Matthias Bernt - The Commodification Gap

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Matthias Bernt - The Commodification Gap» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Commodification Gap

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Commodification Gap: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Commodification Gap»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

—Jennifer Robinson, Professor of Human Geography, University College London, UK

—Manuel B. Aalbers, Division of Geography & Tourism, KU Leuven, Belgium The Commodity Gap

The Commodification Gap

The Commodification Gap

The Commodification Gap — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Commodification Gap», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

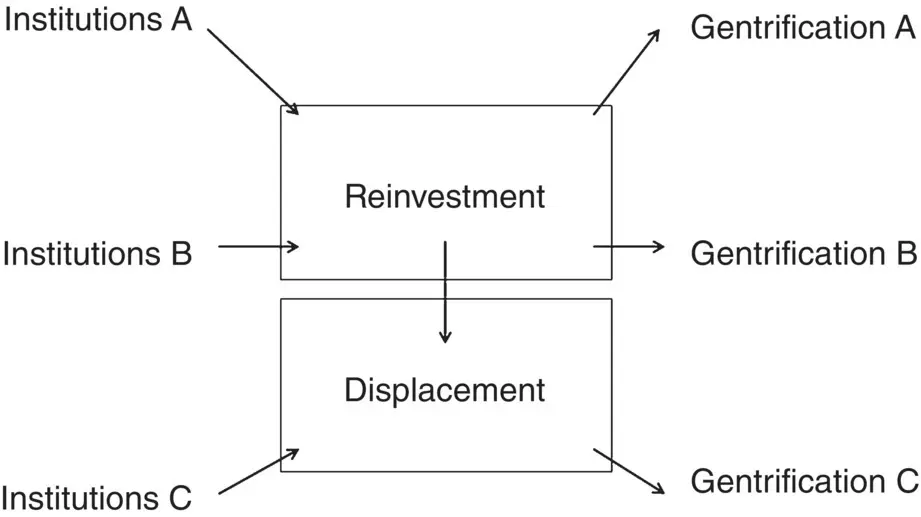

FIGURE 1.3 The relation of institutions, reinvestment, displacement and gentrification.

Having manifold representations of gentrification in mind, I focused on inner city residential neighbourhood change. I thus went to the ‘usual suspects’ of gentrification. The reason for this is that I aimed to include urban environments that would be connected to gentrification by most observers. Moreover, two of the cases selected have a longer history, allowing us to study the impact of changing institutions and regulatory environments over time. Typically, such cases are to be found in inner city environments. Based on these considerations, I selected Barnsbury (London) and Prenzlauer Berg (Berlin) as case studies. Both these neighbourhoods are seen as classical cases in their contexts and have been gentrified over decades. Case selection was more difficult in Russia, as gentrification is a new phenomenon there and often seen as a matter of newly built gated communities on city fringes or in former industrial wastelands, rather than as an inner city phenomenon. Nevertheless, I studied gentrification in the ‘classical’ environment provided by St Petersburg’s inner city (Tsentralnyi Rayon). While this might be seen as being prone to the fallacy of morphological determinism, I argue that it is exactly the difficulties that gentrification faces in these environments that provide lessons to be learned. In some respects, the case of St Petersburg can be regarded as a control case, allowing insights that cannot be gained in Germany or the UK.

Why did I study gentrification in Russia, the UK and Germany as opposed to, say China, Nigeria and France? There are two reasons for this. First, on an epistemological level, while all these countries are located in Europe, they have very different histories and state structures, resulting in different relationships between capital, state, land and the people. Despite morphological similarities, they present different sets of institutions, relations and practices. As the study focuses on causality, not regularity or generalisability, choosing other cases would have allowed including even more dissimilar cases, making it possible to find other causalities. However, this would hardly have resulted in substantial changes with regard to the general theoretical argument put forward. As Jennifer Robinson has argued, comparison can start from ‘anywhere’ (2016) and there is no privileged position of one potential case against the other. Second, there are practical issues. Analysing the relationship between gentrification and public policies on an in‐depth basis in different countries demands the researcher have the capacity to read local literature, analyse planning documents and legislations, and conduct interviews. 5 Furthermore, background knowledge on history, culture and social structures is helpful, to say the least. As German, Russian and English are the only three languages I speak to a degree that allows for this kind of work and as I didn’t have the resources to hire a team of researchers, the selection of cases has been influenced by my personal background. I also have known all three cities for a long time, which made it easier to build upon existing contacts and obtain access to various sources of information.

