Genome Editing in Drug Discovery

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Genome Editing in Drug Discovery» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Genome Editing in Drug Discovery

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Genome Editing in Drug Discovery: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Genome Editing in Drug Discovery»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A practical guide for researchers and professionals applying genome editing techniques to drug discovery Genome Editing in Drug Discovery,

Genome Editing in Drug Discovery

Genome Editing in Drug Discovery

Genome Editing in Drug Discovery — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Genome Editing in Drug Discovery», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

21 Morgan, P., Brown, D.G., Lennard, S. et al. (2018). Impact of a five‐dimensional framework on R&D productivity at AstraZeneca. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17: 167–181.

22 Moscou, M.J. and Bogdanove, A.J. (2009). A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science 326: 1501.

23 Myhrvold, C., Freije, C.A., Gootenberg, J.S. et al. (2018). Field‐deployable viral diagnostics using CRISPR‐Cas13. Science 360: 444–448.

24 Rees, H.A. and Liu, D.R. (2018). Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19: 770–788.

25 Vamathevan, J., Clark, D., Czodrowski, P. et al. (2019). Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18: 463–477.

26 Wiedenheft, B., Sternberg, S.H., and Doudna, J.A. (2012). RNA‐guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 482: 331–338.

2 Historical Overview of Genome Editing from Bacteria to Higher Eukaryotes

Marcello Maresca

Genome Engineering, Discovery Sciences, BioPharmaceuticals R&D, AstraZeneca, Gothenburg, Sweden

2.1 Introduction

Molecular cloning methods have been instrumental for the establishment of the biotechnological industry. The ability to clone any DNA sequence of interest into a DNA vector has been a key technology advancement toward the generation of cellular and animal model of disease and the development of biopharmaceuticals. Traditional molecular cloning methods mostly rely on restriction enzymes‐mediated digestion and ligation of the digested fragments. Classical restriction enzymes recognize a relatively short DNA sequence and as a consequence, they are too unspecific to be used directly for DNA engineering applications in cellula .

Novel improvements in DNA assembly methods combined with the cost reduction and with the increase in accuracy of DNA synthesis processes have led to the possibility of assembling large DNA constructs in vitro . Synthetic genomes will have a key role in future DNA engineering platforms but they will not be discussed in this chapter and in this book, where we will focus on in cellula genome engineering approaches.

