Traditional and modern instruments

Stages in the construction of the Morin Khuur.

The master craftsman in his workshop.

In front of his workshop, in the town’s jurte settlement.

The legend: “Khukhuu Namjil“

Many years ago, a young man named Khukhuu Namjil lived in the east of the country. He was known far and wide as an excellent singer. One day, a long way from home, he was letting his horse graze on the banks of a river when a young, enchanting girl rode out of the waters towards him. She spoke to him and persuaded him to ride with her to her parents. He stayed there for several days and entertained the family with his singing. It didn’t take long until it the decision was made that the young couple should marry.

Even though the young man was happy in his new family, after a while he was drawn back to his own family, particularly to his truelove who he had left behind there. Between them, they agreed that he should split his time between the two families and the girl allowed Khukhuu Namjil to leave, giving him a fawn-coloured horse for the journey. With this horse, he would be able to ride each day to be with his wife and family but then at night, he could return to his original family and truelove. He must however ensure that the horse should be allowed to stop at a reasonable distance before the man reached his own jurte so that it would have a chance to recover its breath.

He headed off on his fawn-coloured horse. For three years, he spent his days with his wife and family but at night, he returned to his far-away truelove. Then one day, when he forgot to give his horse time to rest before getting home, his wife became suspicious and taking a pair of scissors, she killed the horse by stabbing it.

For three long months, despairing at not being able to get back to his truelove, Khukhuu Namjil ate nothing. Finally, he carved a likeness of the head of his dead horse from one of its bones and made himself a fiddle that he strung using horse hairs. From that day on, he accompanied himself on that fiddle as he sung his sad and mournful songs.

