FIGURE 1.2 Newer EIP model.

Modified from Haynes et al., (2002).

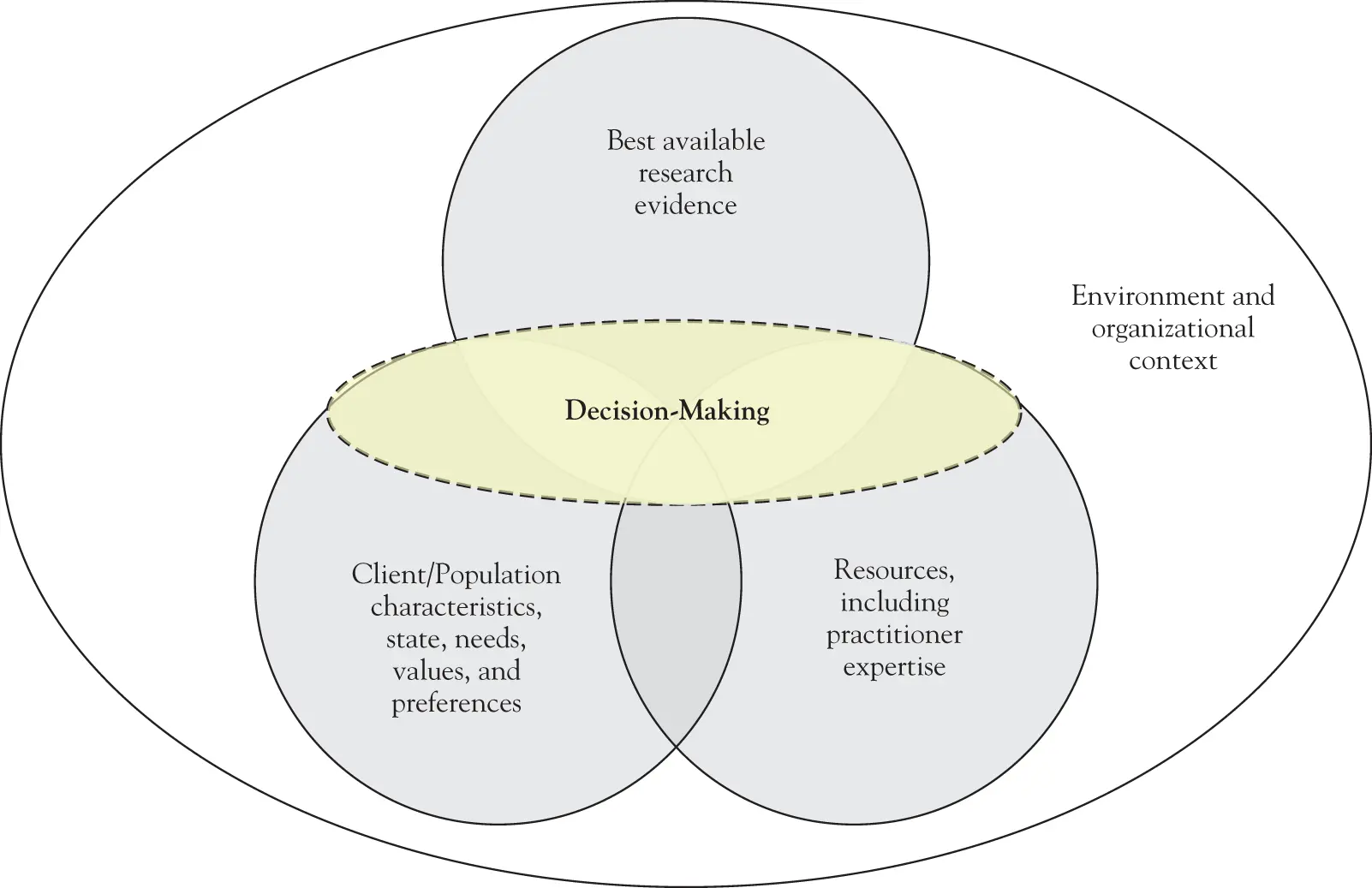

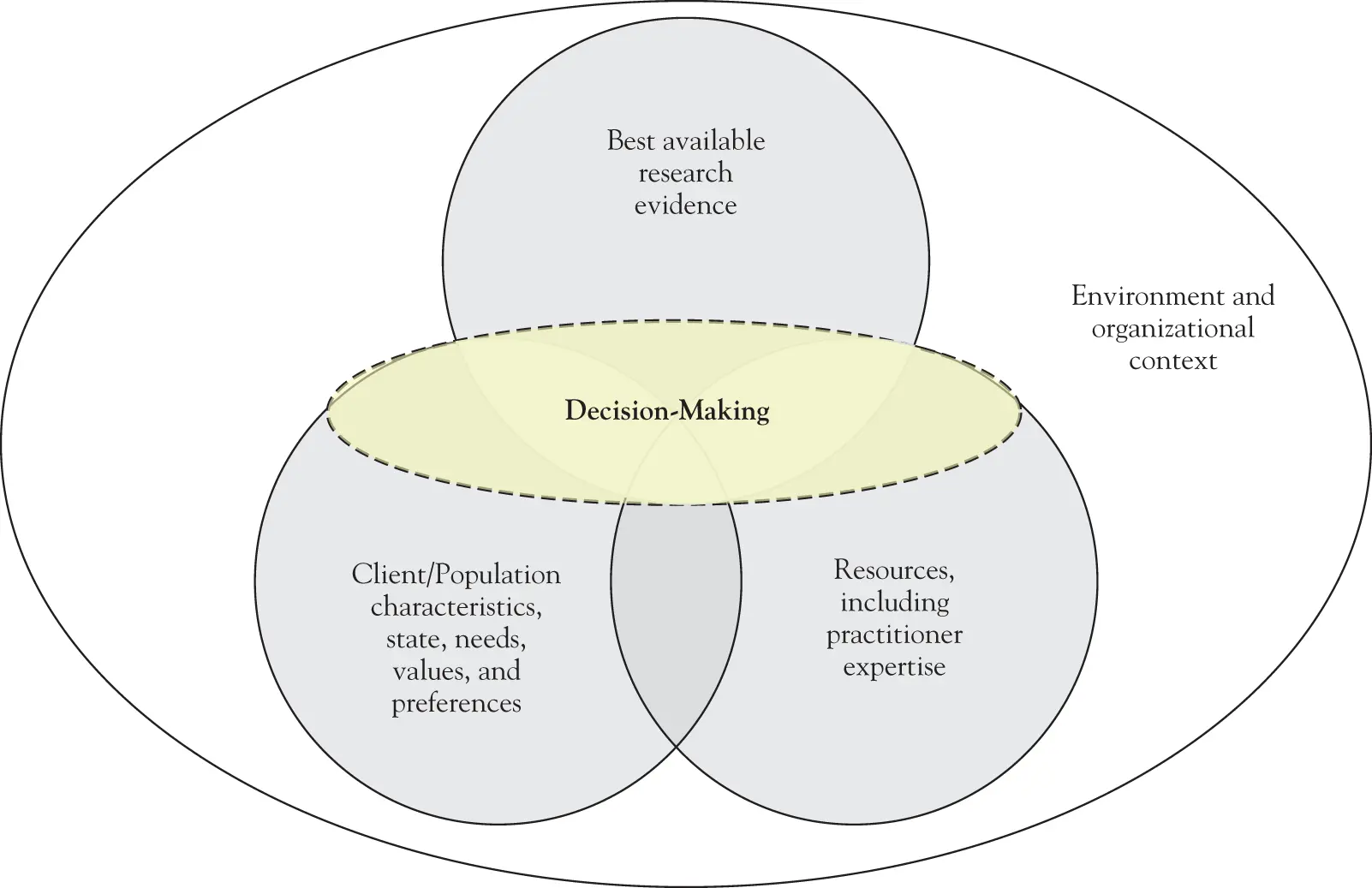

FIGURE 1.3 The transdisciplinary model of evidence-informed practice.

From “Toward a Transdisciplinary Model of Evidence-Based Practice,” by Satterfield et al. (2009). Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

The cyclical process of EIP can be conceptualized as involving the following five steps: (a) formulating a question, (b) searching for the best evidence to answer the question, (c) critically appraising the evidence, (d) selecting an intervention based on a critical appraisal of the evidence and integrating that appraisal with practitioner expertise and awareness of the client's preferences and clinical state and circumstances, and (e) monitoring client progress. Depending on the outcome observed in the fifth step, the cycle may need to go back to an earlier step to seek an intervention that might work better for the particular client, perhaps one that has less evidence to support it, but which might nevertheless prove to be more effective for the particular client in light of the client's needs, strengths, values, and circumstances. Chapter 2examines each of these five steps in more detail.

