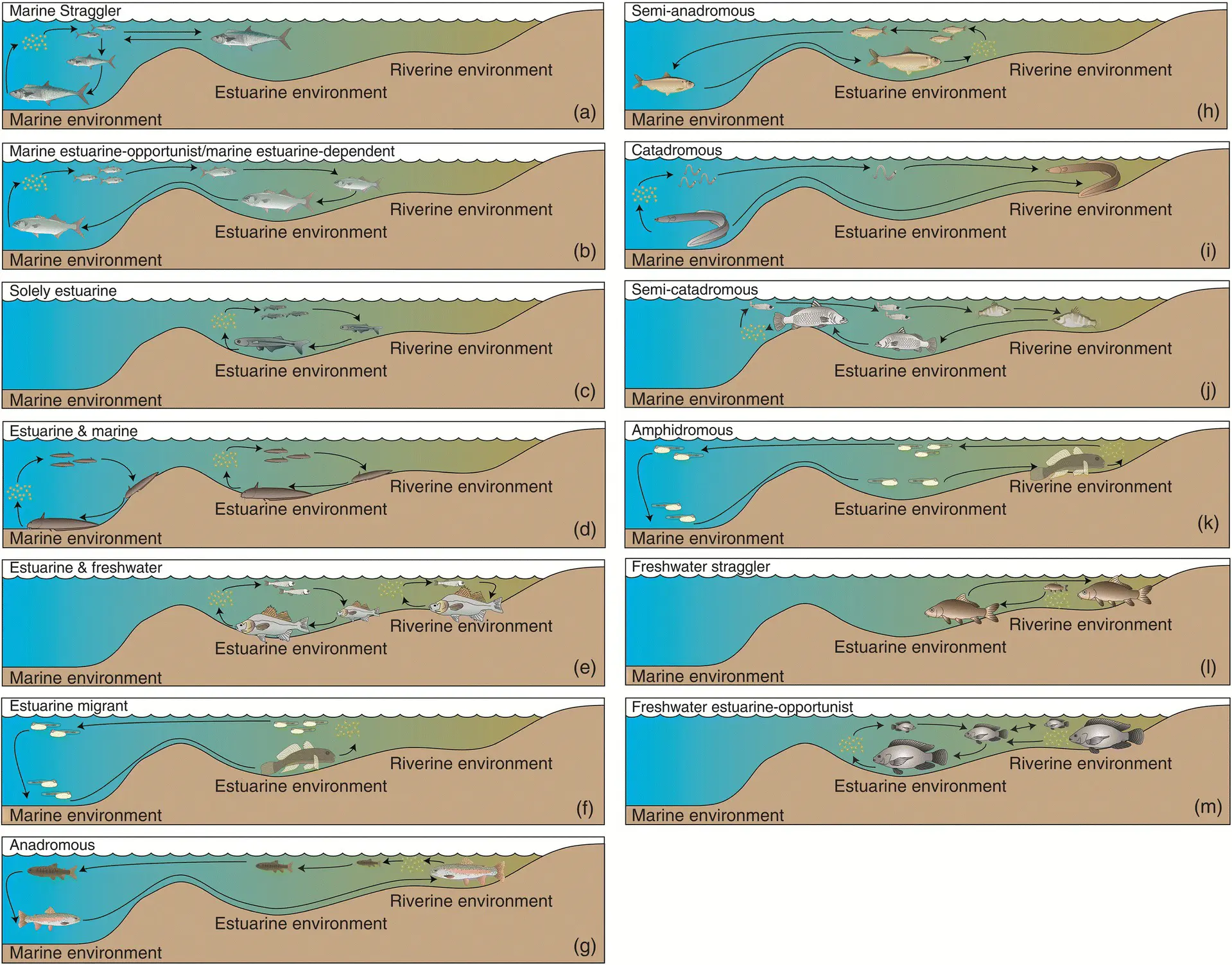

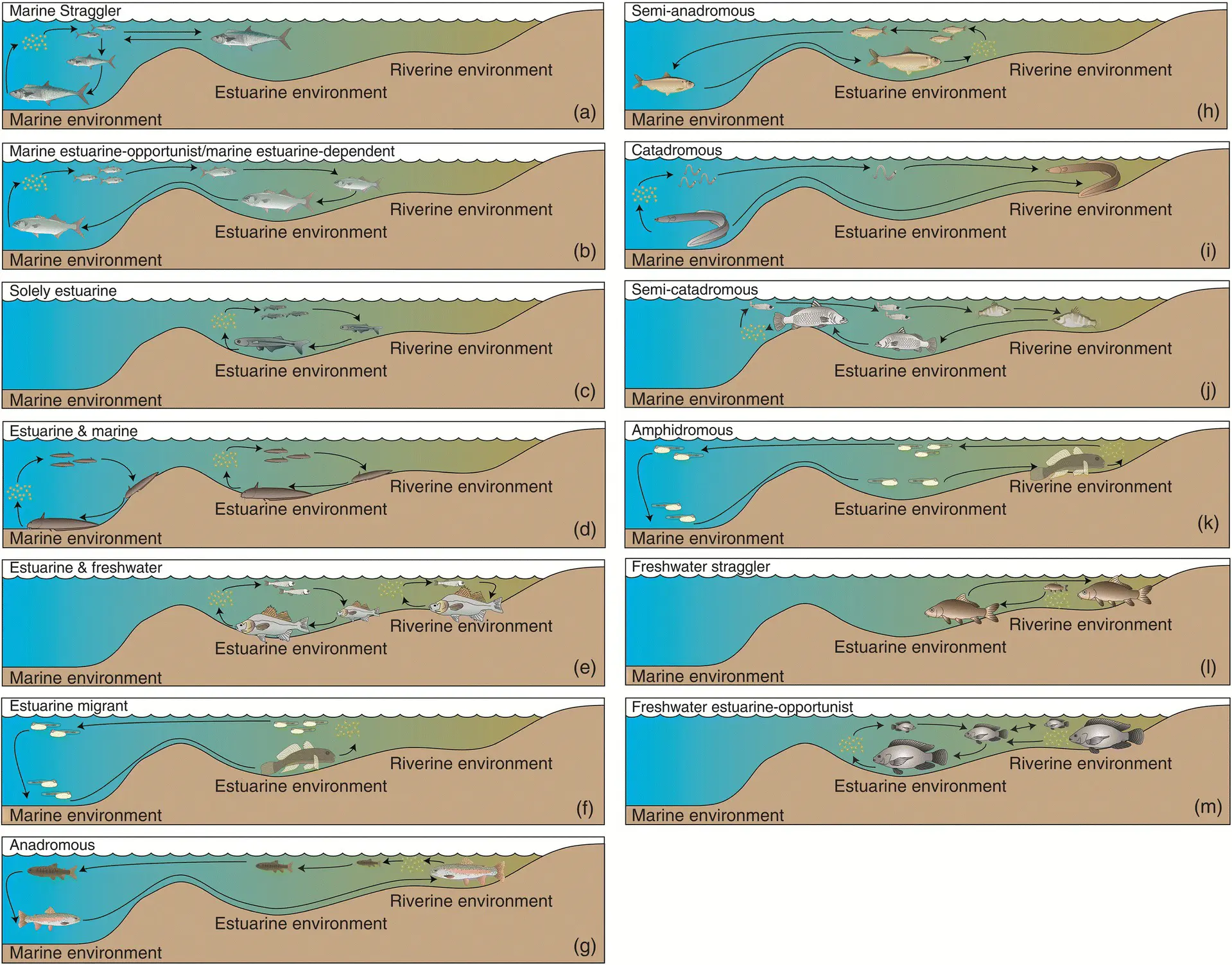

Figure 2.10 Life cycle guilds of estuary‐associated fishes, based on the review by Potter et al. (2015a); (a) marine straggler, (b) marine estuarine‐opportunist/estuarine‐dependent, (c) solely estuarine, (d) estuarine & marine, (e) estuarine & freshwater, (f) estuarine migrant, (g) anadromous, (h) semi‐anadromous, (i) catadromous, (j) semi‐catadromous, (k) amphidromous, (l) freshwater straggler, (m) freshwater estuarine‐opportunist.

