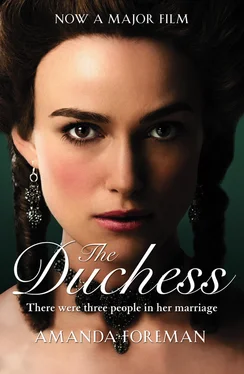

The Duchess

GEORGIANA:

DUCHESS OF DEVONSHIRE

AMANDA FOREMAN

Cover

Title Page The Duchess GEORGIANA: DUCHESS OF DEVONSHIRE AMANDA FOREMAN

Introduction

Family Trees

Part One: Débutante

1 Debutante: 1757–1774

2 Fashion’s Favourite: 1774–1776

3 The Vortex of Dissipation: 1776–1778

4 A Popular Patriot: 1778–1781

5 Introduction to Politics: 1780–1782

Part Two: Politics

6 The Cuckoo Bird: 1782–1783

7 An Unstable Coalition: 1783

8 A Birth and a Death: 1783–1784

9 The Westminster Election: 1784

10 Opposition: 1784–1786

11 Queen Bess: 1787

12 Ménage à Trois: 1788

13 The Regency Crisis: 1788–1789

Part Three: Exile

14 The Approaching Storm: 1789–1790

15 Exposure: 1790–1791

16 Exile: 1791–1793

17 Return: 1794–1796

18 Interlude: 1796

19 Isolation: 1796–1799

Part Four: Georgiana Redux

20 Georgiana Redux: 1800–1801

21 Peace: 1801–1802

22 Power Struggles: 1802–1803

23 The Doyenne of the Whig Party: 1803–1804

24 ‘The Ministry of All the Talents’: 1804–1806

Epilogue

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Biographers are notorious for falling in love with their subjects. It is the literary equivalent of the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’, the phenomenon which leads hostages to feel sympathetic towards their captors. The biographer is, in a sense, a willing hostage, held captive for so long that he becomes hopelessly enthralled.

There are obvious, intellectual motives which drive a writer to spend years, and sometimes decades, researching the life of a person long vanished, but they often mask a less clear although equally powerful compulsion. Most biographers identify with their subjects. It can be unconscious and no more substantial than a shadow flitting across the page. At other times identification plays so central a role that the work becomes part autobiography as, famously, in Richard Holmes’s Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer (1995).

In either case, once he commits himself to the task, the writer embarks on a journey that has no obvious route for a destination that is only partly known. He immerses himself in his subject’s life. The recorded impressions of contemporaries are read and re-read; letters, diaries, hastily scribbled notes, even discarded fragments are scrutinized for clues; and yet the truth remains maddeningly elusive. The subject’s own self-deception, mistaken recollections, and the hidden motives of witnesses conspire to make a complete picture impossible to assemble. Finally, it is intuition and a sympathy with the past which supply the last missing pieces. It is no wonder that biographers often confess to dreaming about their subjects. I remember the first time Georgiana appeared to me: I dreamt I switched on the radio and heard her reciting one of her poems. That was the closest she ever came to me; in later dreams she was always a vanishing figure, present but beyond my reach.

Such profound bonds have obvious dangers, not least in the disruption they can inflict upon a biographer’s life. Sometimes the work suffers; its integrity becomes jeopardised when, without realising it, a biographer mistakes his own feelings for the subject’s, ascribing characteristics that did not exist and motives that were never there. In his life of Charles James Fox, the Victorian historian George Trevelyan insisted that Fox held to a strict code of morality regarding the sexual conquest of aristocratic women; he only seduced courtesans. Trevelyan, perhaps, had such a code, but Fox did not. There is ample evidence to suggest that the Whig politician had several affairs with married women of quality, including Mrs Crewe and possibly Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Her first biographer, Iris Palmer, was similarly wishful in her description of Georgiana as a ‘simple woman’ without ambition except in her desire to help others. Palmer also claimed, in the face of contrary evidence, that Georgiana was only unfaithful to her husband with one man, Charles Grey. Both biographers illustrate how easy it is to fall prey to the temptation to suppress or ignore unwelcome evidence.

Fortunately, the emotional distance required to construct a narrative from an incoherent collection of facts and suppositions provides a powerful counterbalance. By deciding which pieces of the puzzle are the most significant – not always an easy task – and thereby asserting their own interpretation, the biographer achieves a measure of separation. The demands of writing, of style, pace and clarity, also force a writer to be more objective. Numerous decisions have to be made about conflicting evidence, or where to place the correct emphasis between certain events. Having previously dominated the biographer’s waking and sleeping life, the subject gradually diminishes until he or she is contained on the page.

I discovered Georgiana in 1993, while researching a doctoral dissertation on English attitudes to race and colour in the late eighteenth century. I was reading a biography of Charles Grey, later Earl Grey, by E. A. Smith, and came across one of her letters. I was already familiar with Georgiana’s career as a political hostess and as the duchess who once campaigned for Charles James Fox, but I had never read any of her writing, and knew little of her character. I was struck by her voice, it was so strong, so clear, honest and open, that she made everything I subsequently read seem dull by comparison. I lost interest in my doctorate, and after six months I had read just one book on eighteenth-century racial attitudes. Whenever I did go to the library it was to look for biographies of Georgiana.

There have been three previous biographies about her, all of them remarkably similar. Iris Palmer’s The Face without a Frown , written in 1944, was a novelization of Georgiana’s early life. It made no claim to be a historical biography, although Palmer did quote from Georgiana’s letters. The other two, The Two Duchesses , by Arthur Calder-Marshall (1978), and Georgiana , by Brian Masters (1981), also concentrated on her early life. Both Calder-Marshall and Masters were probably influenced by the edited selection of Georgiana’s letters, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire , published by the Earl of Bessborough in 1955. (It was only much later that I discovered the extent of Lord Bessborough’s editing for myself.) None of the books, not even the Bessborough edition of her letters, portrayed the Georgiana whose voice I felt I had heard. Eventually I realized I would never be satisfied until I had followed the trail to its source. Oxford accepted my explanation and graciously allowed me to start again and begin a new D.Phil, on Georgiana’s life and times. A short while later I decided to write her biography in addition to the doctorate.

As Georgiana’s letters are scattered around the country, I planned to be on the road for eighteen months and set off in the summer of 1994, having finally passed my driving test on the seventh attempt. My fears about starting a new project were subsumed by the act of driving on the motorway for the first time. I began my search at Chatsworth in Derbyshire, Georgiana’s home during her married life. Its archives, hidden away inside a subterranean labyrinth of corridors, contain over 1,000 of her letters. They revealed so much of her daily life that it seemed as though I were watching a play from the corner of the stage. The impression of being an invisible, perhaps even an uninvited, spectator remained with me throughout my research.

Читать дальше