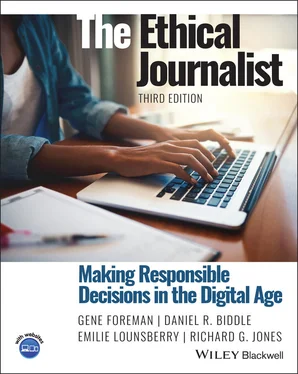

Gene Foreman - The Ethical Journalist

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gene Foreman - The Ethical Journalist» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Ethical Journalist

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ethical Journalist: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Ethical Journalist»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Praise for the Third Edition of The Ethical Journalist

ANN MARIE LIPINSKI,

Praise for the Earlier Editions

GENE ROBERTS,

ALICIA C. SHEPARD, The Ethical Journalist

The Ethical Journalist

The Ethical Journalist — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Ethical Journalist», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Svart’s death came three months after her doctor informed her she would die of lung cancer within six months. The former research librarian disclosed the grim prognosis to a reporter friend at The Oregonian in Portland, the newspaper where she had worked. She said she had decided to avail herself of Oregon’s assisted‐suicide law. Svart also said she wanted to talk to people frankly about death and dying, hoping she could help them come to grips with the subject themselves. Out of that conversation grew an extraordinary mutual decision: On its website and in print, The Oregonian would chronicle Lovelle Svart’s final months on earth.

In her series of tasteful “video diaries,” she talked about living with a fatal disease and about her dwindling reservoir of time. In response, hundreds of people messaged her on the website, addressing her as if they were old friends.

But before Svart taped her diaries, journalists at The Oregonian talked earnestly about what they were considering. Most of all, they asked themselves questions about ethics.

The threshold question was whether their actions might influence what Svart did. It is not unusual for journalists to worry about doing something that could change the story they are covering. In this case, however, the stakes could not be higher. Would Svart feel free to change her mind? After all the attention, would she feel obligated to go ahead and take the lethal dose? On this topic, the Oregonian journalists were comforted by their relationship to their story subject. Familiarity was reassuring, although in the abstract they would have preferred to be reporting on someone who had never been involved with the paper. In 20 years of working with her, they knew Svart was strong‐willed; nobody would tell her what to do. Even so, the journalists constantly reminded her that whatever she decided would be fine with them. Michael Arrieta‐Walden, a project leader, personally sat down with her and made that clear. The story would be about death and dying, not about Svart’s assisted suicide.

Would the video diaries make a statement in favor of the controversial state law? No, they decided. The debate was over; the law had been enacted and it had passed court tests. Irrespective of how they and members of The Oregonian’s audience felt about assisted suicide, they would just be showing how the law actually worked – a journalistic purpose. They posted links to stories they had done earlier reflecting different points of view about the law itself. Other links guided readers to organizations that supported people in time of grief.

In debates among themselves and in teleconferences with an ethicist, they raised other questions and tried to arrive at answers that met the test of their collective conscience. For example, a question that caused much soul‐searching was what to do if Svart collapsed while they were alone with her. It was a fact that she had posted “do not resuscitate” signs in her bedroom and always carried a document stating her wishes. Still, this possibility made them very uncomfortable – they were journalists, not doctors. Finally they resolved that, if they were alone with her in her bedroom and she lost consciousness, they would pull the emergency cord and let medical personnel handle the situation. As Svart’s health declined, they made another decision: They would not go alone with her outside the assisted‐living center where she lived. From then on, if they accompanied her outside, there would also be another person along, someone who clearly had the duty of looking out for Svart’s interests. 2

The self‐questioning in the Oregonian newsroom illustrates ethics awareness in contemporary journalism. “Twenty years ago, an ethical question might come up when someone walked into the editor’s office at the last minute,” said Sandra Rowe, then the editor of The Oregonian . “We’ve gone through a culture change. Now an ethical question comes up once or twice a week at our daily news meeting, where everyone can join the discussion. We are confident we can reach a sound decision if everyone has a say.” 3

Incentives for Ethical Behavior

Most journalists see theirs as a noble profession serving the public interest. They want to behave ethically.

Why should journalists practice sound ethics? If you ask that question in a crowd of journalists, you will probably get as many answers as there are people in the room. But, while the answers may vary, their essence can be distilled into two broad categories. One, logically enough, is moral; the other could be called practical.

The moral incentive

Journalists should be ethical because they, like most other human beings, want to see themselves as decent and honest. It is natural to crave self‐esteem, not to mention the respect of others. There is a psychic reward in knowing that you have tried to do the right thing. As much as they like getting a good story, journalists don’t want to be known for having exploited someone in the process.

The practical incentive

In the long term, ethical journalism promotes the news organization’s credibility and thus its acceptance by the public. This translates into commercial success. What journalists have to sell is the news – and if the public does not believe their reporting, they have nothing to sell. Consumers of the news are more likely to believe journalists’ reporting if they see the journalists as ethical in the way they treat the public and the subjects of news coverage. Just as a wise consumer would choose a product with a respected brand name over a no‐name alternative when seeking quality, journalists hope that consumers will choose their news organization because it behaves responsibly – because it can be trusted.

Why Standards Are Needed

There are also practical arguments for ethical behavior that flow from journalism’s special role in American life.

The First Amendment guarantee of a free press means that, unlike other professionals, such as those in medicine and the law, journalists are not regulated by the state and are not subject to an enforceable ethics code. And that is a good thing, of course. The First Amendment insulates journalists from retribution from office holders who want to control the flow of information to the public and who often resent the way they are covered in the media. If a state board licensed journalists, it is a safe bet that some members of the board would abuse their power to rid themselves of journalists who offend them. The public would be the loser if journalists could be expelled from the profession by their adversaries in government.

But there is a downside to press freedom: Anybody, no matter how unqualified or unscrupulous, can become a journalist. It is a tolerable downside, given the immense benefit of independent news media. Nevertheless, bad journalists taint the reputation of everyone in the profession. Because they are not subject to legally enforceable standards, honest journalists have an individual obligation to adhere voluntarily to high standards of professional conduct. Ethical journalists do not use the Constitution’s protection to be socially destructive.

Yet another argument for sound ethics is the dual nature of a news organization. Journalism serves the public by providing reliable information that people need to make governing decisions about their community, state, and nation. This is a news organization’s quasi ‐ civic function. But the news organization has another responsibility, too – and that is to survive in the marketplace. Like any other business, the newspaper, broadcast station, or digital news site must earn an income.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Ethical Journalist»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Ethical Journalist» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Ethical Journalist» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.