Allen Rubin - Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Allen Rubin - Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice

Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice, Third Edition

Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice

Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Is the instrument feasible? If you are monitoring a child's progress from week to week regarding behavioral and emotional problems, a 100-item checklist probably will be too lengthy. Parents and teachers may not want to take the time to complete it every week, and if you are asking the child to complete it during office visits, there go your 45 minutes. If your clients can't read, then a written self-report scale won't work.

Is the instrument culturally sensitive? The issue of an instrument's cultural sensitivity overlaps with the issue of feasibility. If your written self-report scale is in English, but your clients are recent immigrants who don't speak English, the scale will be culturally insensitive and unfeasible for you to use. But cultural insensitivity can be a problem even if your scale is translated into another language. Something might go awry in the translation. Even if the translation is fine, certain phrases may have different meanings in different cultures. If most English-speaking Americans are asked whether they feel blue, they'll probably know that blue means sad. Translate that question into Spanish and then ask “Esta azul? to a Spanish-speaking person who just crossed the border from Mexico, and you might get a very strange look. Cultural sensitivity also overlaps with reliability and validity. If clients don't understand your language, you might get a different answer every time you ask the same question. If clients think you are asking whether their skin is blue, they'll almost certainly say “no” even if they are in a very sad mood and willing to admit it.

Many studies can be found that assess the reliability and validity of various assessment tools. Some also assess sensitivity. Although there are fewer studies that measure cultural sensitivity, the number is growing in response to the current increased emphasis on cultural responsivity and attention to diversity in the human services professions.

1.3.4 Which Intervention, Program, or Policy Has the Best Effects?

Perhaps the most commonly posed type of EIP question pertains to selecting the most effective intervention, program, or policy. As noted previously, some managed care companies or government agencies define EBP (or EIP) narrowly and focus only on this effectiveness question. They will call your practice evidence -informed only if you are providing a specific intervention that appears on their list of preferred interventions, whose effectiveness has been supported by a sufficient number of rigorous experimental outcome evaluations to merit their “seal of approval” as an evidence-informed intervention. As noted earlier, this definition incorrectly fails to allow for the incorporation of practitioner expertise and patient values. The EIP process, however, allows practitioners to choose a different intervention if the “approved” one appears to be contraindicated in light of client characteristics and preferences or the realities of the practice context.

The process definition of EIP is more consistent with the scientific method, which holds that all knowledge is provisional and subject to refutation. In science, knowledge is constantly evolving. Indeed, at any moment a new study might appear that debunks current perceptions that a particular intervention has the best empirical support. For example, new studies may test interventions that were previously untested and therefore of unknown efficacy, or demonstrate unintended side effects or consequences that reduce the attractiveness of existing “evidence-informed” interventions when disseminated more broadly in different communities. Sometimes the published evidence can be contradictory or unclear. Rather than feel compelled to adhere to a list of approved interventions that predates such new studies, practitioners should be free to engage in an EIP process that enables them to critically appraise and be informed by existing and emerging scientific evidence. Based on practitioner expertise and client characteristics, practitioners engaging in the EIP process may choose to implement an intervention that has a promising yet less rigorous evidence base. Whether or not the chosen intervention has a great deal of evidence supporting its use, practitioners must assess whether any chosen intervention works for each individual client. Even the most effective treatments will not work for everyone. Sometimes the first-choice intervention option doesn't work, and a second or even third approach (which may have less research evidence) is needed.

Thus, when the EIP question pertains to decisions about what intervention program or policy to provide, practitioners will attempt to maximize the likelihood that their clients will receive the best intervention possible in light of the following:

The most rigorous scientific evidence available.

Practitioner expertise.

Client attributes, values, preferences, and circumstances.

Assessing for each case whether the chosen intervention is achieving the desired outcome.

If the intervention is not achieving the desired outcome, repeating the process of choosing and evaluating alternative interventions.

