It is important to acknowledge that no equivalency existed between indigenous land-use practices and European ones. Whether the numerous different indigenous cultures living in the space of the borderland used intercommoning techniques, shared natural resource commons, or sustained traditions of taking based on possession, labor or justified use, matters little to an understanding of how European agriculture served colonization. Colonizers hailed from a limited area, brought with them a fairly unified set of practices, and shared similar aims. Their history is generalizable. Indigenous cultures adapted their extractive methods over generations to very specific places and with diverse goals. Drawing comparisons between indigenous and settler commons, except at the broadest sociopolitical level, does these cultures an injustice and suggests false equivalencies and “both-sides-ism.” Labeling Indigenous Peoples “commoners all,” and exporting the Anglo-French channel community’s commons culture to a global analysis flies in the face of indigenous sovereignties (Linebaugh 2008). Grasping the historical meaning of the commons is challenging enough without obscuring its significance with false comparisons. What can be stated with assurance is that for Indigenous Peoples experiencing colonization, the outer commons was a place of exchange, learning, conflict, and loss.

The discussion in this chapter demonstrates how a subaltern agricultural knowledge system transferred to North America transformed in the sociopolitical dynamics of colonialism. Its transformation into the means of indigenous dispossession and land theft, while partly serendipitous and partly intentional, was only possible because of the larger imperialist structures that enabled Europeans to dominate: disease, metropolitan industrialization, global trade networks, and overweening demographics. There was another kind of transfer in colonialism, of indigenous “knowledge systems,” the understanding of which historian Judith Carney argues in the case of rice cultivation, are key to revealing the “agrarian genealogy” of agricultural practices central to the success of colonialism (Carney 2001). This section of this chapter surveys a broad swath of the work exploring these forced knowledge transfers.

Some scholars have missed a significant step in the evolution of colonial agriculture by failing to highlight colonizers’ extractions of this wisdom, know-how, or metis, to identify, cultivate, and produce agricultural commodities. Certainly the many agricultural commodities, whose origins lay in the deep past of indigenous time, mattered to the successes of colonialism. The seductive and coercive regimes instituted to produce them also mattered. The labor of brown people to serve white agendas is also obviously important. Yet, knowledge and know-how are equally significant. In fact, whether transported to colonial North America as in the case of the know-how to cultivate rice, sugar, and marijuana, or expropriated in the colonies such as methods of planting and harvesting tobacco, henequen and sisal fiber, potatoes, and chocolate, forced knowledge transfers were a key part of what made colonial agriculture productive and successful. Marcy Norton persuasively argues that seeing such commodities as “technologies … usefully concretize[s their] analytic utility” (Norton 2017). Colonial agricultural commodities were more than products, they represented ways of knowing and doing, which were almost wholly locked away in indigenous minds.

The sociopolitical dynamics of the commons also applied to the extractions of indigenous technological, geographical, and meteorological knowledge systems, which occurred in the colonial outer commons. Making this distinction is important, for the implicit line dividing inner and outer commons, became a clear color line in knowledge expropriation. Rather than being a passive boundary violation of indigenous space by means of grazing, disease, or the spread of invasive cultivars, forced knowledge transfers required the active discernment and theft of Indigenous knowledge. Colonizers appreciated indigenous agricultural commodities and methods, and understood the potential they represented for wealth creation, if they could take and control them, and plug them into global mercantile trade networks. For example, the “Irish” potato, domesticated in the Andes over 8000 years ago, underwent colonial expropriation, was taken to Europe in the mid-1500s, then reintroduced to the North American colonies early in the eighteenth century, and quickly became a staple in colonists’ diets (Smith 2011). The means of justifying these takings was based on division represented by colonial insider and colonized outsider, including the common belief that indigenous and African people were incapable of truly utilizing their own knowledge properly. The final step in this knowledge extraction, was to replace the indigenous origins of agricultural knowledge with their own “better” (read: proper, more efficient, and profitable) uses of such knowledge, thereby erasing the distinction between inner and outer commons, and effectuating a conquest of more than territory.

