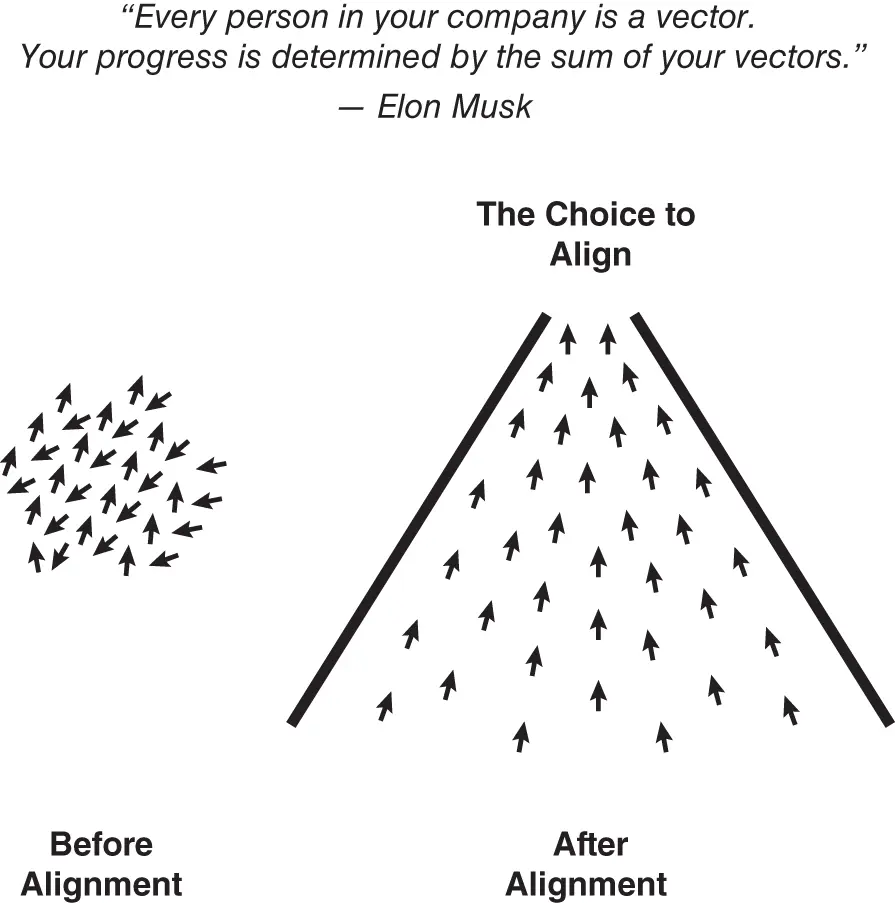

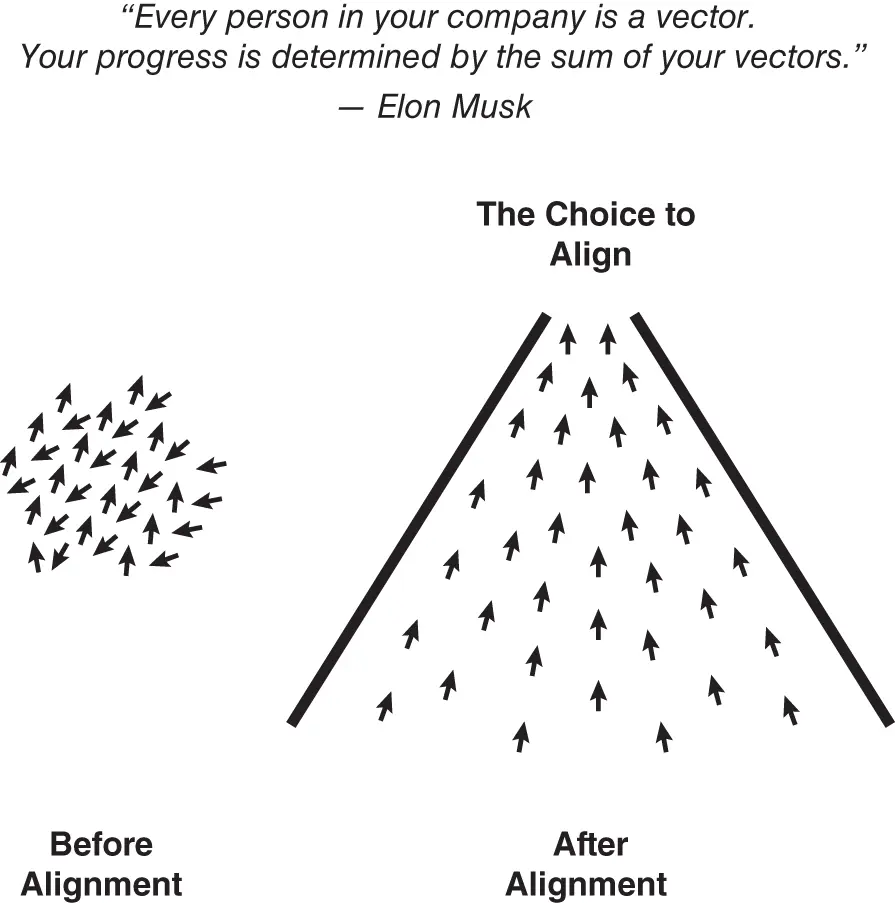

FIGURE 1.1 The Art of Aligning People as Vectors

Alignmentoccurs in a social system, like a team or company, when the individuals come together and adopt shared ways of working toward a common goal. It is not necessary for each person to agree, but they must choose to align out of a recognition that it is for the common good of the team or organization.