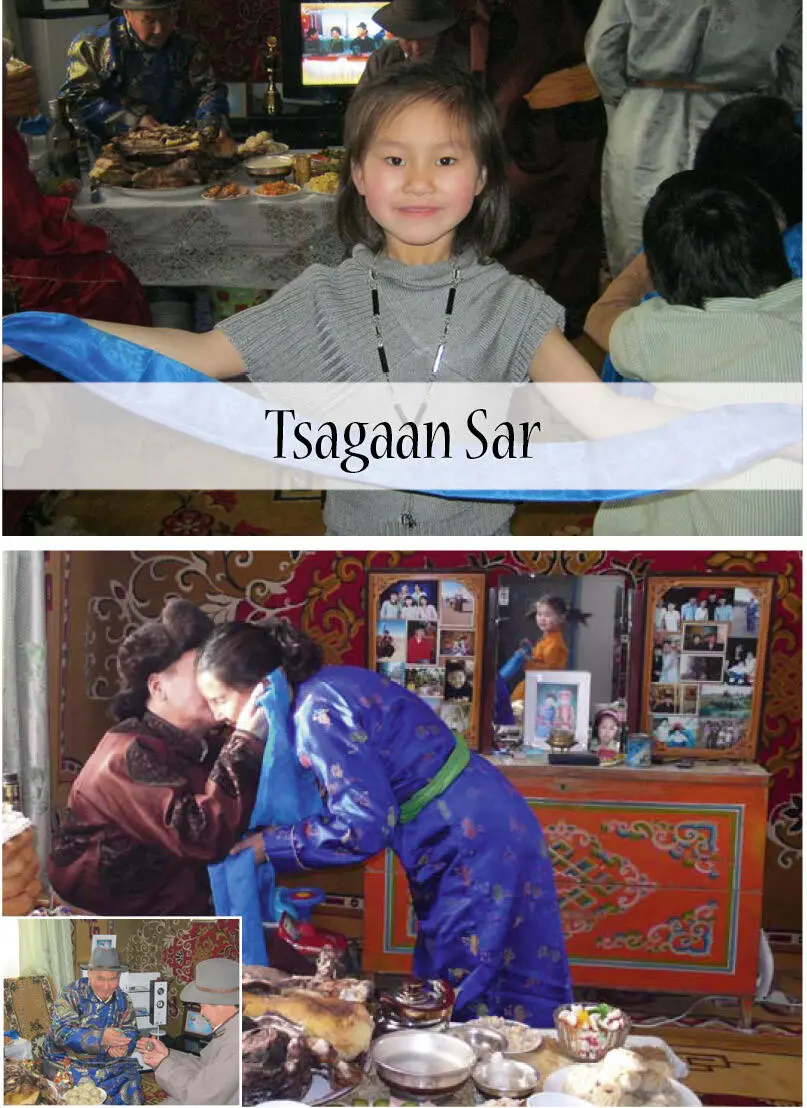

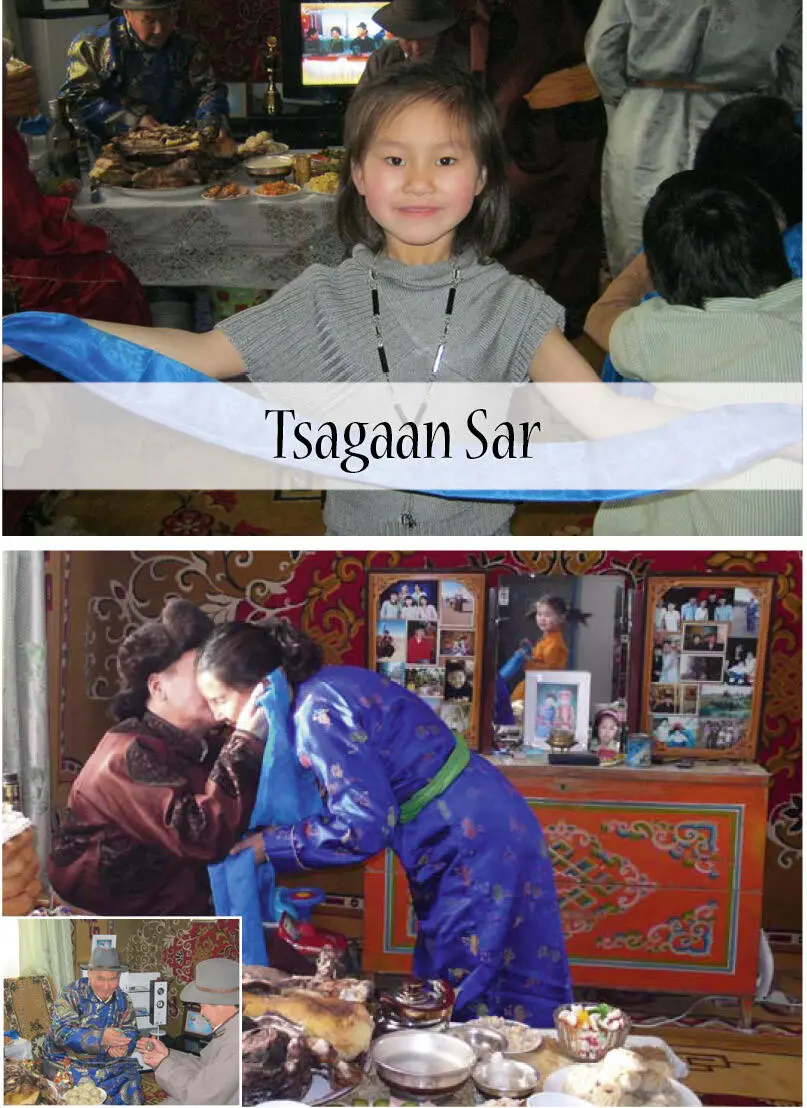

Tomorrow is Tsagaan Sar, the Mongolian New Year Festival. Throughout the whole day, I have the sense of the pre-Christmas atmosphere that we have back in Germany. People scurry about the squares and streets with bulging shopping bags as if they are afraid that soon there will be nothing left on the shelves. I am pushed here and there in the crowd. I am waiting at the bus stop in Sukhbaatar Square. I wait a while for the bus to turn up and then I decide on a different option. I call Saulegul who in the same way as I am, is also on his own at holiday times. The Kazakhstanis, who like Saule are of the Moslem faith, do not celebrate this Buddhist festival. We arrange to meet that evening in a pub.

The Mongolian New Year is a moveable feast that takes place on different dates from the end of January to the end of February. The lamas from the largest monastery in Ulaanbaatar, Gandan, determine the exact date of the festival each year. They calculate it based on the first phase of the new moon and the Asian calendar.

Back in the year 1206, Chinggis Khaan decreed that the start of spring should be celebrated each year as this is the time when the animals give birth to their young. This start of the new cycle of life should be marked by the people through celebrations. The name White New Year Festival is derived from the colour of milk. In the 17th century, Zanabazar, as the first Bogd Khaan and in his capacity as the head of the lamas, absorbed the previously secular festival into Buddhism, which had recently been introduced. Also the tradition of including a further fifteen days goes back to him, as this is the period during which Buddha was reborn.

Starting from the day before the holy festival and going on into the first morning, ceremonies are held in the monasteries and homage is paid to the two deities Bandanlkham and Lkham. During this night, Lkham is said to travel through three thousand worlds and is believed to visit every Mongolian family. For that reason, Tsagaan Sar is also a family festival where, according to the ancient practice, family members meet on the evening before and pray for divine support during the year ahead.

The traditional meal to accompany the festival consists of three, five, seven or nine layers of Kheviin Boov, a light, sweet pastry, shaped into a pyramid and served with buuz, Mongolian dumplings filled with meat. There is also uuts, steamed mutton or uvchuu, steamed beef. Various salads accompany this. Airag, fermented milk, tsagaan arkhi, milk schnapps and suutei tsai, milk tea, are served as drinks. Aaruul, a type of cheese eaten throughout Central Asia and sugar are placed on the frame around the door to the jurte on the eve of the festival. In the towns, this tradition is replaced by placing gifts on the door step or if available, on a balcony rail. This gift is seen symbolically as food for Lkham’s mule.

That evening, there are not many other passengers on the bus, which is a new experience for me. Normally, all the municipal buses are full to overflowing at all times of the day. Most of the locals live in tower blocks and tenements outside the centre of town or in the jurte settlements. By now, they will be there, complete with their purchases. This evening, the celebrations are keeping the people indoors. There is no traffic driving into the city. The streets of the great metropolis are empty of people and I feel like I am being driven through a ghost town. Will any pub or bar be open this evening?

Saule’s directions are good. I spot the bar from a distance, nestling between the modern-style houses. I sit at one of the attractively decorated tables, order a Chinggis beer and wait. Saule arrives, unusually punctual and for a while, we are the only customers. Slowly, the bar, which is one of the most popular in town, starts to fill up. However, there are no Mongolians to be seen. It just appears to be Americans and Europeans, business people who for the most part are working here.

Later on, a Mongolian father and his small son enter the bar. They sit at the table next to us and order two meals. The father looks sadly at the little boy who silently flicks through a small book. On this, a family holiday, they prefer the companionship of a bar to the loneliness of their two room flat.

Читать дальше