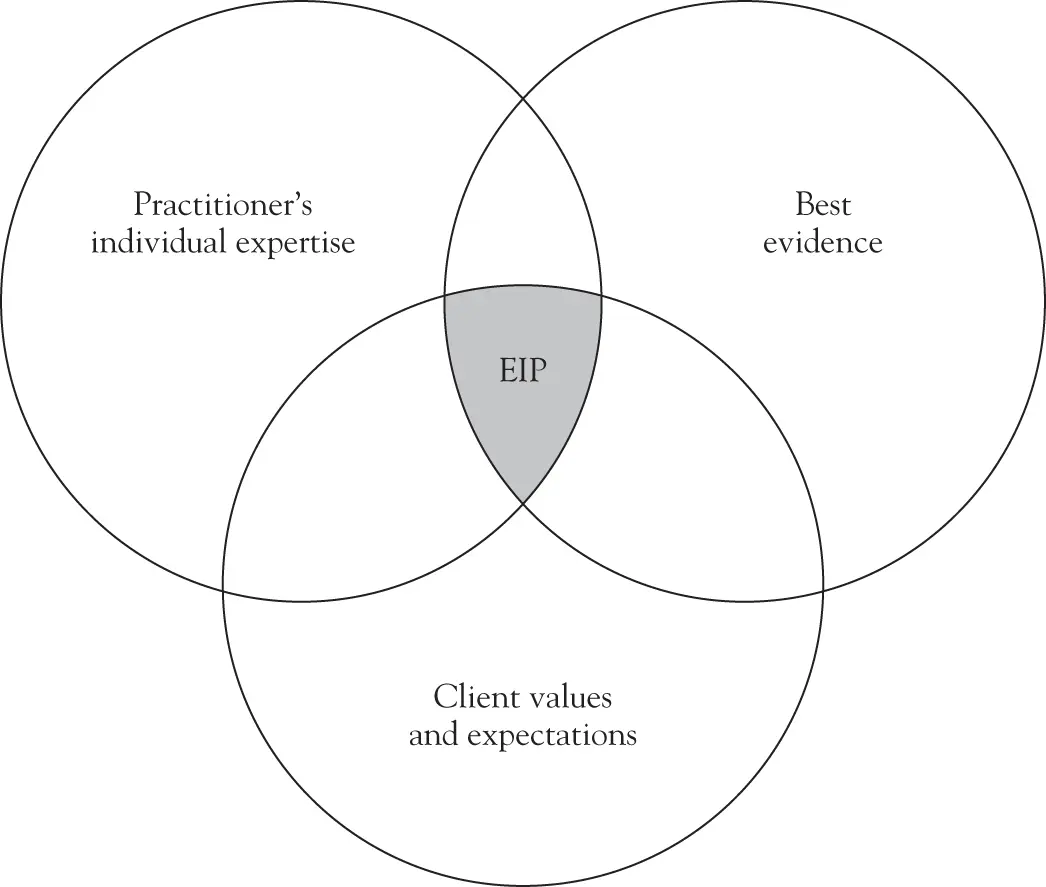

FIGURE 1.1 Original EIP model.

Figure 1.1shows the original EIP model, illustrating the integration of current best evidence, practitioner's individual expertise, and client values and expectations. Unlike misconceptions of EIP that characterized it as requiring practitioners to mechanically apply interventions that have the best research evidence, Figure 1.1shows EIP residing in the shaded area, where practice decisions are made based on the intersection of the best evidence, practitioner's individual expertise, and client values and expectations. In discussing this diagram, Shlonsky and Gibbs (2004) observe:

None of the three core elements can stand alone; they work in concert by using practitioner skills to develop a client-sensitive case plan that utilizes interventions with a history of effectiveness. In the absence of relevant evidence, the other two elements are weighted more heavily, whereas in the presence of overwhelming evidence the best-evidence component might be weighted more heavily. (p. 138)

Figure 1.2represents a newer, more sophisticated diagram of the EIP model (Haynes et al., 2002). In this diagram, practitioner expertise is shown not to exist as a separate entity. Instead, it is based on and combines knowledge of the client's clinical state and circumstances, the client's preferences and actions, and the research evidence applicable to the client. As in the original model, the practitioner skillfully blends all of the elements at the intersection of all the circles, and practice decisions are made in collaboration with the client based on that intersection.

Figure 1.3is a multidisciplinary iteration of the three-circle model called the Transdisciplinary Model of EIP. This model was developed in a collaborative effort across allied health disciplines, including social work, psychology, medicine, nursing, public health (Satterfield et al., 2009). Figure 1.3retains elements of earlier EIP models; however, it also includes several changes that reflect the perspectives of the varied disciplines and practice contexts within which the EIP process is used. Practice decision making is placed at the center, rather than practitioner expertise, recognizing that decision making is a collaboration that could involve a team of practitioners as well as clients, whereby an individual practitioner's skills and knowledge inform but do not wholly describe the central decision-making process. Practitioner expertise is instead moved to one of the three circles and is conceptualized as resources. These resources include competence in executing interventions, conducting assessments, facilitating communication, and engaging in collaboration with clients and colleagues. Client-related factors, including characteristics, state, need, and preferences, are combined into one circle. The concept of a “client” is explicitly expanded to highlight communities in order to reflect the multiple levels of practice – from micro to macro levels and from individuals to large groups and systems – as reflected in the multiple disciplines. Finally, an additional circle is added to the outside of the interlocking circles to represent the context within which services are delivered in recognition of how the environment can impact the feasibility, acceptability, fidelity, and adaptation of practices in context.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Practitioner's Guide to Using Research for Evidence-Informed Practice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.