Michel de Montaigne - Essays

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michel de Montaigne - Essays» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Essays

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Essays: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Essays»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Essays: The Philosophy Classic

Essays: The Philosophy Classic

Essays — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Essays», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

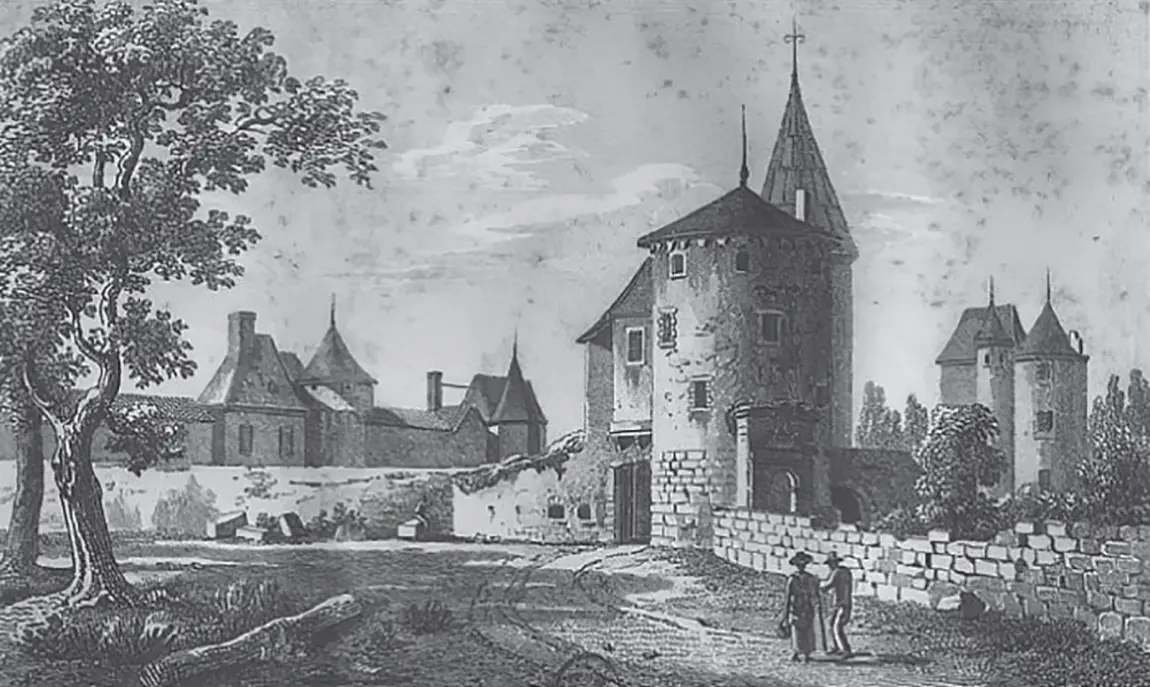

1568: father dies and he inherits family estate including chateau in Perigord. Works in a library in a circular tower above the estate buildings. Writes: “Miserable, to my mind, is the man who has no place in his house where he can be alone, where he can privately attend to his needs, where he can conceal himself!”

1569: publishes in Paris a French translation of Raymond Sebond's Theologia Naturalis.

1570: daughter Toinette is born. Dies three months later.

1571: daughter Léonor is born, the only one of several daughters to survive into adulthood.

1572–4: France is in civil war. Montaigne joins the royalist side and works on its behalf in Bordeaux.

1577: has his first attack of “the stone” – a hereditary kidney disease.

1580: the Essays are published. Montaigne presents a copy to Henry III.

1580–81: journeys around Europe, going from one spa to another seeking a cure. Has audience with Pope Gregory XIII. Recalled home when elected (against his will) mayor of Bordeaux, a position previously held by his father.

1582: second edition of the Essays published.

1583: heir to the throne Henry de Navarre visits Montaigne and stays in his chateau. Re-elected mayor of Bordeaux.

1588: third edition of the Essays published, including the new Book III. Arrested and taken to the Bastille as a hostage but released the same day.

1592: Montaigne dies. His wife and Marie de Gournay, a writer and translator who had become close to Montaigne, arrange for the publication of a final 1595 edition of the Essays.

1613: first English translation of the Essays published, by John Florio.

Château de Montaigne, by Jean-Jérôme Baugean, c. 1800, with Montaigne's tower in the foreground. It still exists as a Monument historique and can be visited.

Château de Montaigne, by Jean-Jérôme Baugean, c. 1800, with Montaigne's tower in the foreground. It still exists as a Monument historique and can be visited.

