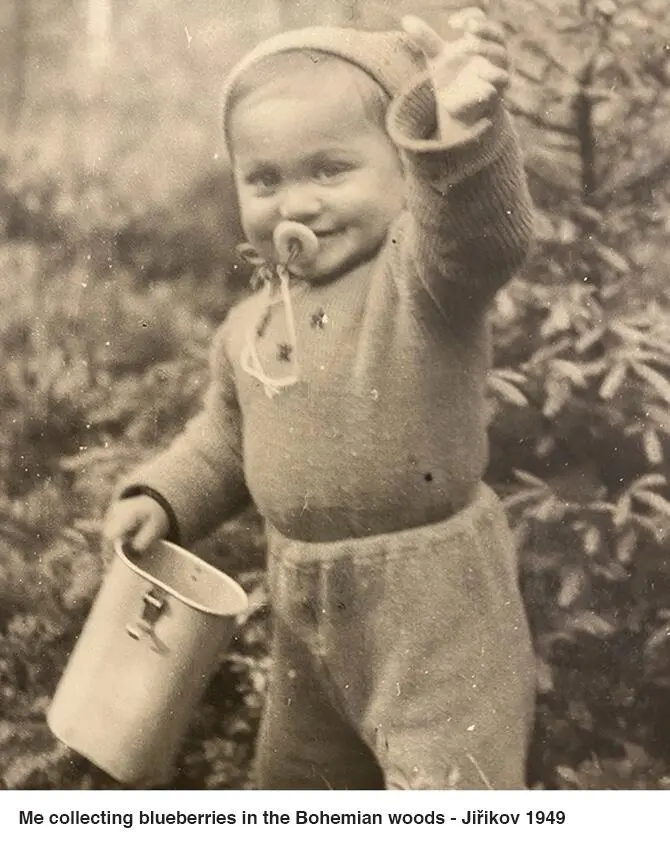

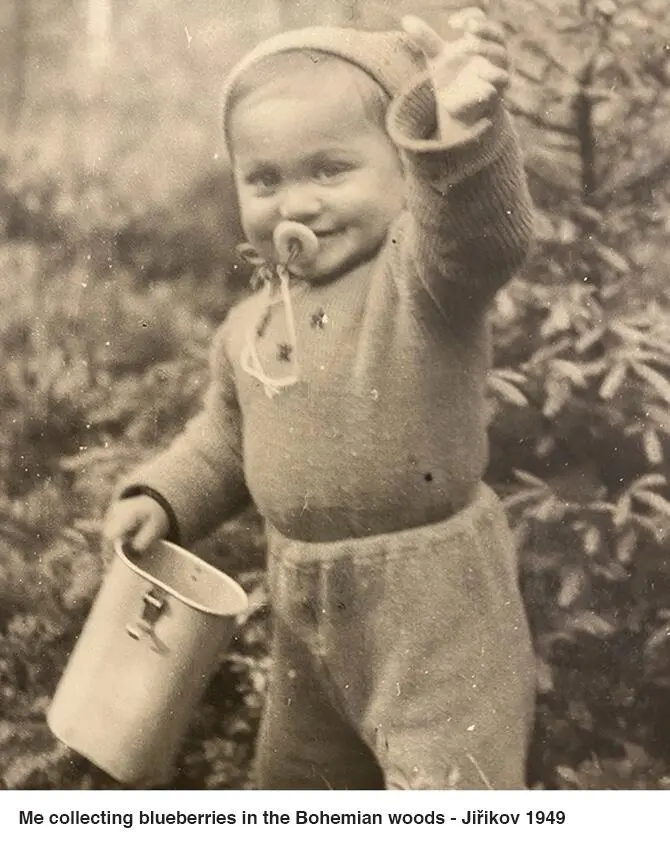

Amongst my happy, garden memories, I can still picture the large, fenced plot where my mother grew most of our fruit and vegetables, and where she also cultivated flowers for the house. Summers were quite short, so strawberries, gooseberries and redcurrants were all grown to ripen rapidly. Needless to say, having acquired an early passion for blueberries, I had to be restrained from eating all the garden fruit myself! The beds of poppies I remember particularly, with their bright, fragile blooms, waving gently in the breeze. Their fragrance was stunning and, to me, they looked very beautiful too, though my mother grew them primarily for the seeds that are such an important ingredient in traditional Czech cuisine. Since that time, and throughout all my years, I have always retained a love of poppies.

