Internal Below‐the‐Surface Obstacles

The leader brings a complex stew of emotions, experiences, identities, beliefs, values, motives, and character traits that have a much larger impact on the leader's competency level than what we are aware of above the surface. If the leader's below‐the‐surface characteristics do not align with their above‐the‐surface knowledge, skills, and intended behaviors, then it is not likely they will be able to “perform.”

We can teach to the above‐the‐surface competency gaps by practicing skills and building knowledge. Sometimes skill building is all a leader needs to become competent. This is often the case with leaders who are new to a competency. These leaders find that new knowledge and skills fit nicely with their existing beliefs, motives, values, etc. Through practice, they grow quickly.

Unfortunately, we cannot teach to the below‐the‐surface competency gaps. If there is misalignment between skills, knowledge, and behaviors and a person's values, beliefs, identities, motives, and character traits, there is no amount of teaching that will change that. No one can teach us to shift these deeply personal aspects of ourselves. Others can support us to make those shifts, but the new awareness and strategies come from within ourselves.

Interpersonal Below‐the‐Surface Obstacles

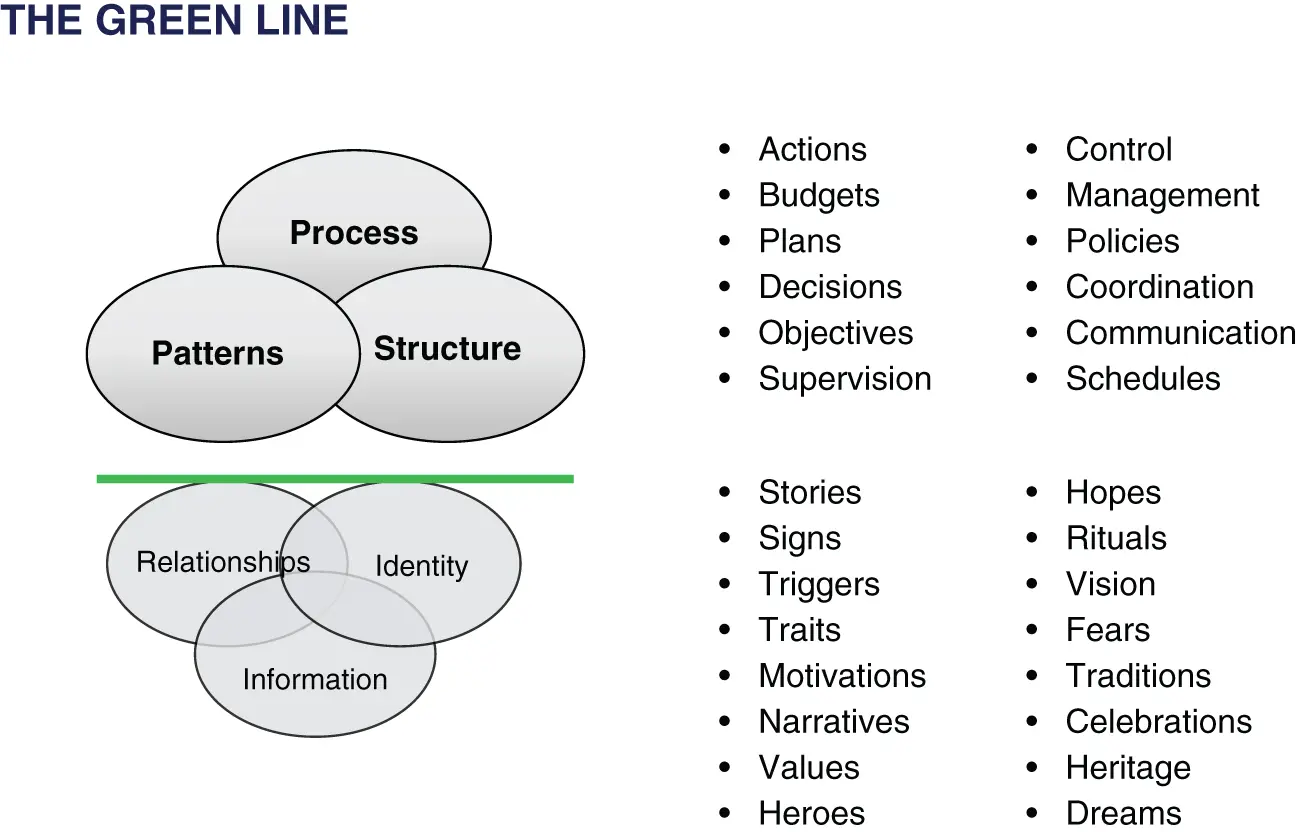

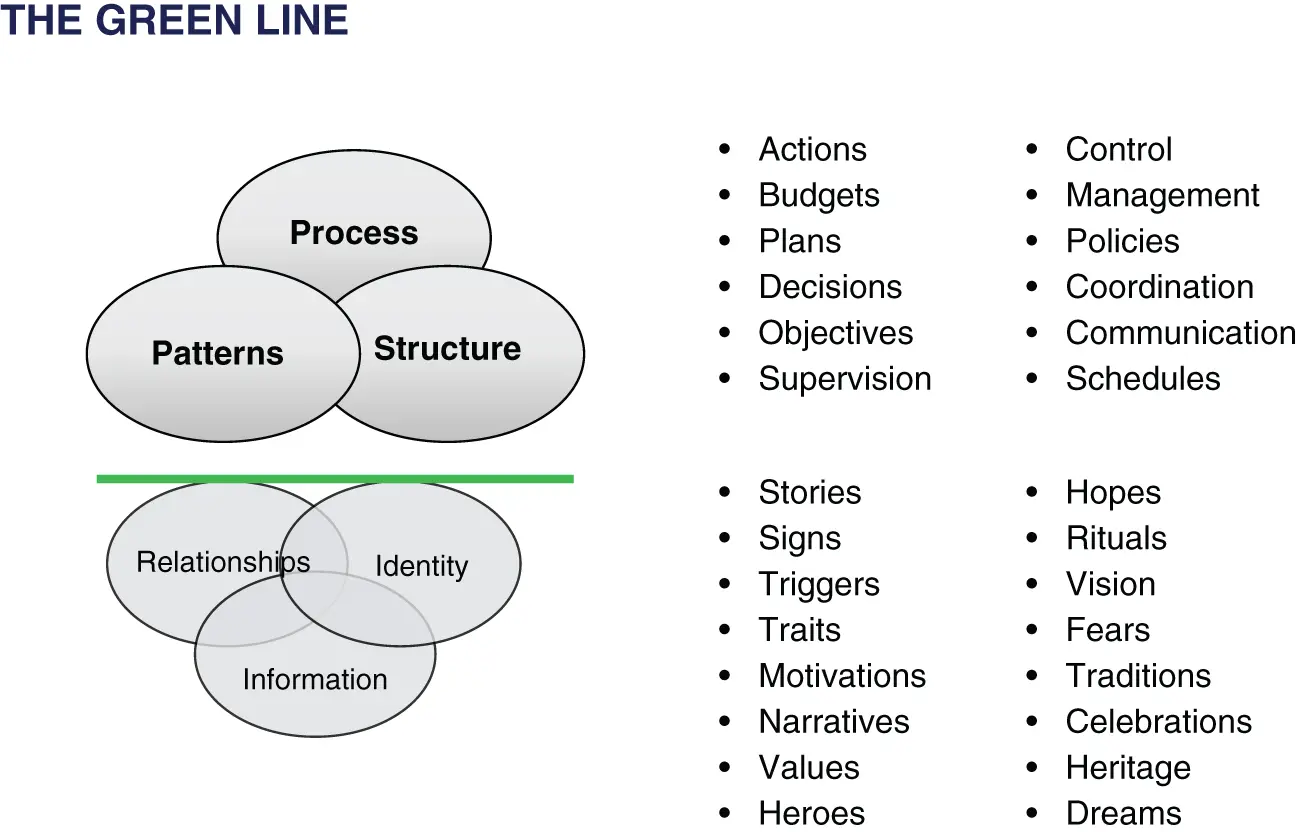

What is invisible below the surface between leaders and the people they lead also contributes to self‐limiting mindsets. In her Six Circle Model, leadership consultant Margaret Wheatly created the simple but powerful concept of the Green Line to illustrate this social version of the below‐the‐surface concept (Perrius 2014). 15 The three circles above the Green Line (the horizontal line in Figure 1.2) embody the conversation we tend to focus on with our stakeholders, in essence, what's on the agenda. The three circles below the Green Line represent another entirely different, potentially high‐stakes level of interaction that may go unnoticed and unaddressed. This interaction is emotional and personal. It is the interaction of identities, values, assumptions, emotions, histories, and more. What is happening below the Green Line is always in the room, whether we are aware of it and engage with it or not.