To achieve alignment in a complex adaptive social system, leaders must become skilled at breaking complex issues down to the key choice points. These are the moments when people need to consciously choose to come along on the journey together, and the leader's job is to initiate the conversations that lead to those choices. These are the seven “crucial conversations” that we will delve into more deeply in the third section of this book. They are an essential part of the Growth River Operating System. Out of these conversations, people can come to a choice about what's right for the team and decide upon and implement shared ways of working. There is no subterfuge or sleight of hand involved in obtaining alignment. That would defeat the purpose. These are conversations that are held transparently and openly. Suffice to say again that we're not talking about requiring every individual to perfectly agree with or even like the decisions that are made, but we are talking about every individual recognizing those decisions to be in the best interests of the team or organization. Therefore, they'll choose to put that above their own preferences or opinions.

Unless a leader respects people's agency, and skillfully creates the choice points at which they can align, the result will never be transformation in the team or organization. But this way of thinking is counterintuitive. People often think that they can grow faster if they drive choice out of the system. When you're caught in the Swirl, the last thing you feel like doing is inviting more input, opinions, and perspectives into the conversation. That brings about a level of complexity that some leaders find unbearable. They want to “nail and scale” their business models and their systems, so that they run like a well-oiled machine. It may even work for a period of time, so long as the waters are calm and the currents predictable. It may even be appropriate at certain points in the organization's journey. But here's the issue. Without knowing it, they have created a culture with so little tolerance for diversity that it can't handle complexity. As soon as they hit a certain level of complexity, or unexpected events throw them off balance, it becomes difficult to function. By driving choice and agency out of the system for all but the top leadership, they have lowered their own potential as an organization to adapt, to be creative, to pivot, and ultimately to grow and thrive over the long term. If you want to get out of the Swirl, you don't do so by shutting down the conversation; you do so by accelerating the clarity of the conversation, which means getting to alignment.

That is what the Growth River Operating System allows you to do—create alignment and lead transformation in complex adaptive social systems. “Operating System” may sound like it's straight out of the old machine metaphor I've just advised you to leave behind. But it's not software I'm talking about; it's “social-ware.” social-ware means a system for working together in a social system that enables higher performance. It is an upgrade for the human system in the same way that software can be an upgrade for a computer system. Again, it's not simple, because human systems are not simple. It's not a quick fix, because adaptation and evolution doesn't happen quickly. But it is elegant, creative, uplifting, and powerful, because at their best, human systems are all of those things.

CHAPTER 2 Understanding Businesses: The Business Triangle

If you can't describe what you're doing as a process, you don't know what you are doing .

—W. Edwards Deming

What is a business? And what does it mean to be in business together?

Sometimes in workshops, I lead a simple exercise: I ask people to jot down on a piece of paper their best definition of a business. It's revealing. The answers that people give tend to be strongly influenced by the roles that they play in the company. So, for example, a marketing person might say “a business is a system for winning in the marketplace,” whereas a product designer might say “a business is an engine for innovation.” People naturally tend to be focused on the deliverables, metrics, and priorities that are their responsibilities. As a result, to borrow an oft-used phrase coined by Michael Gerber, they're used to working in the business but they're unable to work on the business —because they can't even see the business as a whole. Too often, team members don't have a clear picture of the relationships between different aspects of the business and the way they all fit together. In their minds, it is as if the organization is just a big collection of people with different jobs, all working alongside each other—a giant blob of activity and intersecting objectives.

That's not really a helpful way to think. Organizations may be social systems, but in a business context, they're more than just communities of people. A business organization exists for a purpose: to create value for customers . That's what connects the people in the organization and the activities they enact. But when I ask people to describe that overall value creation process—the shared work they are in together with their team and their organization—too often, they come up short. If the people working in a business do not have a shared definition and model of what a business is, is it any wonder that they struggle to align as they go about doing their jobs?

Unless we can visualize our shared work, it is inevitable that we will fall into difficult decision-making, unhelpful politics, unclear roles, redundancies, and inefficiencies. And unless we have a common way to understand the business we're in, we can't work on, improve, optimize, and grow that business together.

The Importance of Visualizing Shared Work

If you work in a manufacturing context—in a production line, for example—it may not be that difficult to visualize the shared work of the team or company. You may be responsible for just one step in the process, but the production line itself is a physical representation of all the stages through which the work flows, and the order in which it must be enacted. You wouldn't try to pick up a widget from one end of the assembly line and move it somewhere else, and you're not worried that someone further down the line is going to start trying to do your job.

These days, however, most people don't work in production lines. In today's flat digital work world, most of us are “ knowledge workers, ” a term coined in 1959 by business writer and consultant Peter Drucker to refer to any person whose job involves handling or using information. According to research firm Gartner, there are now more than a billion knowledge workers globally. 1 And the core challenge for the knowledge worker is finding a way to optimize and streamline their shared work when the processes and products of that work are no longer physical objects being moved from one place to another. So much confusion in organizations comes down to these issues. Things fall through the cracks because no one feels responsible for them. Two people realize they're both doing the same thing. This person isn't talking to that person. No one knows who has the authority to make certain decisions. Or too many people have the authority to make certain decisions. Leaders try to move people around or redesign their org charts to fix these problems, but they don't really drill down to see the system or process that underlie those human roles, responsibilities, and relationships. That system is the business, and unless we get clarity on the business, our best attempts to organize around it will still be scattershot. As Drucker pointed out, in order to be productive and effective, teams engaged in knowledge work must invest the time and resources to visualize shared processes and ways of working, because how else will they be able to easily plan, start, stop, track, troubleshoot, and optimize shared work together?

Читать дальше