The less romantic amongst the readers of this memoir might dismiss the above descriptions as mere trivial sketches from a privileged, over-indulged, almost fairy-tale childhood and they would, at least in part, be right. But sadly, as we grown-ups all know, where there is light, there are shadows too, and the brighter that light, the deeper and darker the shadows become. And during those years, there were shadows growing all around us.

I was much too young at the time to understand the struggles my parents were grappling with, but I did have a definite sense that not all was well, that they were fending off some kind of storm, coping every day with circumstances that worried them both and made them unhappy. Clearly, good parents will always seek to protect their children from anything that is dangerous, unpleasant or distasteful and, with painstaking care, my parents endeavoured to shield me from their fears and give me as normal a childhood as possible. But I shall not forget the people in uniform who used to make regular visits to our house and, almost without exception, the loud exchanges that ensued between them and my father, exchanges that would reverberate frighteningly from the library throughout the entire house. After such visits, my father was nearly always in a rage and my mother’s disconsolate expression would betray her own deep concerns. I had not the least idea about what was happening, of course, but even I could discern that these visitors were never the bearers of glad tidings. Oddly, what has stuck in my mind particularly is that I never recall a single one of them smiling, ever, at anybody, not even at cute little me, so, in my childish imaginings, I associated people in uniform with Bad Things.

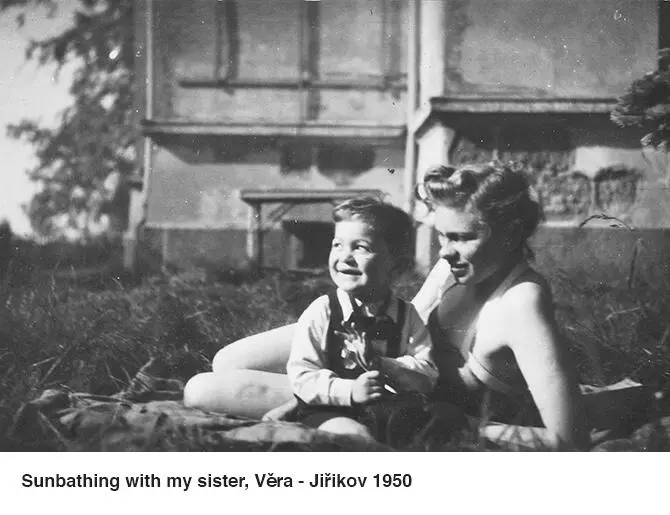

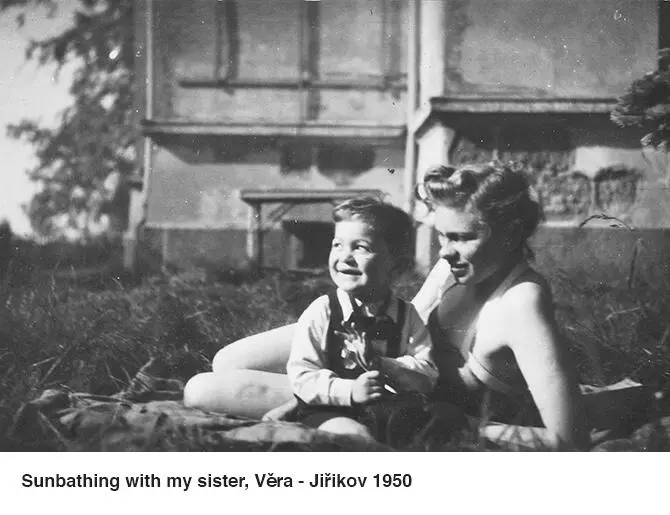

Apart from weekend visits by my grown-up brother and sister - they were both much older than me and no longer lived at home - mine was a rather solitary existence; hardly anyone ever visited our house, apart from the nasty folk in uniform. Some years later, I discovered to my surprise that most children normally played with other children, but no children ever came to play with me. What I didn’t quite realise at the time was that no-one could; no other child was permitted to come. But during those early years, I suppose that I could not have missed what I had never experienced and so, to be entirely frank, I confess I have retained only happy memories from that period of my life.