Subsequently, Potter et al. (2015a) updated the Estuarine Use Functional Group (EUFG) component of Elliott et al. (2007) and thus it now includes four broad ‘umbrella’ categories: marine, estuarine, diadromous and freshwater ( Table 2.2). Each of these categories contains two or more guilds, which represent characteristics associated with the locations of spawning, feeding and/or refuge and, in some cases, involve migratory movements between estuaries and other ecosystems. The Feeding Mode Functional Group (FMFG), which defines the primary method of feeding used by a given species, is presented in Table 2.3and the Reproductive Mode Functional Group (RMFG), which indicates how and, in some cases, where an estuarine species reproduces, is outlined in Table 2.4(Elliott et al. 2007).

Within each of the above major categories, subcategories have been defined and, where possible, examples given that illustrate the use of that mode by fishes from estuaries in different biogeographical regions (Elliott et al. 2007, Potter et al. 2015a). In this way, the approach can be used to show similarities or differences in the global estuarine fish community structure, based primarily on the functional guilds encountered.

2.4.1 Estuarine Use Functional Group (EUFG)

Estuaries have well‐defined roles as areas for fish feeding and refuge and as migration routes, fundamental properties now shown to occur worldwide, e.g. for North America (Nordlie 2003), the tropical Indo‐Pacific (Blaber 2000), Europe (Elliott & Hemingway 2002), tropical Africa (Albaret et al. 2004), southern Australia (Potter & Hyndes 1999) and subtropical and temperate southern Africa (Whitfield 1999). The seasonal and spatial occurrence of species and their biological attributes are sometimes well known (e.g. Claridge et al. 1986) such that taxa can be assigned to guilds, which denote the primary estuarine use made by different species ( Table 2.2). These terms have been widely used and consolidated by Elliott et al. (2007) and Potter et al. (2015a) to include more recent information and account for subtle differences worldwide. The revisions indicate the migration patterns, physiological adaptations required to occupy estuaries, and the multifaceted use of these areas by fish species, including stragglers from adjacent freshwater and marine environments.

The selected categories outlined in Table 2.2and Figure 2.10cover all the dominant groups of fishes found in estuaries, as well as describing the links between the estuary and areas downstream (along the coast and in the open sea) and upstream (into freshwaters) of the estuarine environment. As expected, much of the estuarine fish community originates from marine areas and this is reflected in the guild approach. This approach has previously taken several different forms, for example the bioecological categories and ‘affinities’ defined by Albaret (1999) for tropical African estuaries and lagoons distributed according to two gradients. These gradients, of species with a marine affinity and species with a freshwater affinity, indicate the sources of the species inhabiting the estuary and thus the influence of natural and anthropogenic influences external to the estuary, e.g. impoundment of catchment rivers affecting those estuarine species with a freshwater affinity (Chícharo & Chícharo 2006).

Some marine and freshwater species have a well‐defined and regular use of estuaries, whether as a nursery area, seasonal or reproductive migrations, or use as a refuge. However, other marine and freshwater species occur ‘occasionally’ (Albaret 1999) or ‘adventitiously’ (e.g. Elliott & Hemingway 2002), terms previously used to denote an almost accidental or at best an unexplained and infrequent use of estuaries. The term ‘stragglers’ has been used mainly in a southern hemisphere context (e.g. Potter et al. 1990) and is preferred here to denote a numerically insignificant and almost accidental intrusion by species from either coastal or freshwater areas and for species that are predominantly stenohaline marine or freshwater in terms of their salinity tolerances. Hence, these guild categories frequently relate to salinity tolerances of the species, thus reflecting the physiologically stressful nature of estuaries (e.g. Martino & Able 2003). The majority of stragglers are thus restricted to the ends of the salinity continuum (seawater or freshwater) and generally occupy an estuary in low numbers for only very short periods of time and in limited areas ( Figure 2.10).

Table 2.2 Estuarine Usage Functional Group (EUFG) (modified from Potter et al. 2015a).

| Category and guild |

Definition |

Examples |

| Marine category |

Species that spawn at sea |

|

| Marine straggler |

Typically enter estuaries sporadically and in low numbers and are most common in the lower reaches where salinities typically do not decline far below ~35. Belong to populations in marine waters and are often stenohaline |

Scomberomorus maculatus (Scombridae) Lithognathus mormyrus (Sparidae) Lutjanus colorado (Lutjanidae) |

| Marine estuarine‐opportunist |

Regularly enter estuaries in substantial numbers, particularly as juveniles, but use, to varying degrees, coastal marine waters as alternative nursery areas |