Figure 1.2: Wheatley's graphic illustration of the Green Line concept.

Source: Margaret Wheatly, 1992.

Strong leaders value what is happening below the Green Line and they are adept at surfacing this material, and then engaging with it. Part of this strength is skill, and part of it is mindset. We can't teach this essential leadership mindset just by telling leaders what others are experiencing and having them read books, though these can be part of the solution. Leaders must shift their value systems and learn to exercise new muscles like empathy and compassion to do this well.

… But Productive Mindsets Can Be Learned

We cannot teach below‐the‐surface competencies, but they can be learned. More aptly put, people can change deeply engrained habits of mind and behavior that often seem like permanent aspects of who they are.

Neuroscientists have discovered that our habits of mind and behavior become encoded in our brains as neural pathways. The deeper the habit, the stronger the neural pathway. Our oldest and deepest habits are neural superhighways that are very easy for us to travel. We follow them almost automatically when they are triggered by our environment, our emotions, and our thoughts. The exciting news about neural pathways is that we can deconstruct and replace them with new neural pathways through intentional focus and practice. We can intentionally rewire our brains! (Goleman, Boyatzis, and McKee 2001). 16

Not surprisingly, rewiring our brains takes significant effort and time. New pathways start out as footpaths that we carve with a machete in the wilderness, even as we long for the comfortable old neural superhighway of habits in the distance. We have to carve the new path over and over again for it to evolve—and stick. We must face the triggers of old habits and force ourselves to choose a new behavior over and over again. Over time, the paths become wider and easier to travel, and our old pathways begin to shrink. When we are successful, the new habit becomes the superhighway and the old one becomes the small dirt path in the forest.

Emotional Intelligence leadership theory, when applied effectively, provides a method to support leaders to rewire our brains, and overcome our deepest self‐limiting mindsets. We cannot teach ourselves out of the seven self‐limiting mindsets discussed earlier in the chapter, but we can build new mindsets and internal habits with a deliberate focus on self‐awareness and self‐management. Once we are aware of our “stuff,” we can build self‐management strategies that will help us to construct new neural pathways. As we begin to shift our internal patterns of thinking and behaving, we draw in social awareness to help us make changes in how we see the world. The self‐work inevitably leads to acquiring a new perspective about others. Productive new leadership behaviors are the inevitable culmination of this type of deep, internal work.

The next chapter will ground you in EI theory and our 5‐Square method for supporting leaders to shift their mindsets and behaviors. The foundational concepts are Goleman's, but we have made them operational in our 5‐Square. Once you understand how the 5‐Square supports personal leadership transformation, you will be ready to begin the personal leadership work of this book.

1 1.McCleskey, J.A. (2014). Situational, transformational, and transactional leadership and leadership development. Journal of Business Studies Quarterly 5(4), 6–9.; Spahr, P. (November 25, 2014). What is Transactional Leadership? How Structure Leads to Results. Retrieved November 8, 2016, from http://online.stu.edu/transactional-leadership/ (accessed 18 November 2016); Hargis, M.B., Wyatt, J.D., and Piotrowski, C. (2011). Developing leaders: Examining the role of transactional and transformational leadership across contexts business. Organization Development Journal 29 (3): 51–66.

2 2.Heath, C. and Heath, D. (2010). Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. New York: Random House.

3 3.CT3 Web Admin (2018). A powerful paradigm shift for educators. https://www.ct3education.com/2018/05/08/a-powerful-paradigm-shift-for-educators/.

4 4.Ibid.

5 5.Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., and McKee, A. (2002). Primal leadership: Learning to Lead with Emotional Intelligence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

6 6.Charan, R., Drotter, S., and Noel, J. (2011). The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership Powered Company, Second Edition. San Francisco: Wiley; Batista, E. (2013). Doing less, leading more. Harvard Business Review https://hbr.org/2013/12/doing-less-leading-more.

7 7.Mount, P. and Tardanico, S. (2014). Beating the impostor phenomenon. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership; Mount, P. (2015). Impostor phenomenon. Training Journal, 5(8).

8 8.Boyatzis, R. and McKee, A. (2005). Resonant Leadership: Renewing Yourself and Connecting with Others Through Mindfulness, Hope, and Compassion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

9 9.Zone of proximal development. (2009). Penguin Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved from Credo Reference database Affective Domain.

10 10.Bloom, B.S. (Ed.), Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H. et al. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc.

Читать дальше