CHAPTER 3

OF NUNS, RABBITS AND RAILWAY TRAINS

At that time, there must have been a convent nearby because, once a week, a group of nuns, dressed in the flowing, sombre habits of those days, would walk past our house on their way to the local church. Watching them through our iron gates, I was fascinated by these strange beings. One day they caught sight of me and stopped; they asked me a few questions about my name and age and suchlike - the sort of questions adults always put to small children they don’t know - and, as I responded, they looked at me in what I felt was a kind and friendly way - several of them even smiled at me. I didn’t see many people passing by like this, close to our house, and even when they did, they most assuredly did not smile; they usually turned and looked away. The nuns were completely different: they might all have been draped, head to foot, in black habits and pure white wimples, but they almost seemed to radiate goodness and light. One Sunday, seeing them make their usual weekly progress towards the house, I ran out to meet them; to my great surprise and delight, they passed through the gate to me a little parcel of what proved to contain vanilla crescent biscuits (Vanilkové rohlíčky) - in English, they are called ‘Viennese Fingers’. The smell of vanilla was wonderfully exotic and the taste of the soft, sweet, crumbly hazelnut pastry I shall never forget. (I still have a soft spot for these particular biscuits!) Anyway, I was in heaven.

After that, every week, when the sisters came past our house, they would always slip me the same little parcel of deliciousness - they must have made them fresh every week. But nothing lasts: one week, to my bitter disappointment, they failed to make their customary visit and I was heartbroken; I never saw them again. Many years later, I learned that the convent had been dismantled by the state and who knows what happened to the sisters. I hope they were safe and were able to keep on making Vanilkové rohlíčky for many more years. Religion was to play no part in the building of a bright, Socialist future, of course, but I for one will never forget the kindness of these nuns, their smiling faces and their tender touches through the garden gate. Even more, I shall never forget the delicious biscuits they brought me every week. Was I not a lucky little boy?

Despite my gifts of scrumptious biscuits, I gradually became aware that my parents were having difficulty obtaining certain foodstuffs, though I wasn’t sure exactly why. Luckily, my mother grew most of our vegetables herself, together with some fruit; she also kept rabbits in the basement, not as pets, of course, but as our only source of fresh meat. At one time though, we did have one of these large, tame rabbits living with us in the house, and he was definitely a family pet. He was big and beautiful. I loved to stroke his gorgeous, soft fur and to feed him carrots, which he consumed with amazing gusto. I think his name was Bimbo and my brother, Mirko, adored him. Whenever Mirko came to the house, Bimbo would bounce on to his lap, where he would settle happily, occasionally managing to chew off completely one of the buttons on Mirko’s shirt. If Mirko found this amusing, my mother was not pleased at all. Bimbo was certainly no saint: he loved to chew through anything that looked interesting and vaguely edible, so no shoelace was safe from his voracious appetite and his destructive incisors. His nemesis came on the day he succeeded in gnawing his way through an electric cable; my mother finally lost patience at this wanton destruction and decided that Bimbo’s end was definitely nigh. His fate was to come in the form of a ‘Bimbo stew’, a delicious, heartwarming dish much enjoyed by everyone around the table, in blissful ignorance of its grim ingredients. Searching for Bimbo some time later, my brother discovered the terrible truth about his beloved Bimbo’s end; he refused to speak to our mother for weeks afterwards. No mention was ever made of Bimbo thereafter, but I don’t think my brother ever quite forgave my mother for the slaughter of his darling rabbit.

Читать дальше