This ‘MAE’ accent, equally dubbed ‘Transatlantic’ accent, used to be very popular from the 1920s/1930s to the end of World War II (MacNeil & Cran, 2005, p. 51). Yet, its overall usage was clearly beginning to wane following World War Two. The British expatriate Angela Lansbury, for example, who moved to New York in 1940 and is well known for having played the part of a bestselling crime author and amateur detective Jessica Fletcher in the television series Murder, She Wrote, exemplified this ‘MAE’ accent.

Still, this empirical project embraces the linguistic concept that is based on Modiano’s definition of ‘MAE’: “Recent findings suggest, however, that an increasing number of native speakers are mixing features of AmE and BrE, and furthermore, many, if not most second language speakers in Europe and elsewhere have begun to speak a mixture, sometimes called Mid-Atlantic English” (Modiano, 1996a, p. 5).

The following briefly outlines some scholars’ vision of ‘MAE’ as a linguistic concept.

Görlach and Schröder stated that the concept of ‘MAE’ is an insufficient ‘variety’ of English: “an odd mixture of speech levels and…an artificial jargon, which is acceptable neither to the educated Briton nor to the educated American” (1985, p. 230). Axelsson (as cited in Modiano, 2002, p. 133) argues in a less critical manner by claiming that “Mid-Atlantic English, at least in the sense Modiano uses it in his 1993 article, is still a utopian variety of English not yet established in Sweden, even if the general development seems to be slowly moving in that direction”. Her position is based on her study of Swedish university students’ pronunciation patterns. It brought to light that 70 % of the students mixed features of BrE and AmE, as the recordings revealed (Modiano, 2002, p. 144). Furthermore, she dismisses the label of ‘Mid-Atlantic English’ on the grounds that ‘mid’ would suggest equal influence from both major varieties. Another reason she provides against this term is that it would “exclude all varieties used in other parts of the globe than those close to the Atlantic Ocean” (Modiano, 2002, p. 133).

These two stances on the notion of ‘MAE’ contrast with Modiano’s vision of the current role of English. He envisages a “consumer-friendlier” educational system through the removal of BrE from its unique unchallenged position and advocates increased appreciation of the AmE variety of English, which is gaining in importance due to the effects of the ongoing linguistic and cultural process of Americanisation.

The process of Americanisation that learners of English are undergoing will bring about a shift in their English-language usage: they will be mixing BrE and AmE at the four levels of lexis, pronunciation, lexico-grammar and spelling. This convergence of the two main varieties is labelled by Modiano as ‘MAE’. He argues that ‘MAE’ not only entails a mixture of BrE and AmE but most importantly describes a strategy to “benefit the communicative act” (Modiano, 2009, p. 61). He posits that for EFL speakers, English is used for utilitarian purposes to fit in with a cross-cultural context of speakers of diverse L1 backgrounds. Modiano further argues that in the wake of the impact of AmE on EFL speakers, the first stage of this language change will be the ‘MAE’ conceptualisation of English and the second the emergence of Euro-English, used as a second language. As a consequence, he firmly opposes the view that mainland Europeans’ L2 usage of English will perpetuate the status quo of a foreign language (Modiano 2009, 2017).

Melchers, however, provides a definition of ‘MAE’ with the sole focus on its phonological features, although evading the term ‘variety’:

Mid-Atlantic–in its general sense–refers to something which has both British and American characteristics, or is designed to appeal to both the British and the Americans…a term for kinds of English, especially accents, that have features drawn from both North AmE and BrE. (1998, p. 263)

Regarding the influence of AmE on International English 1, the homogenisation in terms of lexis, for instance, towards an increasing usage of AmE, was substantiated by Trudgill (as cited in Jenkins, 2003, p. 91), who asserts that “the general trend does seem to be towards increasingly international use of originally American vocabulary items”. As claimed by him, the reason for this lies in people’s high exposure to the media and film industries dominated by the US. This ‘MAE’ usage was corroborated by a Swedish study carried out by Söderberg and Modiano in 2002 (Modiano, 2002, pp. 147–171). It evidenced that Swedish schoolchildren had a clear bias towards AmE lexis. Crystal also subscribes−albeit in a more general sense−to Trudgill’s view by asserting “US English does seem likely to be the most influential in the development of WSSE” 2(Crystal, 2003a, p. 188). Concerning linguistic Americanisation, Engel boldly imagines that “[…] 2120 would be a plausible and arithmetically neat guesstimate−when American English absorbs the British version completely” (Engel, 2017, p. 3).

Against this backdrop, the question arises whether it is pedagogically sound to advise EFL learners against using a mixture of BrE and AmE. The following chapter will therefore discuss the issue of consistency between BrE and AmE in EFL settings.

2.2 The Issue of Consistency

The issue of consistency, i. e. a consistent usage of either BrE or AmE is inextricably linked with the notion of ‘MAE’ (Modiano, 2009, p. 96). It is fair to acknowledge that the increasing influence of AmE on students’ English makes a pure rendition of BrE impossible. The sociolinguistic fact is that not only do learners of English mix features of BrE and AmE, but also a substantial number of native speakers of English (cf. Modiano, 1996a, p. 5), which is why I resolved not only to take three informant groups of NNSs in the EFL context but also UK NSs of English as an important reference group.

Modiano strongly advocates a conscious mix of BrE and AmE by positing that “a good communicator strives to use features of the language which are most easily understood by the interlocutor, and if this means that one mixes features of various varieties, this should be both accepted and encouraged” (Modiano, 2009, p. 96). The scholar also believes that the call for consistency is often just a “disguised form of discrimination” (Modiano, 1998, p. 242).

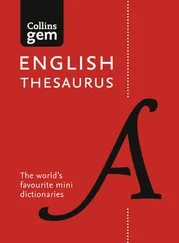

However, as far as the implications for the EFL educational context are concerned, it may be objected that an erratic mixing of BrE and AmE ought to be discouraged. A mixed usage of BrE and AmE spelling items, for instance, could strike the reader as disturbing and confusing. This also holds true for the lexical area. While EFL learners’ developed ability to adapt to the communicative situation at hand eases communication in global exchanges, at the same time it also demands from them to maintain some degree of consistency to avoid random mixing, which would be counterproductive in terms of communicative expediency.

The following recommendation for EFL teaching could therefore be considered: only mix when indispensably necessary for the purposes of situational adaptation and definitely refrain from using culture-specific lexis. 3A case in point for culturally-induced “lexical specificity” is the BrE term ‘public school’, which may give rise to misunderstandings in international settings. In the UK, this type of school denotes a privately-owned institution. Parents pay for their children’s education there. The AmE equivalent ‘private school’ is understood internationally as fee-paying educational establishments. Conversely, the AmE ‘busboy’ might be confusing to an EFL speaker and linguistically not adapted to international forums. In AmE, it denotes a person who works in a restaurant whose task is to remove dirty dishes and bring clean ones. A ‘waiter’s assistant’ would be the more communicatively expedient term for international settings. Hence, awareness-raising of BrE and AmE contrasts in the four language areas of lexis, pronunciation, lexico-grammar and spelling urgently needs to be placed high on the agenda in terms of innovative teaching and learning protocols. In this manner, EFL learners are better equipped to decide in which sociolinguistic circumstances the variety switching may be an extremely efficient cross-cultural communicative tool. Accordingly, it was also the objective of the present investigation to elicit the surveyed informants’ stance on a consistent use of either BrE or AmE. The demand for consistency was indeed no longer supported by large segments of EFL survey populations in Sweden, for example. They turned out to be keen mixers of the two major forms of English (Modiano, 2002, 2009).

Читать дальше