1.3.5 What Are the Costs of Interventions, Policies, and Tools?

When asking which approach has the best effects, we implicitly acknowledge that for some target problems there is more than one effective approach. For example, the book Programs and Interventions for Maltreated Children and Families (Rubin, 2012) contains 20 chapters on 20 different approaches whose effectiveness with maltreated children and their families has been empirically supported. Some of these programs and interventions are more costly than others. Varying costs are connected to factors such as the minimum degree level and amount of experience required in staffing, the extent and costs of practitioner training, caseload maximums, amount number of treatment sessions required, materials and equipment, and so on. The child welfare field is not the only one in which more than one empirically supported approach can be found. And it is not the only one in which agency administrators or direct service practitioners are apt to deem some of these approaches to be unaffordable. An important part of practitioner expertise includes knowledge about the resources available to you in your practice context. Consequently, when searching for and finding programs or interventions that have the best effects, you should also ask about their costs. You may not be able to afford the approach with the best effects, and instead may have to settle for one with less extensive or less conclusive empirical support.

But affordability is not the only issue when asking about costs. Another pertains to the ratio of costs to benefits. For example, imagine that you were to find two empirically supported programs for reducing dropout rates in schools with high dropout rates. Suppose that providing the program with the best empirical support – let's call it Program A – costs $200,000 per school and that it is likely to reduce the number of dropouts per school by 100. That comes to $2,000 per reduced dropout. In contrast, suppose that providing the program with the second best empirical support – let's call it Program B – costs $50,000 per school and that it is likely to reduce the number of dropouts per school by 50. That comes to $1,000 per reduced dropout – half the cost per dropout than Program A.

Next, suppose that you administer the dropout prevention effort for an entire school district that contains 20 high schools, and that your total budget for dropout prevention programming is $1 million. If you choose to adopt Program A, you will be able to provide it in five high schools (because 5 × 200,000 = one million). Thus, you would be likely to reduce the number of dropouts by 500 (i.e., 100 in each of five schools). In contrast, if you choose to adopt Program B, you will be able to provide it in 20 high schools (because 20 × 50,000 = one million). Thus, you would be likely to reduce the number of dropouts by 1,000 (i.e., 50 in each of 20 schools). Opting for Program B instead of Program A, therefore, would double the number of dropouts prevented district wide from 500 to 1,000. But does that imply that opting for Program B is the best choice? Not necessarily. It depends on, in part, just how wide the gap is between the strength of evidence supporting each approach. If you deem the evidence supporting Program B to be quite skimpy and unconvincing despite the fact that it has the second best level of empirical support, while deeming the evidence supporting Program A to be quite strong and conclusive, you might opt to go with the more costly option (Program A) that is likely to prevent fewer dropouts, but which you are more convinced will deliver on that promise in light of its far superior empirical support. (In fact, if you can show funders that Program A reduces 100 dropouts per school, you'd have a decent chance of getting future funding enabling you to provide it in more than five schools, and perhaps all 20.)

Depending on such factors as your budget and your assessment of the quality and amount of empirical support each approach has, in some situations you might opt for a less costly program with less empirical support, whereas in other situations you might opt for a more costly program with better empirical support. It's likely to be a judgment call. The important point is to remember to consider the costs and likely benefits of each approach in light of what you can afford, instead of asking about the best effects only, or the degree of empirical support, only.

1.3.6 What about Potential Harmful Effects?

In addition to cost considerations, as you search for the approach with the best effects, you should also bear in mind the possibility of harmful effects. There are two reasons for this. One is that some programs and interventions that were once widely embraced by helping professionals were found to be not only ineffective but actually harmful. Examples include Scared Straight programs; critical incidents stress debriefing; psychodynamic, in-depth insight-oriented psychotherapy for schizophrenia; and treating dysfunctional family dynamics as the cause of schizophrenia. (For a discussion of these approaches, see Rubin, 2012; and Rubin & Babbie, 2011.)

Some approaches that are effective overall can be harmful – or contraindicated – for certain types of clients. For example, consider two empirically supported treatment approaches for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the early 1990s, trainees in one of these treatment approaches – eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) – were cautioned to check for whether the client had a dissociative order or physical eye ailments before providing it because it could be harmful for such clients. The other empirically supported treatment approach – prolonged exposure therapy – can have unintended harmful effects for people whose PTSD is comorbid with suicidality or substance abuse, in that recalling and retelling in minute detail their traumatic events before their substance abuse or suicide risk is resolved can exacerbate both of those conditions (Courtois & Ford, 2009; Rubin & Springer, 2009). Even if a client doesn't have any characteristics that are a risk for harm from interventions, every client is different. In some cases, clients may experience an intervention negatively or may have a mix of both positive and negative outcomes – even if research suggests that the intervention on the whole works well for many people. The need to consider such harmful effects pertains to the aspect of EIP discussed earlier in this chapter – regarding the importance of integrating the best research evidence with your practice expertise and knowledge of client attributes, including the assessment intervention outcomes for each client individually.

Читать дальше