GUIDE TO THE CHAPTERS

BOOK I

On Idleness

When Montaigne retired from public life to his famous tower study on his estate, it did not turn out as he expected. Time on his hands did not lead to clarity of thought; rather, it made him more self-obsessed, melancholic, and prone to undisciplined imaginings.

On Liars

To lie well you need a good memory, which Montaigne distinctly lacks. In fact, his poor memory was a blessing in that he quickly forgot slights and could enjoy books he had read many times before. As humans are a species of word and speech, lying is the greatest vice, Montaigne argues.

That the Way We See Good and Evil Depends Upon the Opinion We Have of Them

Events are not good or bad in their own right, but our experience depends on how we perceive them. Montaigne agrees in principle, but chronic pain from his kidney stones and colic make it hard to live by these principles.

To Study Philosophy Is to Learn How To Die

A key part of Stoic philosophy was the premeditation or practicing of death so that it would not take us unawares. One should have perfect equanimity in the face of death or misfortune. Montaigne considers the vanity of humans who busy themselves and take on great projects as if they would live forever.

On the Power of Imagination

Mental impressions, ideas, thoughts, and fears have a hold on us, and it is often only by “sorcery” or tricks that we can loosen their power. Montaigne's example is sexual performance; he reveals old wedding-night customs designed to make things go well. Other examples of the power of thought and images include a woman who, having birthed a hairy child, blamed it on having a portrait of John the Baptist above her bed. Montaigne discounts history as being largely the work of the imagination; he is better at observing the present.

On Custom, and That We Should Not Easily Change an Established Law

The discovery of new worlds and peoples in Montaigne's time, plus the constant turmoil of political events in France and Europe, made him err on the side of custom or “rules of thumb”. What has been around for a long time has survived for good reason. “Novelty” is usually just some individual's idea of how things could change, often with negative social results.

On the Education of Children

In a chapter dedicated to his friend Diane de Foix (at the time, pregnant) Montaigne is full of quite modern ideas about how to bring up children, including teaching by inspiration rather than strong discipline. By analogy, kings and rulers should also act like a responsible and loving parent, instilling good values among their subjects.

On Friendship

“Friendship” here for Montaigne means bonds established in all kinds of relationships that are about the meeting of two souls (rather than just bodies). His model here is his deep friendship with Etienne de la Boétie, who had been accused of seditionary writings. Their loyalty to each other over time is analogous to a citizen who is loyal to the state.

On Moderation

Whatever pleasures humans find, they take things to excess, thereby making pleasure a vice. Even the study of philosophy, if engaged in too much, will make a person have contempt for religion and accepted laws and customs. “Everything in moderation”, and having respect for others, are a good rule for life.

On Cannibals

Montaigne is unusually open-minded for his time on the matter of “natives”. We only think them barbarous because they are so different to us in dress, beliefs, and customs. Western civilization has its own array of enterprises and customs which would look cruel and nonsensical to outsiders. Amid our hubris, we would do well to remember that the greatest “art” in the universe is nature itself.

On Solitude

Wherever we go, we take ourselves along. Montaigne sought freedom of mind and tranquility in his tower study, but found he was a prisoner of wandering, unhelpful thoughts. We do not need physical solitude as monks and nuns seek, but to be in the world and yet live with some level of detachment.

BOOK II

On the Inconstancy of Our Actions

Humans are full of contradictions, and mostly drift along with the flow of life without having a real plan. Our moods and affections change with the weather, and there's as much difference within us , as between individuals. Given that we allow chance to play such a part in our lives, it's no wonder that chance will dominate and take us places we'd rather not go.

Use Makes Perfect

Sometimes translated as “On Practice”, the practice in question is not mastering of a skill but preparing for death. Montaigne, like most people, feared death. That was until he was thrown off his horse in an accident and was concussed; from that moment he had more equanimity. Relating the incident leads to a discussion of how much one should talk about oneself. Not too much, he thinks, but never talking of oneself also goes against human nature.

On Books

Montaigne reveals his reading habits, noting that he will only keep reading a book he really enjoys; he feels the ancient books are more solid than recent ones; and he follows Horace's division of books into those that merely delight, and those that delight and are useful (particularly ones that help him be a better person). Among the poets, he ranks Virgil highest. Among the useful writers, he likes Plutarch and Seneca; Cicero is too wordy. Among historians, he finds most weak because they put narrative over fact.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Essays»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Essays» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Essays» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.