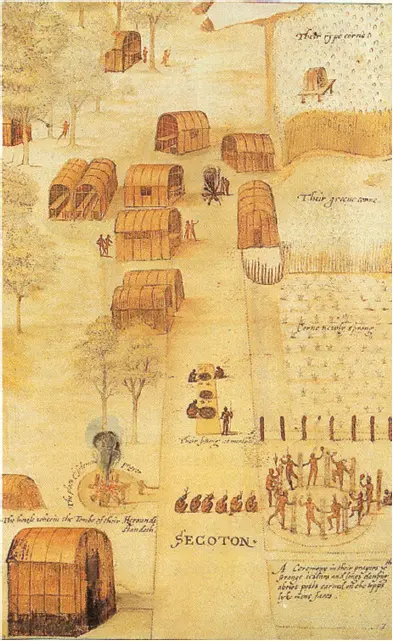

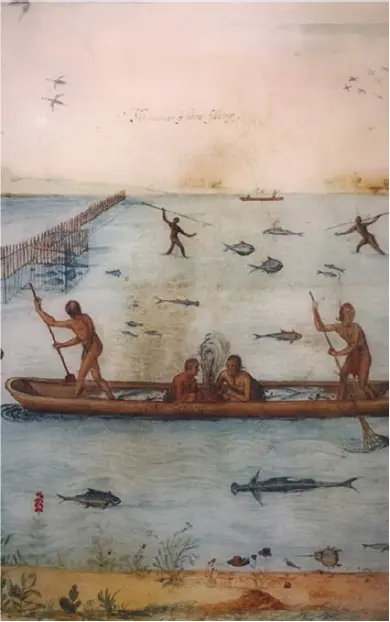

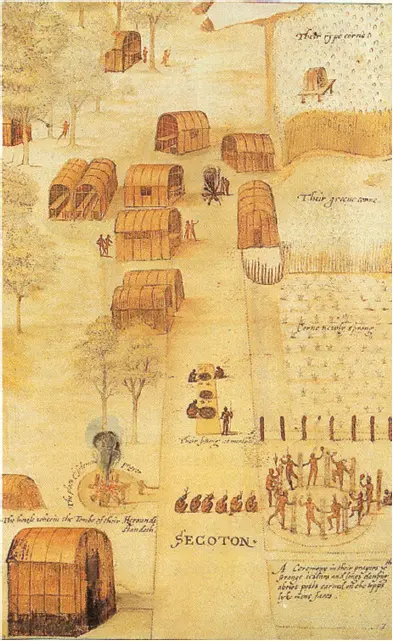

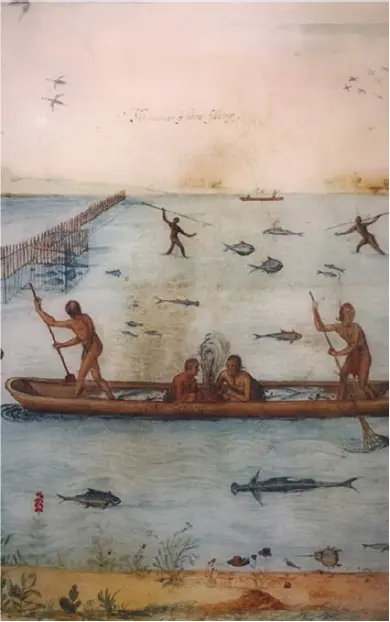

One of the earliest visual records of North American indigenous agricultural skill were the watercolors John White, created as part of Sir Walter Raleigh’s Roanoke expedition in 1585 (Oberg 2010). His bird’s eye view of the Algonquian village of Secoton (Figure 2.1) reveals orderly rows of corn planted in rotation from “corne newly sprung,” to “their greene corne,” and then to “their rype corne.” In Secoton, a boy perches in a raised shelter to discourage birds from eating the corn while it dries, and nearby a neatly staged hulling area testifies to the care these American farmers took in harvesting and preserving this valuable source of nutrition. Another painting (Figure 2.2) depicts the diversity of aquatic life available to harvest, but also the techniques Algonquians used to harvest and preserve their catch, including the use of an elaborate weir. Fish weirs were of course not exclusively an indigenous American technology, but this image does demonstrate an organizational system for resource extraction, which gives the lie to many colonizer descriptions of “nomadic bands,” “scattered tribes,” and rootless wanderers. Abundant evidence can be found that Indigenous Americans both husbanded game and extracted it conservatively, something which became apparent as colonizer markets promoted over-extraction (Morrissey 2015).

Figure 2.1 Secoton, an Algonquian village, watercolor by John White during Sir Walter Raleigh’s Roanoke expedition in 1585. John White/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain.

Figure 2.2 Algonquian fish harvesting, watercolor by John White during Sir Walter Raleigh’s Roanoke expedition in 1585. John White illustration of Algonquian fishing techniques, 1585/National Park Service.

Successive cropping demonstrates a high level of stability in the agricultural cycle, which counters long-standing myths—now debunked—of widespread use of swidden (slash and burn) requiring regular field rotation due to soil depletion (Doolittle 2000). Jane Mt. Pleasant (2015), building on the work of William E. Doolittle, argues that Native American agriculturalists “practiced what today is called conservation tillage, which minimizes or eliminates plow tillage.” Instead, Native farmers used the hand trowel to cultivate the soil, minimizing the depletion of the valuable yet fragile alluvial soils (Inceptisols). This technique enabled successive plantings in the same location without exhausting the soil. Indigenous agricultural techniques were highly productive. In the 1680s, the Governor of New France destroyed more than a million bushels (42,000 tons) of corn from just four Haudenosaunee villages (Mann 2005, quoted in Dunbar-Ortiz 2014). “Today,” Mt. Pleasant reminds us, “growing crops without plows is a primary characteristic of environmentally sustainable farming” (Mt. Pleasant 2015). As Jennifer Anderson has explored for the Algonquian farmers of Long Island, when fields became depleted, indigenous farmers most likely did use fish fertilizer, a practice the New English readily adopted (J. Anderson 2015).

Читать дальше