Pomatomus saltatrix (Pomatomidae) Mugil cephalus (Mugilidae) Dicentrarchus labrax (Moronidae) |

| Marine estuarine‐dependent |

Species whose juveniles require sheltered estuarine habitats and are thus not present along exposed coasts where they spend the rest of their life |

Rhabdosargus holubi (Sparidae) Monodactylus falciformis (Monodactylidae) |

| Estuarine category |

Species with populations in which the individuals complete their life cycles within the estuary |

|

| Solely estuarine |

Species found only in estuaries |

Atherinosoma elongatum (Atherinidae) Pomatoschistus microps (Gobiidae) Gilchristella aestuaria (Clupeidae) |

| Estuarine & marine |

Species also represented by marine populations |

Cnidoglanis macroceplalus (Plotosidae) Clinus supercilious (Clinidae) Syngnathus temminckii (Syngnathidae) |

| Estuarine & freshwater |

Species also represented by freshwater populations |

Morone americana (Moronidae) Leptatherina wallacei (Atherinidae) Glossogobius callidus (Gobiidae) |

| Estuarine migrant |

Species that spawn in estuaries but may be flushed out to sea as larvae and later return at some stage to the estuary |

Caffrogobius gilchristi Gobiidae) Psammogobius knysnaensis (Gobiidae) |

| Diadromous category |

Fish species which migrate between the sea and fresh water |

|

| Anadromous |

Spend most of their life growing at sea and migrate into rivers to spawn |

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Salmonidae) Petromyzon marinus (Petromyzontidae) Anodontostoma chacunda (Clupeidae) |

| Semi‐anadromous |

Spawning run from the sea extends only as far as the upper estuary rather than into fresh water |

Nematalosa vlaminghi (Clupeidae) Dorosoma petenense (Clupeidae) Tenualosa toli (Clupeidae) |

| Catadromous |

Spend their trophic life in fresh water and subsequently migrate out to sea to spawn |

Anguilla rostrata (Anguillidae) Anguilla anguilla (Anguillidae) Anguilla bicolor (Anguillidae) |

| Semi‐catadromous |

Spawning run extends only as far as downstream estuarine areas rather than into the marine environment |

Lates calcarifer (Latidae) Liza abu (Mugilidae) |

| Amphidromous |

Spawn in fresh water, with the larvae flushed out to sea, where feeding occurs, followed by a migration back into fresh water, where most somatic growth and spawning occurs |

Sicyopterus stimpsoni (Gobiidae) Galaxias fasciatus (Galaxiidae) Plecoglossus altivelis (Plecoglossidae) |

| Freshwater category |

Species that spawn in freshwater |

|

| Freshwater straggler |

Found in low numbers in estuaries and whose distribution is usually limited to the low salinity, upper reaches of estuaries |

Carassius auratus (Cyprinidae) Coptodon rendalli (Cichlidae) Esox lucius (Esocidae) |

| Freshwater estuarine‐opportunist |

Found regularly and in moderate numbers in estuaries and whose distribution can extend well beyond the oligohaline sections of these systems |

Oreochromis mossambicus (Cichlidae) Redigobius dewaali (Gobiidae) |

In contrast, those fish taxa with euryoecious tolerances (i.e. wide tolerances to several environmental variables), especially euryhaline characteristics, are best adapted to an estuarine existence (Whitfield 2019). For example, both estuarine (ES) and marine estuarine‐opportunist/dependent (MEO/MED) species are euryoecious and have the ability to tolerate the spatially and temporally widely varying conditions found within estuaries. This feature was shown by the multivariate analysis of salinity tolerances amongst estuarine fishes carried out by Bulger et al. (1993), where estuarine salinity regions were defined according to their biological characteristics. In that analysis, many estuarine species were shown to have a wide salinity tolerance such that salinity regions in estuaries were overlapping in distribution. One family with species able to persist in extremely high salinities are the atherinids, with Atherinosoma elongatum and its congener Atherinosoma microstoma being recorded in salinities up to 150 in estuaries in southern Australia (Tweedley et al. 2019). Moreover, another atherinid, Menidia beryllina , was observed in salinities of 120 in the Laguna Tamaulipas, Texas, USA (Copeland 1967).

Читать дальше