With regard to data and sources, the research strategy has been different for all three cases studied.

In this respect, London is the birthplace of gentrification as a concept and arguably one of the top sites covered by urban studies worldwide. When trying to understand the constellations here, I was able to draw on an expansive and varied literature. Moreover, due to the concentration of academic institutions in London, I profited enormously from the background knowledge and advice provided by fellow researchers who have studied London for decades. I also interviewed a limited number of experts on the neighbourhood I researched, including real estate managers and planners. In addition, compared with Germany and Russia, the range and the quality of statistical data is excellent and the data was accessible.

My research on Prenzlauer Berg differs from this. Prenzlauer Berg is not only the place I have lived in for most of the last 30 years, but it is also a neighbourhood that I have studied intensively since I became an academic. As a consequence, most of the data and much of the interpretation included in this book are based on past work that I have brought together and updated for this study. Methods used here include a literature review, the analysis of public planning documents, interviews and participant observation in numerous events, meetings and public hearings over the last three decades.

St Petersburg has been a completely different affair. The term gentrification has hardly made it to Russia thus far, and the number of studies on this phenomenon is very small. Moreover, in Russia, the transition from socialism to capitalism has resulted in taking away resources from the academic system to such a degree that urban research is generally fairly weak (when compared with the West). The staggering lack of resources has also contributed to isolating many Russian scholars from discussions in the West and this has been changing only very recently. Moreover, official statistics are notoriously unreliable in Russia. In order to grasp the dynamics under which gentrification operates there, I therefore had to do primary research. In this, I was supported by Russian colleagues who were enthusiastic about the issue and willing to invest their time and intellectual resources. Together with them, I organised a Research Laboratory in 2015 at which we discussed the applicability of Western literature to the Russian situation and performed empirical research in two neighbourhoods destined for larger urban renewal projects in St Petersburg. We applied a mix of document analysis, expert talks and intensive site inspections accompanied by interviews with residents to obtain an understanding of the actual developments on the ground. For a number of reasons, this work was never finished – yet it provided invaluable insights that helped me to understand the specificities of the situation there.

I proceed as follows: having sketched my approach in the previous pages, Chapter 2re‐examines the rent gap. Its task is to recapitulate the central features of this theory, as well as to discuss its limitations. Doing so, I try to avoid ‘the booby trap of the stalemate between “production” versus “consumption” explanations’ (Slater 2017, p. 121) that has occupied gentrification research for a long time (for summaries of these debates see Lees et al. 2008; Brown‐Saracino 2010). I find that the arguments brought forward in this debate have reached a point of saturation where conceptual progress becomes unlikely and I aim at new lines of questioning. The main message I develop in this chapter is that the rent gap theory is indispensable for explaining gentrification, but too abstract and oversimplifying. I discuss five major problems in this context that point to the limits of this theory. These are: a lack of attention towards barriers to capital flows; the problematique of connecting the scales at which potential and actual ground rents are produced; the implications of a nomothetic conceptualisation of land rent; the limitations of a unidirectional understanding of property relations as ‘control’; and turning a blind eye towards the actual conditions for the realisation of rent increases and the role that the state plays in this. On this basis, Chapter 3provides a first look into the institutional parameters that frame the operation of gentrification. It analyses the different housing systems in the UK, Germany and Russia through a historical perspective that highlights the strategies, ideologies and struggles that have shaped the design of the diverse institutions at different points of time and discusses the implications of these for the operation of the rent gap. Taking a long‐term perspective, I focus on the changing conditions for reinvestment in the housing stock, roles of tenures and rent laws, and identify 12 commodification gaps (see Table 3.6) relevant for the operation of gentrification in the UK, Germany and Russia at different times. Together, these gaps guide the analysis of the cases on the neighbourhood level that follows and are further refined through empirical examination. Chapters 4– 6apply this framework to the neighbourhood level and examine the operation of gentrification in the neighbourhoods of Barnsbury (London), Prenzlauer Berg (Berlin) and the centre of St Petersburg (Russia). Finally, Chapter 7discusses the implications of this analysis for the theorisation of gentrification. It revisits the main themes, discusses the findings of the empirical observations and suggests a reconceptualisation of gentrification. It refines the commodification gap as a new theoretical concept and argues for a reorientation of gentrification studies.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Commodification Gap»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Commodification Gap» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Commodification Gap» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.