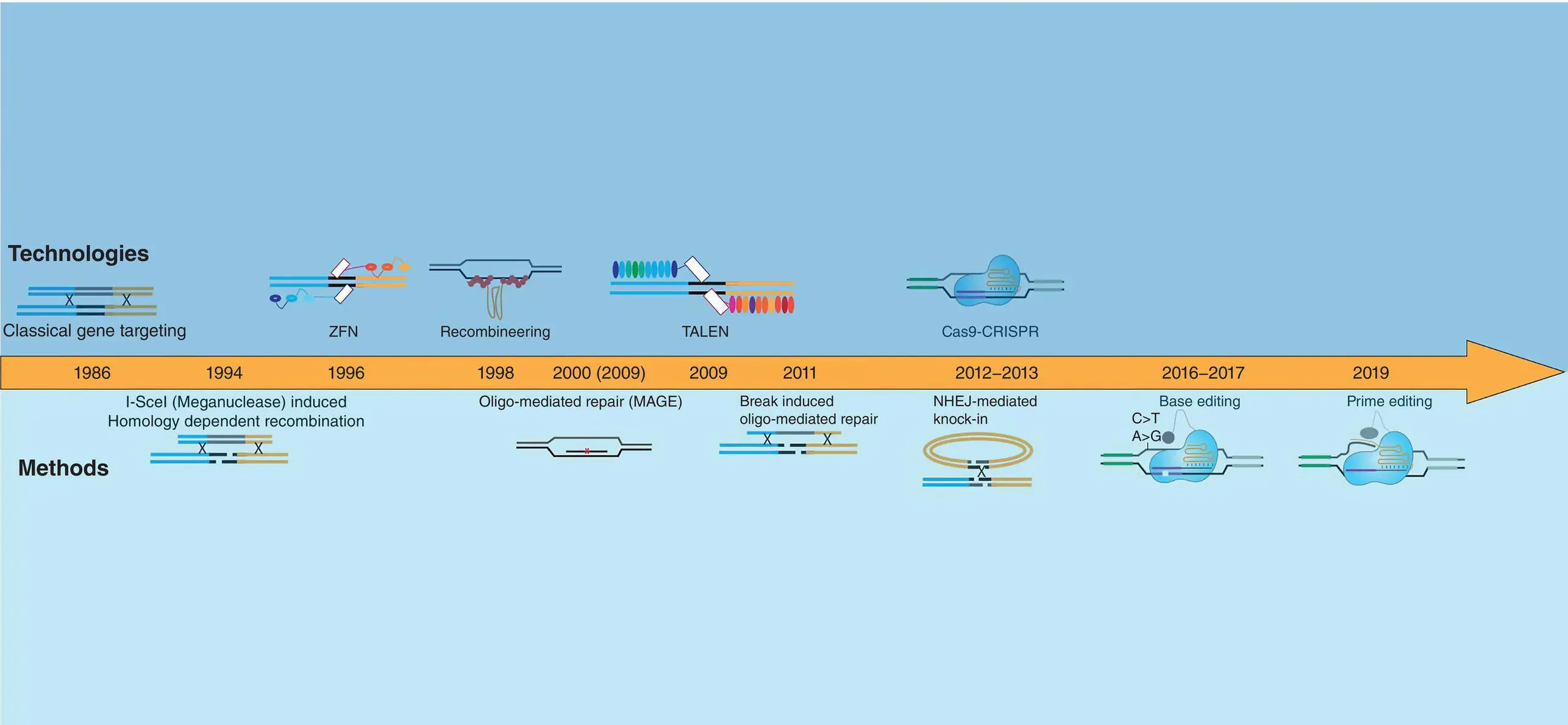

In this chapter, I will give a brief description of the advancements in the precise genome editing field starting from observations of single‐stranded oligonucleotides‐mediated repair in yeasts to Recombineering and CRISPR‐Cas9‐dependent editing. These technologies have all greatly expanded the tools and methods that are used to generate disease models and to develop assays for drug discovery ( Figure 2.1).

2.2 Bacterial DNA Engineering (Recombineering)

Microbes and microbial‐derived systems have been extensively used for the development of novel DNA engineering tools and for the application of these tools to DNA cloning. Restriction enzymes, recombinase systems such as CRE/Lox, integrases such as ΦC31‐Int, and the Cas9‐CRISPR system have all microbial origin. Recombinases and integrases‐based systems have been extensively used to engineer the mammalian genomes but we will not discuss them in this book that is focusing on scarless genome engineering systems. This chapter will focus on the development of Recombineering for bacterial engineering and its use in genome engineering with particular focus on applications in drug discovery.

The inspiration for the Recombineering ( recombination‐mediated DNA engineering) method came from studies in yeast where the possibility to introduce an exogenous DNA cassette in yeast genome was demonstrated in the years 1978–1979. Yeasts DNA recombination methods used homology arms to target a gene without the need of double‐strand breaks (DSBs) generation or the expression of any exogenous protein (Hinnen et al. 1978; Scherer and Davis 1979). It was also demonstrated in yeasts that single‐stranded oligonucleotides with short homology arms to a target sequence are able to promote genomic insertions/deletions/modifications (Bhargava et al. 1999) Unfortunately, this approach does not work efficiently in wild‐type bacteria or in higher eukaryotes. This has limited the utility of single‐strand oligonucleotides‐mediated DNA editing of bacterial and mammalian genomes before the advent of recombineering. Murphy´s and Stewart´s groups showed for the first time that a portable recombination system can be introduced in Escherichia coli to induce recombination in bacteria in a similar fashion to the yeast recombination system but with much higher efficiency (Murphy 1998; Zhang et al. 1998). The portable cassette encodes for an exonuclease (i.e. Redα for the lambda Red system), a DNA annealing protein (i.e. Redβ), and the RecBCD inhibitor (i.e. Redγ). In particular, Stewart´s group showed that this system works with very short homology arms (as short as 30nt) via a peculiar mechanism of single‐strand heteroduplex intermediates at the replication fork (Maresca et al. 2010). This observation paved the way to the use of Recombineering for Precise Genome Editing of Bacterial Genome and for molecular cloning strategies. Recombineering overcomes the limitation of classical restriction/ligation‐based cloning because it does not require the availability of unique restriction sites in the target plasmid and it is specific enough to target the bacterial genome. Therefore, Recombineering has been extensively used for the seamless engineering of large constructs such as bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) and for the engineering of bacterial genome.

Figure 2.1 Graphical overview of genome engineering technologies (upper panel) and methods (lower panel) developed during the latest 27 years. A schematic representation of the different technologies or methods is presented, respectively, above or under the timeline arrow.

2.3 BAC Recombineering

The use of recombineering has been particularly important for functional genomics programmes where BAC transgenes or Gene Targeting constructs have been engineered at large scale to generate animal models of disease or to develop libraries of gene tagging. The European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis (EUCOMM) and Knock‐Out Mouse Programme (KOMP) contributed to the large‐scale generation of conditional gene KO mice that have been extensively used in Drug Discovery. In particular, Skarnes and colleagues developed a large conditional knock‐out mouse library in the framework of the EUCOMM programme by using a high‐throughput gene‐targeting pipeline based on Recombineering (Skarnes et al. 2011). This gene‐targeting pipeline has been greatly facilitated by the development of a high‐throughput strategy of DNA engineering where “recombineered” targeting constructs were used to engineer C57BL/6N mouse embryonic stem cell for the generation of KO mice. This mouse library has been instrumental to understand the function of genes encoded by the mammalian genomes ( In vivo ) and to validate drug targets.

Another particular relevant example of Recombineering applications in Drug Discovery/Development is the remarkable work by scientists at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals aimed to engineer a humanized mouse model producing human–mouse hybrid antibodies. Their VelociGene platform (Murphy 1998) allowed the generation of multiple knock‐out/knock‐in by an high‐throughput recombineering & gene targeting approach where “recombineered” BACs are inserted in mESC using sequential homologous recombination steps. This led to the replacement of mouse immune genes with human orthologs (Valenzuela et al. 2003).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Genome Editing in Drug Discovery»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Genome Editing in Drug Discovery» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Genome Editing in Drug Discovery» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.